Boris Johnson, Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol

- Published

Boris Johnson rose to the highest ranks of UK politics on the back of Brexit.

He was the face of the campaign group Vote Leave and in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum the new prime minister Theresa May made him foreign secretary.

Within three years, he had deposed her for taking an insufficiently hard line on Brexit.

He then fought and won an election on the promise that he would "get Brexit done".

He did deliver a Brexit deal with the EU but the treatment of Northern Ireland remains unfinished business, which has poisoned several sets of political relationships.

How did Mr Johnson's position on Northern Ireland and Brexit evolve?

November 2018: The DUP conference

Boris Johnson was the star attraction at the DUP party conference in Belfast with his speech cheered to the rafters.

At this time the Conservative government required DUP support to wield power, although that relationship was increasingly tense.

Boris Johnson and then DUP leader Arlene Foster and MP Nigel Dodds at the party's 2018 conference

Two weeks before the DUP conference, then-prime minister Theresa May had agreed a draft withdrawal agreement with the EU.

It included an arrangement for Northern Ireland known as "the backstop" - it would mean that in the absence of some other solution to maintain an open Irish border, Northern Ireland would continue to follow EU rules on goods and customs.

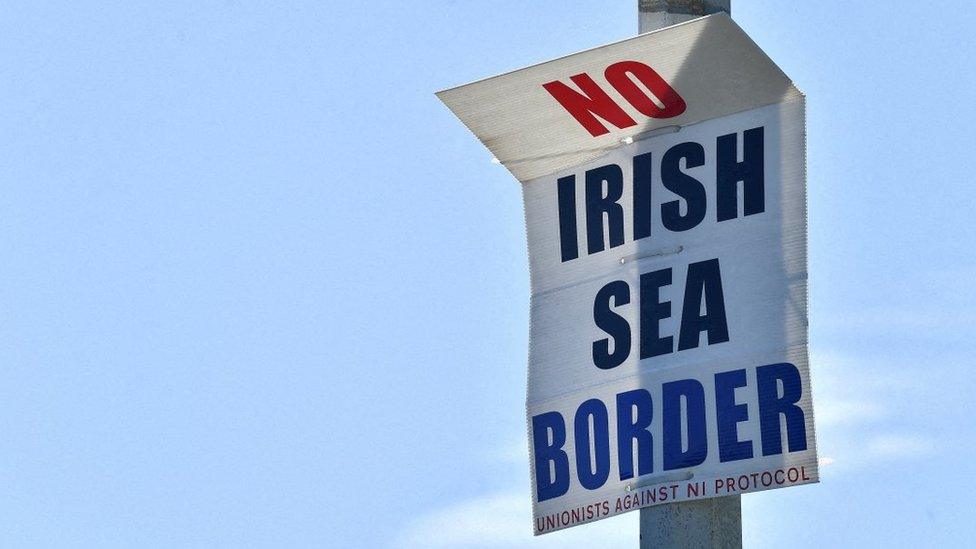

The DUP was strongly opposed to this, seeing that it would mean a trade border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

From the DUP's perspective, Mr Johnson arrived with clean hands: he had resigned from the government in July saying that Mrs May's moves towards a softer Brexit would mean the UK heading "for the status of a colony".

That language was repeated to the DUP faithful.

Mr Johnson told them the backstop would leave Northern Ireland as "an economic semi-colony of the EU".

He added that new regulatory checks and customs controls would be damaging to "the fabric of the union".

He promised that no British Conservative government "could or should sign up to any such arrangement".

However that promise would not last a year.

October 2019: Boris meets Leo

Mr Johnson became Conservative leader and prime minister in July 2019 and by August he took his opening shot at the EU.

In a terse letter to European Council President Donald Tusk, the prime minister said the backstop risked undermining the Northern Ireland peace process, was unviable and anti-democratic.

Boris Johnson wrote to Donald Tusk (right) in 2019 to set out his demands for a Brexit deal

He called for "flexible and creative solutions" and "alternative arrangements" - based on technology - to avoid a hard border.

But, by the end of September, the prime minister's position was shifting as the clock ticked towards an end of year deadline.

His government floated the idea that Northern Ireland could continue to follow EU rules on food and agriculture as part of a package of measures to keep a soft Irish border.

The DUP was initially on board with that idea as it would need consent from the Northern Ireland Assembly, which would likely have given the party a veto.

However, the Irish government and the EU were not convinced as the plan would have potentially meant a new customs border in Ireland.

They were also concerned an up-front veto for the DUP could prevent the "all-island regulatory zone" from ever materialising.

But then came a meeting with the then-Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Leo Varadkar at Thornton Manor on Merseyside.

After their meeting, Boris Johnson and Leo Varadkar said they could "see a pathway to a possible deal"

At that meeting, Mr Johnson seemed to have been convinced that a broader alignment between the EU and Northern Ireland was possible - just a week later he signed up to the Northern Ireland Protocol.

It unambiguously created an Irish Sea border - breaking Mr Johnson's promise to unionists.

It did include a role for the Northern Ireland Assembly, which could overturn the arrangement four years after its implementation.

But that would be by simple majority, meaning unionists would not have a veto.

The DUP, which at that stage was still propping up the Conservative government, was aghast.

December 2019: General election

With the DUP offside, Mr Johnson would need an election to shift the parliamentary numbers in his favour.

The election campaign would mark the beginning of a long period in which Mr Johnson would either misrepresent or misunderstand his own deal.

Within four days of the deal being signed, civil servants had produced an analysis which clearly explained that the protocol would mean checks and controls on goods going from Great Britain to Northern Ireland - an Irish Sea border.

But during the election campaign Mr Johnson repeatedly said there would not be checks.

A leaked Treasury analysis contradicted Mr Johnson stating that: "The Withdrawal Agreement has the potential to separate Northern Ireland in practice from whole swathes of the UK's internal market."

It also correctly anticipated the way in which the protocol would be perceived by many unionists: "Northern Ireland symbolically separated from the union/economic union undermined."

The Conservatives won a landslide majority in the December 2019 general election

But this issue gained almost no traction in the election campaign and Mr Johnson romped to victory.

In the EU, exasperation was growing about Mr Johnson's characterisation of the deal.

In January 2020, the EU's chief negotiator Michel Barnier came to Belfast to spell it out in a speech: the deal meant that checks on goods entering NI from GB were "indispensable".

But as late as August 2020, Mr Johnson was still saying there would be an Irish Sea border "over my dead body", despite the fact the government had already submitted applications to the EU to create border control posts at Northern Ireland's ports.

September 2020: Walking it back - part one

For much of 2020, there was little progress in explaining how the protocol would be implemented.

Then in September there was a dramatic intervention from Brandon Lewis, the Northern Ireland Secretary and Boris Johnson loyalist.

The protocol keeps Northern Ireland aligned to EU product standards

He told the House of Commons that the government was bringing forward a piece of legislation, the Internal Market Bill.

That bill, he said, would break international law in a "very specific and limited way" by overriding some parts of the Northern Ireland deal.

That was aimed at two parts of the deal where the UK believed the EU had over-reached.

In the end, the law breaking didn't happen as the EU and UK patched up a mini-deal but it demonstrated Mr Johnson's growing regret at what he had agreed to.

July 2021: Walking it back - part two

UK-EU relationships deteriorated and, by July, Mr Johnson was describing the protocol as having profound economic, political, social and commercial impacts.

A major EU blunder in January set the tone for the year.

The European Commission was under huge pressure in a dispute with AstraZeneca over the provision of Covid vaccines.

As part of a package of measures announced, the commission said it would use Article 16 to impose export controls on vaccines going to Northern Ireland to prevent this route acting as a backdoor into the rest of the UK.

The Irish government, which had not been consulted, was aghast, knowing that the move would infuriate unionism.

The UK's approach to the protocol then sharpened as Mr Johnson handed the brief to Lord Frost.

This command paper has effectively remained Mr Johnson's Northern Ireland Brexit policy ever since and forms the basis of the new Protocol Bill, which if passed will give UK ministers sweeping powers to unilaterally change the protocol.

The EU believes the bill breaks international law, the Irish government has described it as a new low and the DUP say they will not return to government until the protocol is dealt with.

It now falls to a new leader to fix these relationships.

- Published2 February 2024

- Published7 July 2022

- Published5 July 2022