NI courts backlog 'may not be cleared until 2028', says minister

- Published

Naomi Long says dealing with the courts backlog was taking too long

The courts backlog caused by Covid-19 may not be cleared until 2028 without extra resources, the justice minister has said.

Naomi Long said the "serious issue" of dealing with the problem was moving slower than it needs to.

This is because no power-sharing executive has been formed despite an election two months ago.

The DUP will not enter an executive until its concerns about the Northern Ireland Protocol are dealt with.

Mrs Long and other ministers remain in office in a caretaker capacity.

Claire Rafferty, a survivor of sexual abuse, said there was an urgent need for the system to be quicker because "the longer it takes, the longer the hell continues".

Ms Rafferty, from County Down, was abused as a child by her cousin, David Andrews, who was seven years older than her.

She reported the crimes to the police in 2018.

Earlier this year, Andrews, 43, from Dundonald, pleaded guilty to several charges including attempted rape and indecent assault.

Two counts of rape were left on the books.

Andrews was given a three-year suspended prison sentence for the crimes, which he committed between 1990 and 1995.

"I have lived through hell for years"

Ms Rafferty, who has waived her legal right to anonymity, said: "Something needs to change to allow survivors to get through the process a lot more smoothly.

"I have battled with depression and anxiety for a long time, and my anxiety has been through the roof.

"It's not fair that a victim goes through so much as they have, and then there's another battle to have a case heard in a reasonable amount of time."

Several reviews in the last two decades have identified slow processing times as being a particular challenge for the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland.

In 2018, a report by the Audit Office found court cases in Northern Ireland typically took twice as long as in England and Wales.

More on this story on the 5 Minutes On podcast: Pursuing justice: 'The longer it takes, the longer that hell continues'

Figures show the situation was improving until the beginning of the pandemic.

Direct comparisons with other parts of the UK are difficult.

Scotland has a very distinct legal system, and the way in which statistics are recorded are different from England and Wales.

Figures relating to crown court cases - the most serious criminal offences - suggest Northern Ireland still lags behind.

An Audit Office report has found court cases in Northern Ireland typically take twice as long as in England and Wales

There are two routes for cases to reach the crown court.

Suspects are either charged directly by the police, or they are "summonsed" to be formally charged in court, after prosecution lawyers have analysed a file which police have compiled.

In Northern Ireland, case completion times are measured from the point at which a crime is reported to police, or detected by police, until the end of court hearings.

The BBC has obtained statistics under the Freedom of Information Act relating to case completion times during the last quarter of 2021.

These show that the median time for cases where defendants were summonsed was 977 days.

The median figure for cases where defendants where defendants were charged by police was 523 days.

In England and Wales, completion times are measured from the point at which a crime is committed - not reported or detected.

Figures from the Ministry of Justice in London show that in the last quarter of 2021, the median completion time for all crown court cases was 412 days.

The cases which take the longest are those involving sexual offences.

'Four years on standby'

In Northern Ireland, the median completion time is 712 days - just short of two years.

"I had so many blips along the way where I felt I was the one having to push things forward, asking for updates," Ms Rafferty said.

"At one point it was decided more time needed to be allocated for the trial, that it would need two or three weeks instead of one.

"So it was delayed until October last year, then until February this year.

"I appreciate Covid has mixed things up for everybody. But I've had four years where I've been on standby - just waiting and not quite knowing what the next step is."

Mrs Long said additional money to help public services recover from the pandemic had recently enabled the court system to operate at 110% capacity, which has been reducing the backlog.

But she warned: "That money has now stopped. Unless we get extra investment - instead of seeing the backlog ended by early 2024, we could be looking at 2028 before we're in that position."

She told BBC News that legislation passed earlier this year would ease the "committal" process by which cases are moved through the courts.

But no more legislation can be passed unless the devolved assembly is restored.

The DUP is blocking the restoration of the NI Executive over the Northern Ireland Protocol

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is currently blocking the Assembly from meeting, and vetoing the formation of a governing coalition.

The DUP has said the Brexit trade border with the rest of the UK, known as the Northern Ireland Protocol, has removed the basis for power-sharing on which devolution is founded.

Mrs Long - who is leader of the cross-community Alliance Party - said she could not fully reform the criminal justice system without being able to pass legislation.

"We would like to increase the number of what are known as non-court disposals - less serious cases that in terms of volume take up a lot of court time, but could be dealt with in other ways," she explained.

"We would need new legislation to do that."

Ms Rafferty spoke about a number of other issues which she felt made her experience of the justice system more difficult than it needed to be.

'Daunting'

She said when she first went to a police station to report what had happened to her, "having to stand in a public place and say I was sexually abused as a child was really daunting".

"When they let me in, the next person I saw was another man, and because I was abused by a male, it unsettled me."

She said unexpected developments in the case also caused her unease.

"I had done a pre-trial visit to Belfast Crown Court, where there was a different entrance for me so I didn't run the risk of walking into my abuser.

"But about a week before a hearing was due, I was told the court was being moved from Belfast to Newry, somewhere I'm not familiar with."

She also would like the law to be changed so defendants who plead guilty at a late stage are not given credit towards a more lenient sentence, and so that people can have have information about whether a sex offender lives near them.

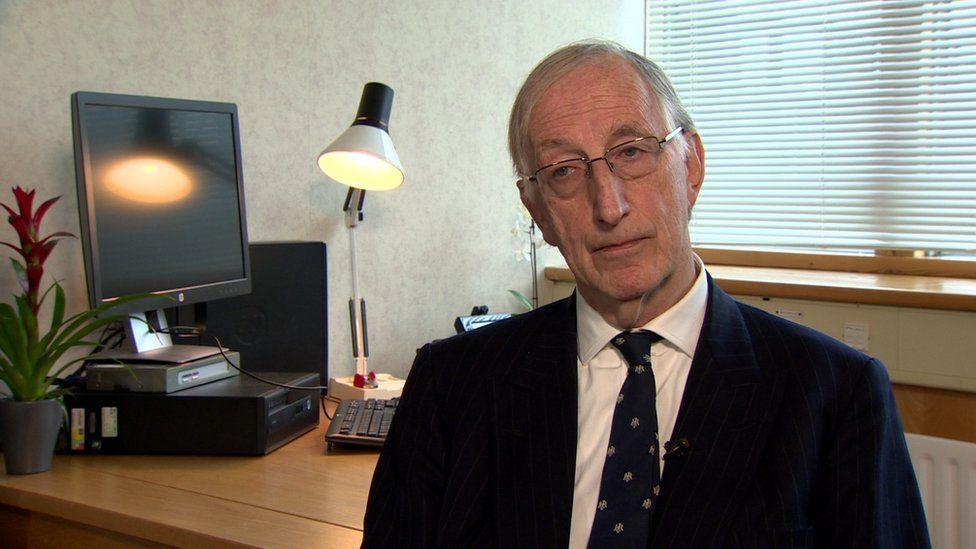

In May 2019, the retired judge Sir John Gillen published a review commissioned by the devolved government on how the justice system deals with sex crimes.

Sir John Gillen's review touched on societal issues such as relationships education, and culture in organisations

Mrs Long said more than half of the 253 recommendations had been fully or partially implemented.

But she said progress was being stalled by the political stalemate.

"Many of the societal changes which Sir John recommended can't be driven by my department alone, such as issues around relationships education, and culture in organisations.

"I'm determined to do all I can, but it is challenging when you don't have a functioning Executive in place to bring it all together."

Ms Rafferty said she hoped that by speaking out she could encourage change in the system.

'I've fought for me'

She said she wanted to encourage other abuse survivors to come forward to the police - and that in spite of the problems she experienced, she was still glad she pursued justice.

"I've fought for me, and fought for that little girl who was too scared to speak up.

"I've done right by that little girl, and I'm doing right by anybody else who was abused. I want to give them hope that you don't have to be stuck in that circle.

"If I can make the tiniest bit of difference to one person - and let them know they're not alone - it would mean the world to me."

Related topics

- Published3 August 2022

- Published15 July 2020