1922: The lasting legacy of Irish Civil War executions

- Published

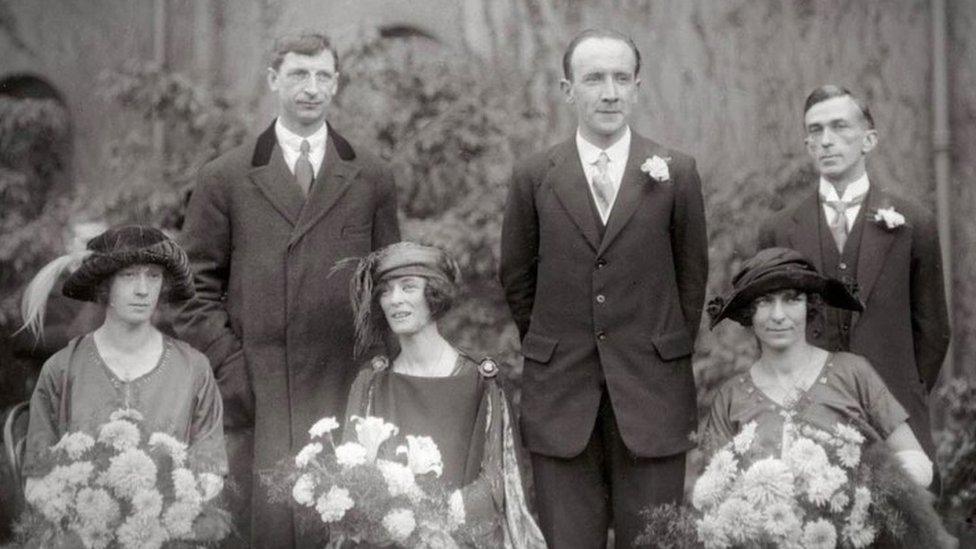

Kevin O'Higgins (centre), signed the execution order for his best man Rory O'Connor (right); Éamon De Valera (left) was also at O'Higgins' wedding

In October 1921 a young Irish independence leader posed for photos on his wedding day with his bride and his best man.

Just over a year later, in December 1922, Kevin O'Higgins signed the execution order that condemned his best man to death.

Rory O'Connor was executed by firing squad.

The execution of anti-Treaty IRA fighters by the new Irish Free State during the Irish Civil War remains one of the most infamous aspects of the 11-month conflict.

The executions began a century ago this month and continued until 30 May 1923, by which stage 81 people had been executed.

The execution of O'Connor remains symbolic of a conflict which pitted former comrades in the fight for Irish independence from Britain against each other.

In the summer of 1922 the military forces of the new government in Dublin had made big gains against the IRA fighters who were opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty which had brought an end to the conflict with Britain.

But in the autumn the war was dragging on, anti-Treaty fighters were using guerrilla tactics and there was no immediate end in sight.

In September the new government had passed legislation commonly known as the Public Safety Act, which imposed martial law and gave military tribunals the ability to impose punishments - including the death penalty - for a range of offences including possessing arms, ammunition or explosives.

Cycle of violence

Eunan O'Halpin, a retired professor of contemporary Irish history at Trinity College Dublin, says there was a feeling of "exasperation" in the new government that the anti-Treaty forces would not surrender.

"By late August they don't have a single village and there's a kind of exasperation there on the Free State side because the republicans militarily won't give up and they politically have no leadership with whom effective negotiations can take place," he says.

"And so you get the emergence of a pattern of small-scale War of Independence-style engagements, which are much harder for the National Army.

"The rebels are no longer taking territory and taking buildings, they're now doing it on a kind of hit-and-run basis and that builds irritation within the cabinet about these kind of killings."

Prof O'Halpin also points out that since early 1922 civilians were being executed - mainly by anti-Treaty fighters - after being accused of spying, while there were also killings of Protestants, such as in Bandon Valley, which he describes as "plainly sectarian in impact".

The uncle of the new leader of the Free State WT Cosgrave was shot dead in September in the family pub.

In October, in response to the Public Safety Act, the leader of the anti-Treaty forces said the army of the Free State was a legitimate target, as were politicians who voted for the act.

"The introduction by the Free State of legal execution is a consequence, rather than the initiation of, a cycle of violence that is still continuing," says Prof O'Halpin.

WT Cosgrave's uncle was among the victims of the Civil War

The fifth man executed - on 24 November - remains one of the most well-known.

Erskine Childers was born in England, educated at private school and Cambridge University and served in the British Army in the Boer War before becoming a committed supporter of Irish independence.

He was part of the Irish delegation that negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty with the British government but was strongly opposed to the final agreement and supported the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War.

He went on the run but was captured, tried by a military court on the charge of possessing a pistol, and executed.

His son went on to serve as president of Ireland in the 1970s.

His great-grandson, also called Erskine, says he believes he was "taken out over what he knew and was privy to, and the worry about how beautifully and sharply he could write it all down".

"Writers like Erskine are just impossible to ignore," he says.

He also believes there was an inevitability that once his grandfather was caught that he would be shot, following the first four executions of men aged between 18 and 21.

"Their lives were just ended on a technicality during a conflict. They were not military targets like Erskine certainly was," he says.

"After shooting teenagers to show that the government meant business, and to instil fear, why show mercy to someone they had spent seven months carefully destroying the character and reputation of?

"Executing Erskine was a gift to the WT Cosgrave government. He made it easy for them."

Mr Childers also argues that the full story of the executions can never be truly understood due to the destruction of documents.

At 52, Erskine Childers was the oldest man executed by the Irish Free State

Prof O'Halpin argues that as the executions continued the Civil War became "almost a social war" as the Free State leaders sought to "quieten the country down".

"They are very anxious that small fry, that young fellas, that undisciplined guys going around with guns be captured and executed as much as possible to put 'manners' on some people," he says.

"That's not a political thing - that's about social unrest.

"They use very strong language saying that the social order will collapse if we don't have more executions around the country."

The bitterness and trauma caused by the executions continues to resonate today.

Mr Childers says they are "internalized in Irish society, in our collective bloodstreams".

"There has been a culture of avoidance around unprocessed grief, which isn't helped further by a culture of selective remembrance," he says.

"In the last few years there's been professional levels of making sure the Irish public has their hands held tightly through contested history.

"We don't want anyone going to the library to read further into the history themselves because that's bad for business.

"My great-grandmother Molly wasn't allowed to mourn her dead husband for two years after his death."

By autumn and winter the Civil War had entered into a guerrilla phase, such as the bombing of this train in January 1923

Prof O'Halpin argues that on the political side of things the ramifications of the executions were not as long-lasting as might be expected.

"There is a lot of talk in Ireland around the commemoration of the bitterness of the Civil War - we have to look at other civil wars," he says.

"For example in August 1923 in Ireland the losers are allowed to take part in a general election - where else would something like that happen?

"I won't praise the Free State for that but I think it did lead to the rapid stabilisation of Irish politics.

"It didn't feel like it at the time but it led quite quickly to the acceptance of democratic norms."

Mr Childers says as the centenaries are marked, much pain remains for descendants of those executed.

"Many of the boys and men executed were the sole money earners for their entire families," he says.

"Family direct descendants to those executed that I've spoken with have conveyed awful stories.

"All I could say to some is: 'I hear and see you and I am angry with you.'

"At 100 years these families don't want a pity party - they want to been seen and heard, and, trust me, there is still pain."

- Published1 January 2022

- Published6 December 2021