Harps Alive festival celebrates revival of ancient tradition

- Published

The Harps Alive festival opens with a concert at the Mussenden Temple on Saturday

Harp players are gathering in Northern Ireland for a unique cross-border, cross-community festival celebrating the instrument and its rich history.

It begins on the north coast on Saturday and continues with events in Belfast and Dublin later this month.

It marks the 230th anniversary of an event in Belfast when harpers were brought together in a Protestant-led bid to protect what was then feared to be a dying tradition.

For centuries, the harp has been one of the most recognisable symbols in Irish society.

It remains so today as the official emblem of the Irish government. Harps are also stamped on the back of Irish euro coins as a national motif.

However, harpers' fortunes declined over the turbulent course of Anglo-Irish history, and in 1792, a Belfast-based movement was motivated to safeguard the tradition.

Historically, harpers enjoyed a significant role in old Gaelic clan society.

They were considered important members of Irish chieftains' entourage in a culture dominated by oral traditions.

"They had a knowledge of the stories and the poems of the clan and they were prestigious within the clan," says John Gray, one of the festival organisers.

John Gray (centre) with some of the performers at Belfast's Clifton House

But he explains that after the defeat and break up of the Gaelic clans, talented harpers had to look elsewhere to earn their keep because the number of wealthy homes where they could be assured of a good welcome and a good income from music declined significantly.

The people who led attempts to protect harping tradition in the 18th Century were "almost universally from the Presbyterian merchant class", according to Mr Gray.

"The old life of the itinerant harper, moving from gentleman's house to gentleman's house, was dying out and they were anxious to provide a platform for the music but, above all, to record it and to ensure that the tradition didn't just die a death."

Blind children recruited

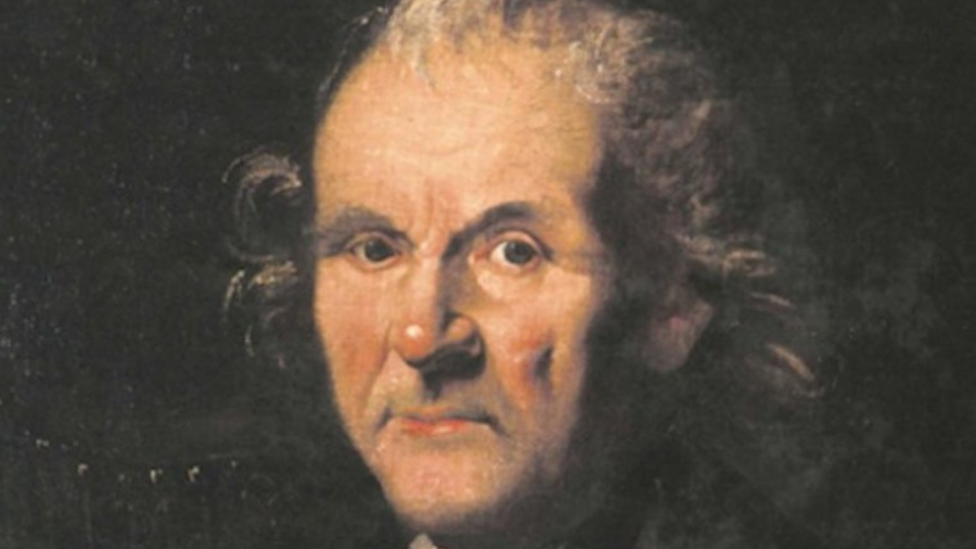

Protestant merchants organised the Belfast Harpers' Assembly in 1792, bringing together 11 harpers, including renowned musician Denis Hempson, who was then 97 years old.

Denis Hempson was considered to be among Ireland's greatest harpers

Seven of the 11 performers were blind, but Mr Gray explains this was not unusual at the time because blindness was more common and harp societies specifically recruited such youngsters.

"The question was, if you had a child who was blind, what occupation could a blind child pursue? And one of the avenues was music," he said.

The 1792 event not only showcased the talents of the finest harpers in Ireland, it was also an attempt to record their music as a legacy for future generations.

That task fell to a teenager - the 19-year-old Edward Bunting who was a talented organist at a Presbyterian church in Belfast.

"Edward Bunting actually transcribed the music that was played, and in terms of legacy and the possibilities of reviving the harping tradition, Buntings' work was absolutely crucial," says Mr Gray.

Bunting's transcriptions of the 1792 assembly were subsequently published in three volumes called The Ancient Music of Ireland.

From his teenage years onwards, Edward Bunting worked to preserve Irish musical legacy

Some of Bunting's musical manuscripts are currently stored at Queen's University Belfast, and this week they are being dusted off for a new generation who will play the tunes on Saturday evening.

Northern Ireland harp teacher Katy Bustard has been delving through Buntings' archives and she has taught some of that ancient music to her teenage pupils especially for the festival.

'Original Danny Boy'

Among performers showcasing Buntings' tunes will be 14-year-old Coleraine schoolgirl, Phoebe Kelly.

"They were quite difficult to learn, but I enjoyed learning them because I like the history behind them and I find it very interesting," she says.

"One of them is the original tune of Danny Boy called The Young Man's Dream."

Danny Boy's origins are an ongoing source of debate, but Bunting's work is believed to have influenced the tune of what became one of Ireland's best-known songs.

"You can hear bits of it in it but not too much," says Phoebe.

Phoebe Kelly, 14, is one of the younger performers at the festival

Phoebe began learning to play the instrument when she was nine, and was the second person in her house to take up the harp, following her older sister.

"Because it's an expensive instrument, my mum thought it would be a good idea if I started as well," she says, agreeing her parents wanted to get their money's worth out of the investment.

Phoebe also plays piano and violin but prefers the harp above all, practising for up to an hour most days.

As well as connecting her with the past, Phoebe also hopes the harp will provide a bright future.

"I would love to be a harp teacher some day and I love going to these events and performing," she says.

She is particularly looking forward to Saturday's concert at the Mussenden Temple on the north coast.

The location was chosen as it is close to where 1792 performer Denis Hempson lived, whom Phoebe describes as an "amazing" harper.

"It is important to keep the tradition going and I guess the Mussenden event will be good for that. It keeps the legacy of Denis Hempson going as well, so it's very important."

The festival is jointly led by the Reclaim the Enlightenment group in Northern Ireland and the all-island organisation, Harps Ireland.

It will bring more than 50 harpers to Belfast and features concerts, workshops, historical talks and an exhibition.

Continuing its cross-community theme, venues hosting events include the Cultúrlann Irish arts centre in west Belfast and the nearby Shankill Road library.

Related topics

- Published31 March 2021

- Published24 February 2020