Irish language: 'People have different reasons for wanting to learn'

- Published

Michelle Furey teaches students from "all backgrounds" and have various reasons for wanting to learn Irish

From building a connection with a family history to challenging the brain to think a little differently, there are many reasons why people choose to learn a new language.

Michelle Furey has heard many of those motivations given that she is teaching the Irish language to some 200 people from all around the world.

She runs online lessons for people in countries such as the United States, Canada, Argentina and Finland, as well as closer to home in the UK.

"Within the demographic of my classes we have people from all aspects of all communities and I am very much Irish for everybody," she says.

Michelle, from Plumbridge in County Tyrone, was working part time as an Irish teacher at a secondary school and running classes through her local council before the Covid pandemic.

But when lockdown hit she had to move her teaching online, allowing her to spread the word globally.

"I have quite a lot of expats who live in America but have Irish roots and want to preserve their links with home," she says.

"For the American audience it is definitely that they have traced their ancestry back to Ireland at some point and want to make a connection with their Irish roots.

"I have grandparents who have grandchildren going to gaelscoil (Irish language-medium school) and they want to be able to speak a little bit to them.

"I have people coming to me because they want to send their children to Irish-medium education and they don't speak any Irish."

Some students are taking the classes simply because they have an interest in learning languages.

"The lady who is from Argentina can speak four languages fluently," says Michelle.

The demand for her classes and the nature of online learning has meant her Irish language school has "reached a wider audience without really trying to reach a wider audience".

'It resonates with a lot of people'

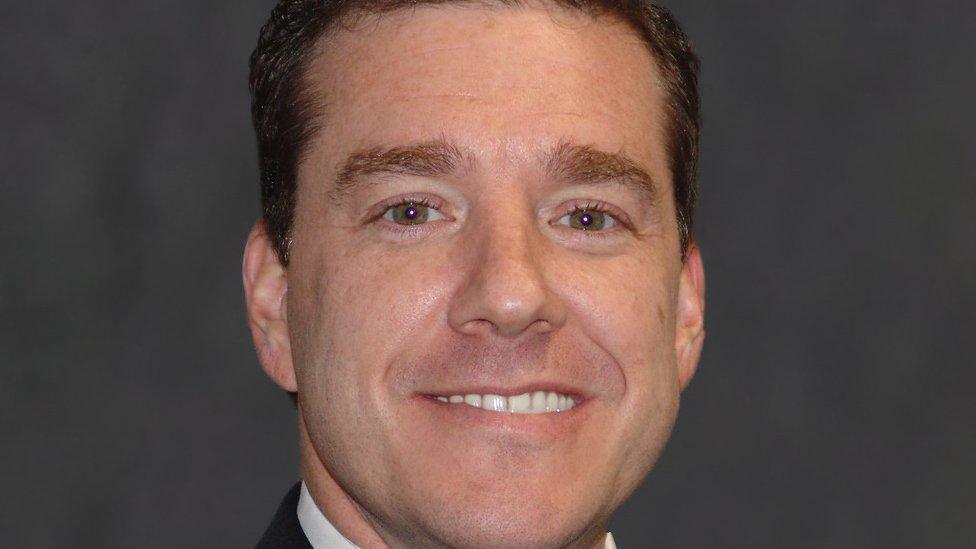

Rich Peppiatt has directed other films such as 'One Rogue Reporter' in 2014 starring Hugh Grant

London film director Rich Peppiatt started taking Michelle's classes two years ago.

He became interested in learning the language and was inspired to make a film in Irish after seeing Irish-speaking hip-hop group Kneecap from west Belfast perform in concert.

"There was maybe a thousand young people who understood every word of the Irish," he says.

"It surprised me because in my ignorance I always had this idea of the Irish language being quite rural, spoken by older people, and in an urban centre there were all these young people and it fascinated me."

Kneecap will feature in his film, which will go into production in Belfast early next year.

Mr Peppiatt, a former tabloid journalist who directed his first film One Rogue Reporter featuring Hugh Grant in 2014, says Irish language film is having a "real renaissance".

"It has always attracted less money than perhaps their English language counterparts because it is very niche.

"What Kneecap, for example, have done is they have taken something that could be very niche, like Irish hip-hop, and they tour around the UK, Europe and America and are finding big audiences.

"That just shows the Irish language isn't niche - there is a lot of people who it resonates with and there is a huge Irish diaspora around the world."

'I want to pass the language on'

Terence Farrell is Irish-American and proud of his roots

A large proportion of that diaspora can be found in the United States, where Terence Farrell was born.

He has Irish heritage on both sides of his family.

On his mother's side, his grandparents are from Lismore in County Waterford but they left there for New York in the 1920s.

The family roots on his father's side go back to County Leitrim before a move to America in the 1860s.

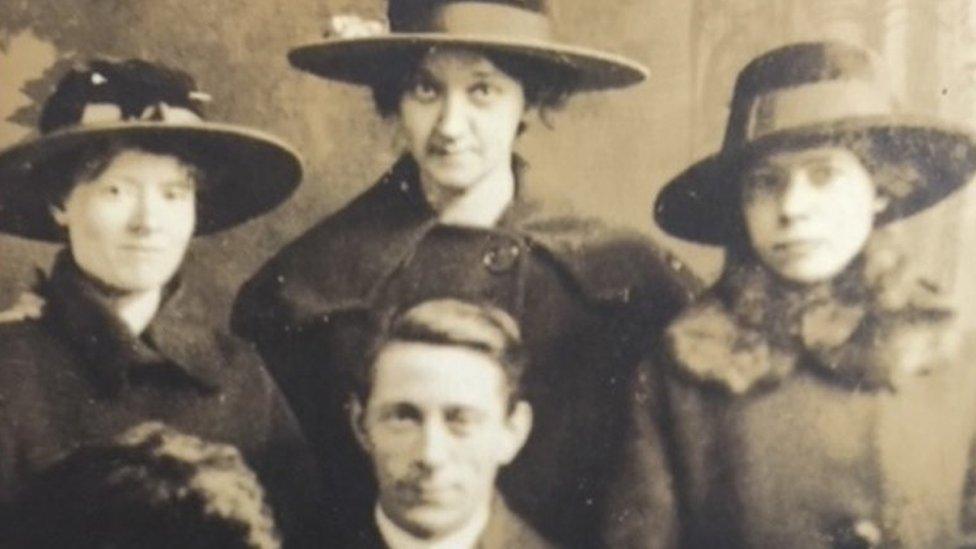

Pictured in 1923, Terence's maternal grandfather Henry Fenton, with his sisters Sheila and Mary and wife Anne Morrissey Fenton

When he was growing up Terence's maternal grandparents spoke Irish occasionally and he was taught how to say prayers in the language.

Terence, who lives in Oklahoma, became one of Michelle's students two years ago.

"It was of interest to me to be a part of how you maintain and how you grow the language so it doesn't get lost," he says.

"My children have learned the prayers that I knew and I want to be able to pass that on to their children as well, as much Irish as they can."

Terence's grandmother Anne spoke Irish

Terence visits Ireland frequently and even attended a gaelscoil in County Waterford last summer.

"I still have quite a bit of family who live in Lismore.

"One of my cousins still owns the house where my great grandparents were born so we can still make that connection."

'There's something special about it'

Jacqueline Beckett moved to Ireland after her retirement

Jacqueline Beckett never spoke Irish as she grew up in Buckinghamshire in England but discovered it in later life.

Her parents - both Irish - moved to England when they were teenagers and met each other there.

When Jacqueline retired to County Wexford she started learning the language and took Michelle's classes last year to help her become more integrated into her local community.

"You see [Irish] all the time - you see it on the signs," she says.

"It is part of the culture; You don't have access to if you don't have the language."

Now she speaks Irish daily with her neighbours and was recently involved in a project in which she spoke in Irish about the importance of the preservation of field names in the language.

It has given her a sense of connection to history.

"There is something special about being able to speak a language someone used to use all the time."

- Published30 October 2022