Galboly: The Glens of Antrim's hidden village

- Published

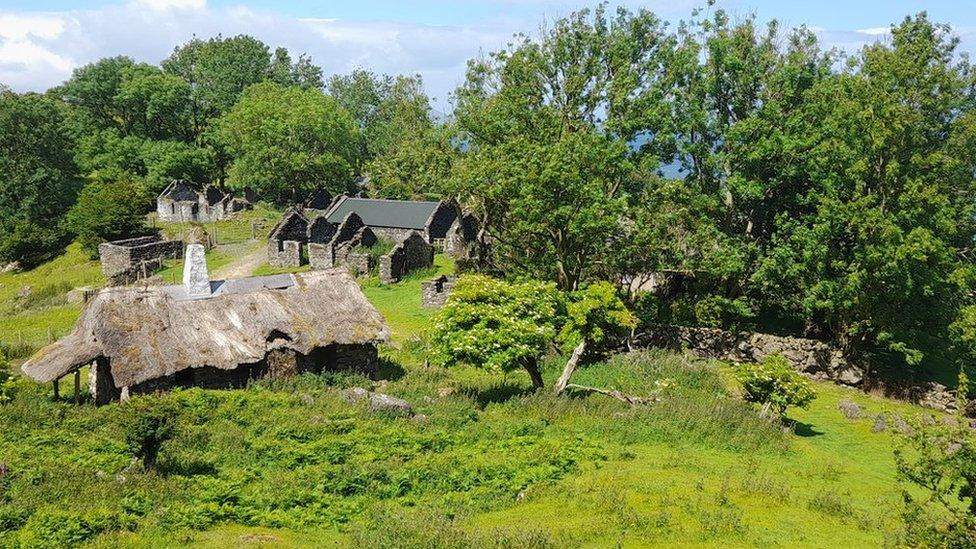

Upper Galboly was once home to about 60 people

Hidden away in the Glens of Antrim lie the ruins of a small village recently brought back to life for a blockbuster TV series.

Nestled in the hills along the east Antrim coast road is the Hidden Village of Galboly.

Once home to about 60 people, the final resident was a Cistercian monk living a life of solitude.

While it has recently come to public prominence after being used in Game of Thrones, its history opens a window into how people in small rural communities in Ireland lived off the land and worked together to survive.

However, before the establishment of the farming village - or clachan - that would become Upper Galboly, the area seems to have been home to robbers or outlaws who preyed on what would become the coast road, but at the time was more like a dirt track.

One story from the 1700s concerns a man named Jasper Ferry.

The village is nestled among hills in the Glens of Antrim

According to Donnell O'Loan, of the Glens of Antrim Historical Society, Mr Ferry returned from overseas to the port of Larne with a sum of money and jewels.

Apparently he was careless about discussing this fact and while travelling up the coast road he disappeared, presumed to have been robbed and murdered.

"In later years, probably around the 1950s, there was a limestone quarry [in the Galboly area] that was being used for I think refurbishing the coast road," Mr O'Loan said.

"The story is the bones or a skeleton of a person was found and the damage to his skull made it clear that it wasn't an accidental death.

"So the theory is that was possibly Jasper Ferry.

"It's just a story, but it's interesting that the name is still handed down and that would give some indication that there's some truth in it, it's not just a yarn."

The families raised livestock and grew whatever crops they could

The first official documentation of the farming village of Upper Galboly is from 1832, although as it already had 10 houses it is believed to have been established some time before that.

The village's beautiful location belies what must have been a tough life for its inhabitants - due to its position in the hills Galboly was said to enjoy three months of sunlight in the summer and very little for the rest of the year.

There was no water source, so the residents had to carry it from a well or spout about a kilometre away on the coast road.

The 60 or so inhabitants practised a form of co-operative agriculture known as rundale on the land they leased.

Pigs, cows, hens and sheep would be kept and different crops grown, including potatoes.

The village was recently used as a location for Game of Thrones

In the summer, boys from the village stayed with cattle brought up to the top of the hill - known as booleying - with stone huts having been found in the area.

On marshier ground, peat was dug and dried in the summer for use as fuel.

Fish and shellfish would also have been taken for food from the Irish Sea.

"There would be communal cooperation, so if a particular crop had to be brought in they'd all have helped to do that," Mr O'Loan said.

"The system of the clachan [village] and the system of the farming that was being carried on there really suited its surroundings very well.

"It was the best way to farm, it was the best way to live and exist in a little secluded valley like that with only a limited amount of land.

"That little valley with some decent fields in it where cattle could be grazed and some crops could be grown and then to make use of the mountain above for peat and for booleying - it was system that worked."

Cattle were taken to the top of the hill during summer

While it would be a life of hard work for many of the residents of Galboly - including the O'Boyles, Blacks, Murphys and Gibsons - Mr O'Loan said there would also have been a social aspect, helped by some of the family relationships between the households.

"People would have gone to each other's house, maybe different houses on different evenings and sat around the open fires with the red glow creating the atmosphere.

"Storytelling was very important - stories of ghosts, reminisces of past times, stories of the fairies, which were certainly very much believed in in the Glens of Antrrim in those days.

"As well as that there would have been music, there would always be somebody in the community who could play the fiddle particularly, so the jigs and the reels would have been played and that would have led to dancing.

The residents would often socialise together in one of the houses

"It is recorded that there was a shebeen [unofficial pub].

"Home-made alcohol would have been the most likely drink - a drop of the crathur - poiteen."

He added: "It was a very self-contained community where to a great extent they produced their own food and they made their own entertainment, they even made their own clothes."

While the population remained about 60 until the 1850s, by 1881 it was down to around 20, where it remained until the World War Two era when it dropped again.

"Emigration would have been a big reason," Mr O'Loan said.

"Like a lot of other people in the Glens of Antrim, people went to sea and became sailors.

"There wouldn't have been enough facilities and food and land to support a growing population."

He said when better houses were built in Carnlough, Glenariff and the surrounding areas where there were more facilities, people moved.

The Galboly residents would have supplemented their diets with fish and shellfish

"Sometimes the girls would move way when they got married to somebody from the surrounding areas," Mr O'Loan said.

"If men were sitting up in Galboly, they weren't mixing or meeting other girls or women so you got to the situation that living in the place were elderly unmarried men."

When the last of the descendants of the original inhabitants had gone, the village had one final solitary resident.

Brother Veder O'Kane was a Cistercian monk who lived in the village for decades before he passed away in 2013.

"He preferred to live the isolated life of the hermit, he liked the solitary life basically," Mr O'Loan said.

"He was living his own life, he was there for quite a number of years.

"We all knew he was there and he came from Galboly round to Mass in Glenariff.

"You could imagine when he was up there he was by himself to a great extent, because before the days of Game of Thrones very few people went up there to visit."

More people now visit Galboly after its exposure on Game of Thrones

Game of Thrones temporarily transformed Galboly into Runestone in the Vale of Arryn for series five and six of the HBO series.

That has seen an uptick in interest and visitors to the site, though it should be remembered the land is owned by local farmers.

You can't help wondering what Veder O'Kane or some of the families who toiled and socialised together in the tiny village would have made of it all.