Ash dieback disease ravages Northern Ireland's native trees

- Published

The disease causes trees to die at the top of the leaf canopy

"I'm about to spoil every country walk you'll have from now on," Mark Feather told me, as we strolled up the path through Carnmoney Hill Wood.

The Woodland Trust tree safety adviser wasn't wrong: Since he pointed out the clear signs of ash dieback on so many of the trees around us, it has become just about all I can see everywhere I go.

And I am not alone. Many readers have contacted BBC News NI to express concern about trees from south Armagh to north Antrim and County Down to County Fermanagh.

It is 10 years since the tree disease was detected in Northern Ireland and it has been quietly ravaging our native ash trees ever since.

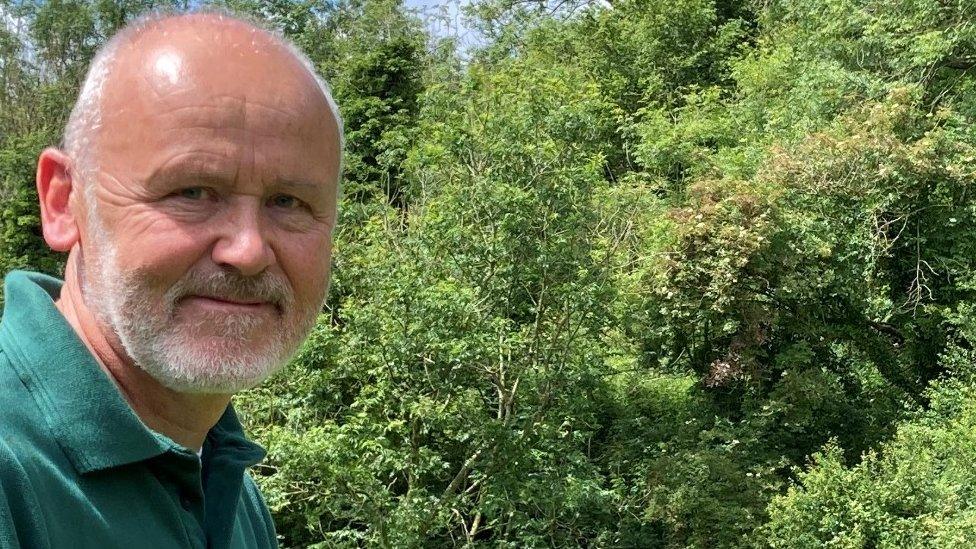

Mark Feather says more mature trees can withstand the effects of ash dieback better than saplings

Years of slow progress mean its effects are now becoming obvious.

"It's the tops of the trees or the crowns of the trees that are dying back and you can see the dead wood forming, but it's quite a mixed picture," said Mr Feather.

"Generally, it's the younger trees that show more advanced signs.

Ash dieback spreads through spores from infected trees landing on leaves and travelling into the trunk

"But as we can see, we've got some of the more mature ones that are also suffering. So it sadly is mixed. "

Ash dieback is believed to have arrived on imported saplings and was first detected in November 2012.

More than 90% of ash trees in Northern Ireland are now thought to have the disease, which spreads through spores from infected trees landing on leaves and travelling into the trunk.

How does ash dieback develop?

More mature trees can withstand its effects for longer, said Mr Feather.

"Whilst they might be infected, they'll actually still hang around so they're a bit stronger than the younger ones - they die off quicker," he said.

Hurling and health at risk

Native ash trees are culturally significant: They were named in ancient Brehon law on the island of Ireland as one of the "Airig Fedo" - nobles of the wood - because of their economic importance.

There will be no native ash available to make furniture - or hurls - within a decade, predicts John Hetherington

They are well-suited to the climate, fast-growing, and provide flexible wood that has a range of uses.

Those in the forestry sector are worried.

"Within the next five to 10 years there will be no native ash available for the furniture industry, for hurley stick manufacturers, for oars for boats and other specialist uses that ash timber is very well suited for," said John Hetherington.

Mr Hetherington, who runs a forestry company in County Tyrone, has safety concerns too.

Large dead branches can be a safety hazard during storms

"There's lots of ash trees on roadsides," he said.

"The sad reality is that each storm from now on for the next five to 10 years, we will have larger and larger limbs of ash trees splitting off from the main tree and unfortunately there's a health hazard there.

"And it would be helpful if Forest Service would assist with grant aid to remove especially the dangerous trees."

The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Daera) said it provided advice to landowners on managing affected trees, something a spokesperson said was "particularly important where affected ash trees are in proximity to areas used by the public".

A forest protection scheme has been introduced, added the spokesperson, through which woodland owners are encouraged to create more resilience to disease through species choice and diversity in their woodlands.

More details about the scheme, which is currently live, can be accessed through Daera's Grants and Funding Hub, external.

Beetles and flies

But dieback is not the only disease keeping insect expert Florentine Spaans busy.

Florentine Spaans is concerned Ash Dieback may make trees more susceptible to parasites like the sawfly, which strips leaves off twigs

"Also on the horizon is the emerald ash borer, which is an extremely serious pest," she said.

"It's a blue crested beetle native to eastern Asia, which has jumped to the United States where it's caused the death of tens of millions of ash trees.

"Since then, it's actually jumped over to Russia and has moved into Eastern Europe.

"So really, it's only a matter of time before it naturally spreads across the rest of Europe and will very likely reach here as well."

The Agri-Food & Bio-Sciences Institute, where Flor is a researcher, is running a Daera-funded project to study whether ash dieback pre-disposes the tree to other parasites like the sawfly, which was first detected in 2016.

"It has not spread beyond Belfast," she said. "On its own, it's of little concern."

"It does defoliate trees every year, forcing them to flush and that takes an energy toll.

"But on its own, we wouldn't be so worried."

Genetic resilience hopes

Northern Ireland is one of the least forested parts of Europe, with just 8.7% woodland coverage.

Only a tiny 0.04% of that is ancient woodland, areas that have been continuously forested for four centuries or more.

As far as ash dieback is concerned, there is a glimmer of hope on the horizon.

"If there's lots of affected trees around and there's one that's looking really healthy, those are the ones worth keeping an eye on because they might be the future trees," said Mark Feather.

"Each ash tree generates thousands of seeds, and the hope is that some of those have got a genetic resilience.

"So the more ash around, the more seedlings we get and potentially those will be the ones that come up and regenerate the ash population."

Related topics

- Published8 March 2019

- Published20 July 2022

- Published8 May 2020