Irish language: Crossmaglen honours linguist John Hannon

- Published

'A contributor to Irish language, culture and tradition'

Without scholars such as John Hannon and his contemporaries, much of the Irish language, through song and written word, could have been consigned to history.

The Crossmaglen man was a collector, writing down the phrases, lyrics and prayers which had been passed down from generation to generation in south Armagh.

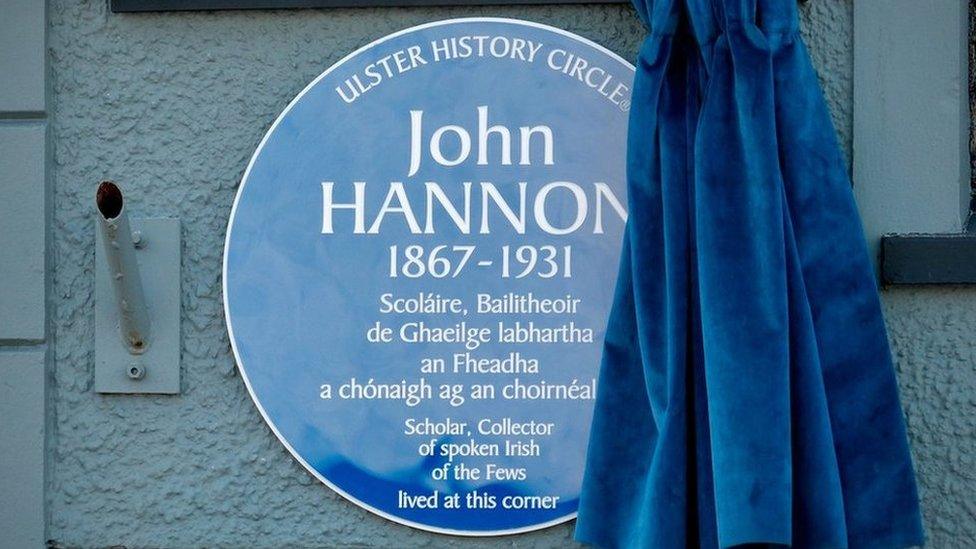

On Thursday, more than 90 years after his death, the linguist was honoured with a blue plaque by the Ulster History Circle.

Dr Gearóid Trimble, of Foras na Gaeilge, said Hannon was an important figure in "gathering and preserving what was left of that last generation of native Gaelic speakers" in the late 19th century.

His work took place in the context of younger generations learning English to seek opportunities for work or to emigrate.

"There was this huge stigma associated with the Irish language among those who were speaking and using it, but these local collectors, the likes of Hannon, being of the area, were able to break down the barriers," Dr Trimble told BBC News NI.

'Unique dialect of Oriel'

Born in County Leitrim in 1867, Hannon was the son of a Royal Irish Constabulary constable.

After John Sr took early retirement, the family moved to Crossmaglen, close to his mother's birthplace, and opened a shop in the centre of the village.

It was there that a young Hannon, who did not speak Irish, became fascinated by the language used by the family's customers and neighbours.

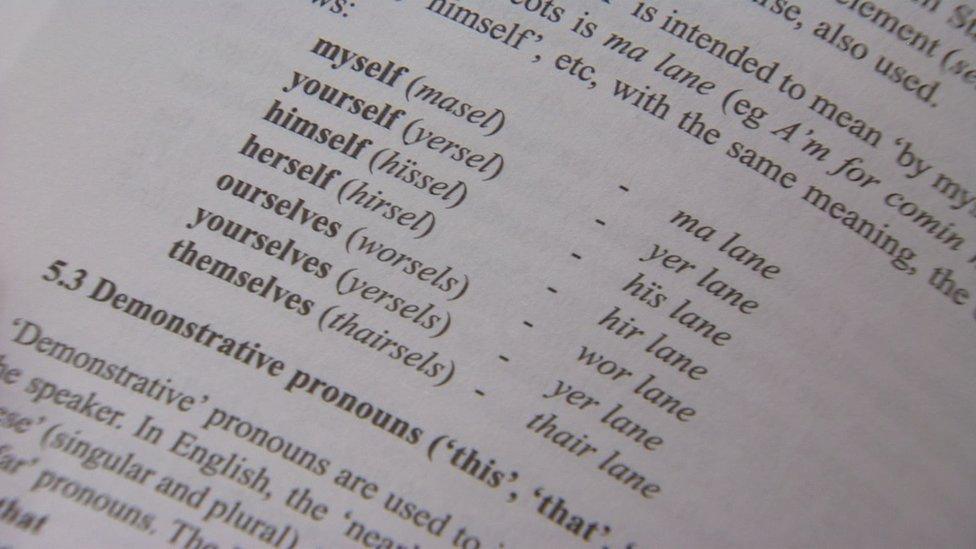

Adapting a key system for transcriptions, Hannon learned how to write down the words phonetically.

Dr Gearóid Trimble said Hannon amassed a valuable linguistic store of the Oriel dialect

Dr Trimble said his manuscripts would go on to include "over 130 songs that were commonly sung in the district during the 19th century".

Among these was 'Máire Chaoch' (Crooked-eye Mary), a satirical poem by Art McCooey, who was also honoured with a blue plaque in the area in 2014.

Drawing upon dozens of contacts, Hannon "managed to amass a huge valuable linguistic store of contents in the unique dialect of Oriel", Dr Trimble said.

The Oriel - or Oirialla - refers to a region along the modern Irish border including south Armagh.

"It wasn't connected to Donegal Irish, it wasn't connected to Connemara Irish, it was very much a form of dialect that managed to develop in its own right and it was cut off from other parts of Irish-speaking Ireland," Dr Trimble explained.

'The richest of poetry'

Hannon, who neither married nor had children, died aged 64 in 1931, after spending the last years of his life in a Newry workhouse.

Archbishop of Armagh Eamon Martin, the head of the Catholic Church in Ireland, said he "left behind him a very rich resource, a collection which will speak for generations to come".

Archbishop Eamon Martin said Hannon's legacy will inspire future generations

"The work that he did was perhaps forgotten, but I think that's a lovely lesson for everyone to realise that you can make a contribution which will be remembered a whole century after you've died and people will remember it and thank you for it," he told BBC News NI.

The singer Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin, who has written about the songs and traditions of the Oriel region, said the plaque was a long-deserved recognition.

"Other collectors and other linguists were using his material over the past 100 years for their own studies," she said.

Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin standing at the door of the shop owned by the Hannon family

"He did tremendous work. It's also very lonely work because you are witnessing the death of a great, great tradition and he was doing that alone knowing that, if he hadn't done that, then it would be lost.

"There were singers in this area who could recite a thousand lines of the richest of poetry," she continued.

"They may not have been schooled in the formal sense, but they had tremendous capacity for retaining oral memory."

Ms Ní Uallacháin said that during her research for songs to perform, she discovered in Hannon's work "so much memory that had been lost and could be returned to people in the community".

"It can't be measured, the value of that material for people and generations who are returning to the language and reclaiming their own traditions."

'Capsules of social history'

During the event on Thursday, the Oriel Traditional Orchestra, along with local singers, played some of the songs which Hannon transcribed, including Chuaigh an Mhaol, which has its origins in the village square where it was performed.

"This song was used to try and scare children to keep them in at night," said Dr Trimble, who is from Crossmaglen.

"The premise of the song was this bald, hornless cow would come chasing you. An awful lot of these songs are very unique to the area.

"They preserve place names, names of families, people, events - they are capsules of social history in their own right."

Local singers performed some of the songs Hannon transcribed

Eibhlín Mhic Aoidh, from the Ulster History Circle, who spoke at the unveiling, studied Irish at summer colleges in Donegal.

"Some of the songs I learned were actually songs that Hannon had collected and preserved," she recalled.

"Some of them are sung throughout Ireland.

"This event is folklore as a dynamic, living, breathing phenomenon. They are being sung by local people and by young people," she continued.

Chuaigh an Mhaol was performed in its traditional setting, the market square of Crossmaglen

"These are the songs John Hannon noted from old people at the end of the 19th century."

Ms Mhic Aoidh said the plaque was an example of the voluntary group trying to "shine a light on the contribution of local people to history".

'His work was invaluable'

Finance Minister Conor Murphy was also in attendance and described Hannon as a "very important figure, although not a very well known figure".

Growing up in south Armagh, he said he was aware of the area's "rich tradition of Gaelic poets, folklore and music", but had it not been for Hannon, much of it could have been "lost for all time".

"There are more prominent Gaelic scholars, and perhaps he wasn't as academic as the rest of them, but his work was invaluable," the Newry and Armagh assembly member said.

He said the "growing and vibrant" language community of today could trace its success back to the work of collectors such as Hannon.

The event came a day after legislation to provide for the "recognition and protection" of the Irish language took its first steps at Westminster.

The bill also provides for the development of the Ulster Scots and Ulster British tradition in Northern Ireland.

Related topics

- Published7 March 2022

- Published25 May 2022