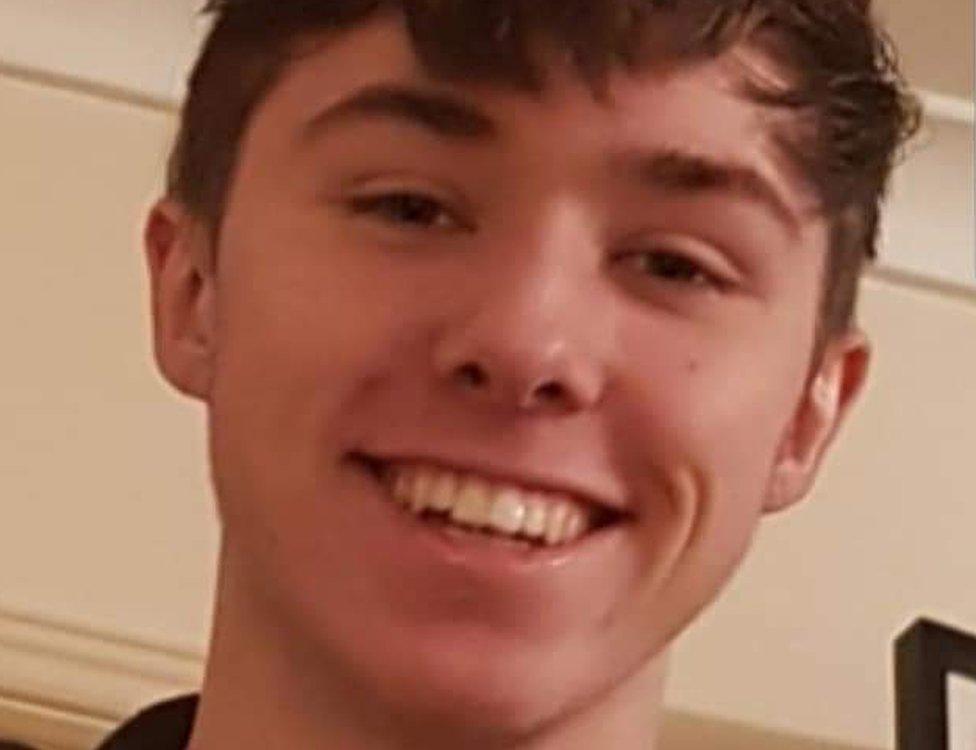

Lewis McCracken: Father says lockdown may have played part in son's suicide

- Published

Lewis McCracken took his own life on 30 April 2020, six weeks into the first lockdown

"He was just a normal 17-year-old kid, we don't understand what happened."

Two years on from the shock of his son's suicide, Ian McCracken still has no real explanation for why the popular Belfast schoolboy took his own life.

But because of the timing of Lewis McCracken's death, six weeks into the first wave of Covid-19, his father has long suspected lockdown played a part.

Ahead of the second anniversary of his death, he has shared their story in a bid to encourage other young people to talk about their problems and seek help.

"Were there signs? No. If there were, we didn't see them," Mr McCracken told BBC's Good Morning Ulster.

"He was making plans for the future. He was on a Google classroom that day. He was telling me: 'Dad, we need to buy books for the summer so I can revise.'"

Ian McCracken talks about his son's suicide

When the pandemic began, Lewis was in the first year of his A-Level studies and appeared to be an average teenager with typical teenage preoccupations.

He really loved computer games; he played guitar; he had a part-time job.

He had recently passed his driving test and was enjoying a new-found sense of independence.

A few months earlier, he had moved schools to Campbell College in east Belfast, but he had made new friends there and liked the "social side of school" more than the academic side, according to his father.

Lewis pictured in his school uniform with his dad, Ian McCracken

When asked to describe his son, the words that come to mind are "mischievous" and "impulsive" because Lewis frequently got into trouble in class.

"You got to know his headmasters and his teachers very well because you were always getting phone calls to come and explain," his father laughs.

So when the UK government ordered a strict nationwide lockdown from 23 March 2020, Lewis was initially delighted.

"At first he thought this was great because he was going to be on Netflix full time, he was going to be doing his games because he was a gamer, and he thought life couldn't get any better," Mr McCracken says.

'Bored and lonely'

Schoolwork somewhat "spoilt" the party though as Lewis had to take part in several remote learning lessons per day, which he found tough at the start.

However, as the weeks passed, his father noticed that the novelty had quickly worn off.

"He started getting bored with full-time Netflix and full-time gaming.

"He started saying things like: 'I'm bored and lonely.'"

Lewis loved socialising with his friends both on and offline

Lewis no longer had his part-time job and could not meet his friends in person.

But if this was a cry for help, Mr McCracken says he did not recognise it as everyone was experiencing similar feelings by that stage of lockdown.

"Bored and lonely didn't do it for me, it didn't worry me," he says.

"You passed his bedroom and you'd have thought there was a dozen people in it because he was online playing games and you could hear all his friends talking and shouting and screaming."

On the evening before he took his own life in the garage of their family home, Lewis was still giving nothing away.

He asked his father for money so he and a friend could watch a film on an online streaming service.

'You don't expect it to be the last time you see him'

The day after his death, Mr McCracken says he asked himself the question: "What the hell did he watch?"

"But it was actually a funny film called Eddie the Eagle," he recalls, just another commonplace detail that provided no clues as to what would happen next.

The pair had spent the whole of lockdown alone together at home as both father and son and "kind of house buddies" and their final words were ones of warm affection.

"You put your head round his door and you say: 'Good night Lewis, love you,' and he says: 'Love you' back," Mr McCracken recalls.

"You don't expect that to be the last time you see him."

Ian McCracken and his son Lewis in their younger days

Lewis took his own life on 30 April 2020, and his family have been left with endless unanswered questions.

"The police took away his phone and his computer and all that stuff. The coroner gets involved, it takes months and months to come to a conclusion," his father explains.

"And then you worry, because he was young and you were allowing him to have a beer - did he have too many beers that day and did he not know what he was doing?

"It took six months to find out that yes, he had some alcohol in his system, but it was less than the legal limit to drive so he knew what he was doing. So this was something that he wanted to do."

Like most families who lost loved ones during Covid lockdowns, the McCrackens were not allowed to hold a traditional funeral service.

A large crowd of Lewis' friends and family waited outside their home and walked behind the hearse to the crematorium, but they were stopped and spoken to by a passing police patrol because that was against the rules at the time.

In the immediate aftermath, and even now, Mr McCracken suspects the enforced isolation of lockdown may have contributed to his son's suicide.

'Ask for help, that's the main thing'

"We're never going to know that, but I believe that it must have had a part in it," he says.

"I think he enjoyed being with his friends, the social side of school."

However, he admits that even if someone had told him during lockdown that his bright, mischievous and popular son was suicidal, he would have struggled to believe them.

"Maybe he was telling us he was having trouble when he said: 'I'm bored and lonely'. But, we were locked in the house and we were all kind of bored and lonely so if that was him asking for help, you need to really ask for help," he says.

There was a Facebook post doing the rounds at the time offering support for people who were feeling suicidal, pointing out that it was one of the biggest causes of death among young men.

"Two people had tagged Lewis two weeks before he took his own life in that sort of message. He never responded to it.

"Is that a sign? I don't know, but you only find these things afterwards. So it's getting people to talk and ask for help, that's the main thing."

The family are now working with charities which support young people who are struggling with mental health issues.

"We want to tell Lewis' story, not for anybody to feel sorry for us, but to try and help people," he says.

Ian McCracken visited BBC Radio Ulster's studio to tell his son's story

Speaking about his late son has also helped the family to deal with their grief, and Mr McCracken says Lewis' teenage friends have been much better at consoling them than some of the adults in their lives.

"People don't know how to talk to you ... you see them crossing the road to try and avoid you because they don't want to talk about it," he says.

"I do understand, because I don't know if I'd know what to say to me."

However, he told the programme he wants to encourage people to show more support for families who have been bereaved through suicide, by going to speak to them about their loved one.

"We love talking about Lewis and if his story can help somebody else, we'll keep telling it."

If you're affected by the issues in this article, you can find support from BBC Action Line

Related topics

- Published15 April 2021

- Published18 January 2021

- Published19 October 2020