Northern Ireland Troubles: How punk music created its own riot

- Published

Fearghus Roulston decided to take a deeper look into the punk scene in Northern Ireland after reading about the English punk movement

When the Troubles was at its peak in Northern Ireland, punk music was creating its own riot.

But Protestant and Catholic punks were fighting for the same team - most of the time.

Anecdotes from the punk music scene show how subculture and conflict co-existed.

The conflict, known as the Troubles, began in 1969 and led to more than 3,500 people losing their lives over a period of almost 30 years.

"I learned that young Catholics and Protestants both took part in the punk scene, which was fairly unusual for the time," said Fearghus Roulston, who has written his PhD thesis on the topic.

But the University of Brighton researcher added that "this didn't mean they existed outside of sectarianism or of violence, which still affected their lives in lots of ways".

Whilst living in Manchester, Mr Roulston read a book about the English punk movement and decided to take a deeper look into the scene in Northern Ireland.

His findings are due to be published in a book next month.

'Never met a real one'

"You're obviously never just a punk - you're also a student, a worker, someone who lives in whatever neighbourhood of Belfast or whatever town outside of Belfast," he told BBC News NI.

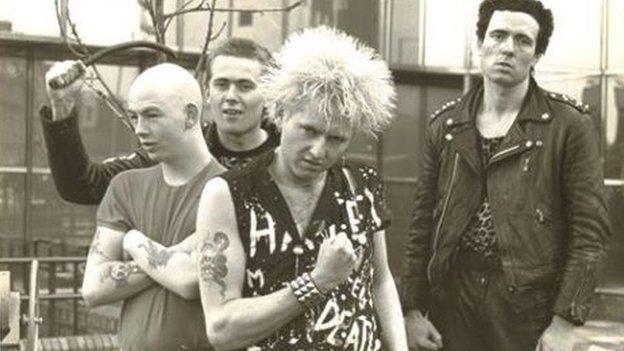

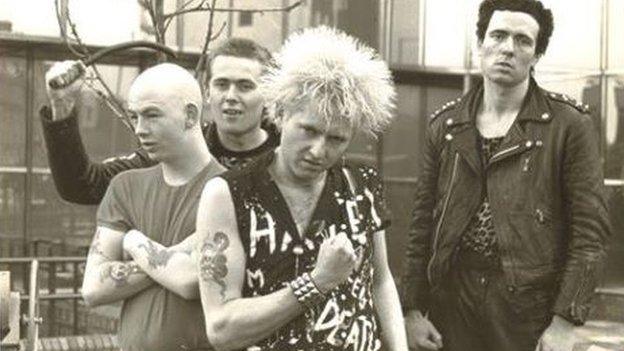

Petesey Burns, from punk band The Outcasts, added to the research, explaining that before joining the punk scene, he would have never met Protestants.

The Outcasts, were one of the pioneers of the Belfast punk scene, releasing singles such as Frustration and Self Conscious Over You

"Didn't happen, there were none near me, didn't go to my school - we were in our ghetto," he said.

"And you knew what they were, and they were supposed to be the enemy and that, but you know, whatever, you never met a real one.

"Until I started playing in the bands, and you came into the centre of Belfast, and I was meeting guys from the Newtownards Road, meeting guys from other parts of Belfast.

"And how could we support things like Rock Against Racism if you're having sectarian thoughts? You can't say, 'well racism is wrong but sectarianism is OK', you can't do that. So it was really refreshing."

On 20 October 1977, a riot nearly broke out on the streets of Belfast.

This time, it was because punk had arrived.

Terri Hooley, founder of famed Northern Ireland record label Good Vibrations

During "the Battle of Bedford Street", hundreds of teenagers from across Northern Ireland were left disappointed when The Clash had to cancel their Ulster Hall concert after the insurance company withdrew their cover.

The founder of Good Vibrations record label, Terri Hooley, described it as "the only riot of the Troubles where Catholics and Protestants were fighting on the same side".

The protest was documented in the song Cops, performed by punk band Rudi and penned by Brian Young.

"It wasn't a proper Belfast riot, it was like kids in funny clothes, you know what I mean, a few windows were broken and people sat in the road," Mr Young told the researcher.

"But the police just went in as if it was. It was just stupid."

Mr Roulston's research is largely composed of people's lived experiences.

'There's an alternative'

While some of them are sad, he said, "there is lots of humour in how people talk about the past as well".

"What immediately springs to mind are people talking about making their own clothes, trying to spike up their hair with Brylcreem, cutting up pyjamas, wearing tie-dyed doctors coats," he said.

"One guy who used a bathplug and his mum's 18-carat gold necklace as chains; a famous story about a woman who used a kettle as a handbag - funny but also quite touching to me in terms of people trying to have fun and improvise in difficult circumstances."

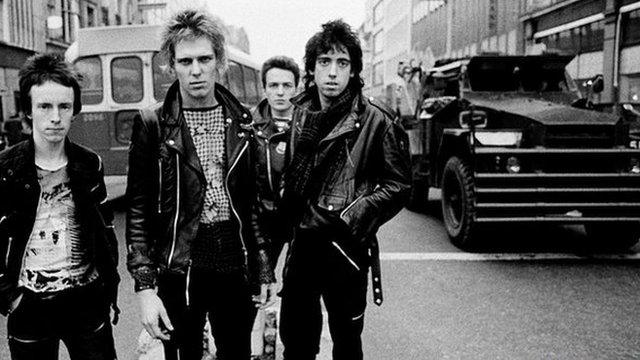

Researcher Fearghus Roulston, left, found that the punk scene brought young Catholics and Protestants together

Mr Roulston's work is peppered with tales from bars and clubs.

Some punks spent a lot of time in the company of members of the LGBT community, which some venues embraced.

Alison Farrell, from Dungannon in County Tyrone, said one Belfast bar "was sort of, again, just crossing all boundaries", describing the smell of drugs as patrons walked in as such it "would have absolutely blown your head off".

For many, being a punk offered something different to the status quo.

"The big thing that was happening around you is that there were shootings, you know, Dungannon was fairly badly hit - I mean all towns were," said Ms Farrell.

"You're trying to get your head around what side is right and what side is wrong, and for somebody like Stiff Little Fingers to come on and sing Barbed Wire Love made you stop and think, 'there's an alternative'," she said.

Related topics

- Published29 April 2015

- Published18 June 2014