Michael Watt: Trust failed to intervene on neurology misdiagnoses

- Published

5,448 patients were eligible for recall of which 4,179 people attended appointments.

The Belfast Health Trust failed to intervene quickly enough in the practice of a doctor which led to Northern Ireland's largest ever patient recall, an inquiry has found.

More than 5,000 former patients of neurologist Dr Michael Watt were invited to have their cases examined for possible misdiagnoses.

The inquiry found "numerous failures".

Health Minister Robin Swann said the report made very difficult reading.

Among the conditions being treated were stroke, Parkinson's disease and multiple sclerosis (MS).

The Independent Neurology Inquiry concluded that the combined effect of the failures ensured that patterns in the consultant's work were missed for a decade.

Key conclusions include:

The Belfast Trust should have intervened earlier, but failed to do so

Systems and processes in place to assure the public about patient safety prior to November 2016 failed

The effect of numerous failures ensured problems were missed for many years

Failures not confined to Belfast Trust - communications between different organisations and management levels were inadequate

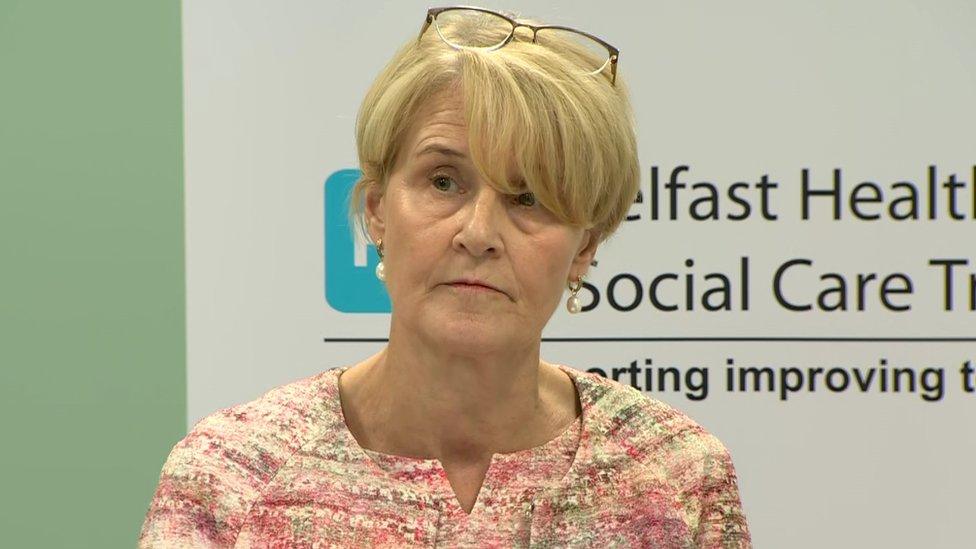

Dr Cathy Jack, Chief Executive of the Trust, apologised to Dr Watt's patients.

"The Belfast Trust let you down and many of you have suffered avoidable and unnecessary harm as a result," Dr Jack said.

Dr Cathy Jack apologised to Dr Watt's patients

"Whether that was through being given a diagnosis that was not correct, receiving incorrect treatment or medication, or having a procedure you did not need."

Patients who were affected by the inquiry results said they had been failed.

Health Minister Robin Swann apologised to those "who have been so badly let down".

"Today's report makes very difficult reading," he said.

Robin Swann has said he will be sharing the findings with his counterparts in Great Britain to ensure similar mistakes aren't made

While the reputation of the health service had been tarnished, Mr Swann said his priority was to ensure failures were not repeated.

Of the 5,448 people, including some children, who were recalled, 4,179 attended.

About one in five were told they had not been given an appropriate management plan for their condition, while a similar number had not been issued an appropriate prescription.

The inquiry, chaired by Brett Lockhart QC, has recommended that Northern Ireland's Department of Health should review its guidance in relation to complaints to ensure that patient safety is the overriding objective.

It also found a culture of medical professionals who were "apprehensive in raising a concern about the practice of a colleague".

Concern at lack of evidence

The inquiry was set up to examine the governance arrangements into how complaints were identified and handled.

Dr Watt's clinical practice has been investigated separately, by the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA) and in a final outcomes report which was published by the Department of Health this month.

Dr Michael Watt worked at the Royal Victoria Hospital as a neurologist

In 2021, he also voluntarily removed himself from the medical register ahead of a public Medical Practice Tribunal Hearing.

Dr Watt, who worked at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast, did not give evidence to the inquiry and a lawyer for the former consultant has referenced that he is experiencing ongoing mental health issues.

Mr Lockhart QC concluded it was a "source of significant and understandable public concern" that he did not appear before the panel.

This is an extremely critical report on the workings and governance of the Belfast Health Trust and the Department of Health.

The regulator, the General Medical Council, also comes in for some bashing.

In straight-talking language, the panel highlights numerous failings by management across a number of healthcare organisations.

While the intention of this inquiry was never to examine the clinical practice of Michael Watt, patients should get some comfort in the criticism of managers who have been named and a culture where it was easier to pass problems over.

Yet again, Northern Ireland is dealing with another public inquiry which highlights extreme failures in healthcare.

Again, patients are at the centre of a dysfunctional system which failed to put them first.

Mr Lockhart said the report was "fundamentally about the safety of patients".

He said the inquiry had sought to examine if patients were let down, if opportunities were missed to identify problems with Dr Watt's practice, and if earlier intervention would have made a difference.

In answer to all three questions, he said the panel answered "yes".

"The systems and processes in place failed" - inquiry chairman Brett Lockhart QC

Peter McNaney, Chairman of the Belfast Trust, apologised but said the trust had already taken steps to address some of the concerns outlined in the inquiry "including the introduction of clinical record review" and a system that gathers and holds all of the trust's information about its doctors.

Mr McNaney has said steps are being taken to address issues highlighted in the inquiry

"However, first and foremost, our thoughts today are very much with those patients who suffered avoidable and unnecessary harm whilst under the care of Dr Watt," Mr McNaney said.

The report, released on Tuesday, highlights concerns with management and found a culture of medical professionals "apprehensive in raising a concern about the practice of a colleague or querying discrepancies that arose".

"A pre-existing and deeply rooted medical culture which inhibits a flow of relevant information to the medical director's office was, in the view of the inquiry panel, a major factor in failing to identify potential problems with Dr Watt at an earlier stage."

Doctors raising concerns about other doctors may be "wary of committing themselves to a position", it continued.

"Consequently, matters which may urgently need investigation or a further review, are passed over."

In the case of Dr Watt, "there was sufficient information accessible prior to November 2016 to demonstrate a pattern of potential aberrant practice".

From as early as 2006, a "narrative" surrounding the consultant's work had developed, the inquiry found, with a "perception that Dr Watt's clinical ability was not in question".

Issues were defined as "administrative", while the former neurologist had a "history of either failure to comply with or unreasonable delay in providing or undertaking annual appraisals".

Dr Watt also had a private practice at the Ulster Independent Clinic, where there had also been "significant complaints" about his work.

The inquiry had defined terms of reference, but reflected that concerns raised about complaints and challenging the work of medical professionals will not be "unique to the Belfast Trust".

He added the "combined effect" of an "inadequate investigation" by the General Medical Council into a clinical complaint in 2012, the "failure to disclose significant complaints" to the Belfast Trust by the Ulster Independent Clinic, alongside failures of other health and social care trusts "compounded a pre-existing problem in the Belfast Trust".

'You cannot unknow'

The report, which is about 1,000 pages long, makes 76 recommendations; among them ensuring that healthcare providers apply the principle of "you cannot unknow what you know".

Such conversations about raising complaints cannot be regarded as "informal" or "off the record", Mr Lockhart explained.

The Department of Health should review its guidance in relation to complaints to ensure that patient safety is the overriding objective

Greater emphasis should be placed on learning, detecting misconduct or poor practice and improving services

The department should have in place an appraisals process which enables them to better assure patient safety

The statutory public inquiry was established in 2020 by Health Minister Robin Swann.

Professor Hugo Mascie-Taylor, who had previously been involved in the Mid-Staffordshire inquiry, was also a member of the panel.

Related topics

- Published21 June 2022

- Published20 April 2021

- Published19 December 2019

- Published26 July 2021