Northern Ireland Protocol: UK and EU remained at odds in 2022

- Published

The movement of goods between GB and NI and the checks needed for them continues to be a bone of contention between the UK and EU

Brexit's aftermath remained an open wound in Northern Ireland's politics and society in 2022.

Liz Truss was the third prime minister unable to heal it; Rishi Sunak will make his attempt in 2023.

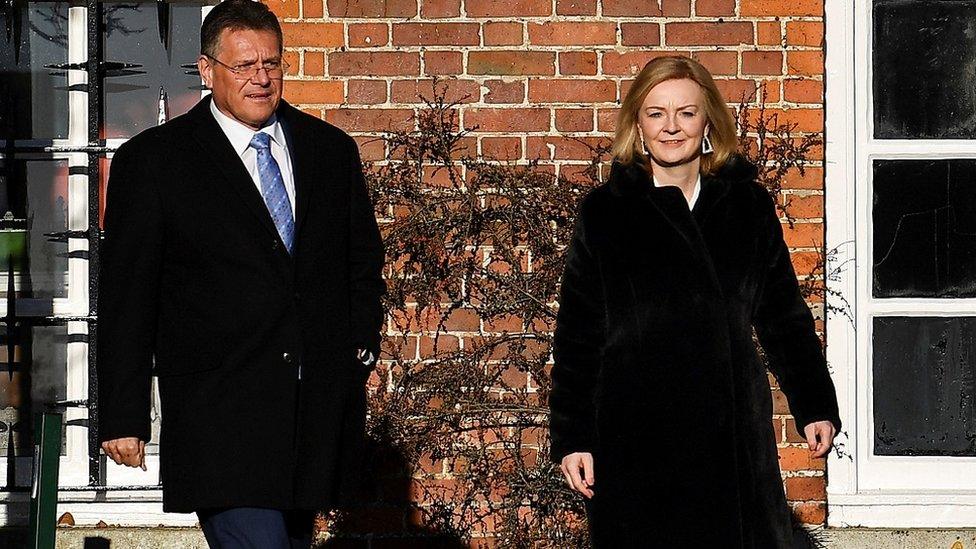

Ms Truss began the year as foreign secretary, inviting the EU's chief negotiator Maros Šefčovič to Chevening, the Foreign Office country mansion in Kent.

On the agenda: the protocol - Brexit's special form in Northern Ireland.

It was agreed by Boris Johnson in 2019 and keeps Northern Ireland inside the EU's single market for goods, so averting the need for checks at the Irish border.

But it means controls on goods entering Northern Ireland from Great Britain, which many unionists see as undermining their place in the UK.

Then Foreign Secretary Liz Truss with Maros Šefčovič in Kent last January

Throughout 2021, the UK and EU were increasingly at odds on how the protocol should be implemented.

Ms Truss's intention at the Chevening meeting was to draw a contrast with the combative style of her predecessor, Lord Frost, and reset relations with Mr Šefčovič.

It made for an Instagram-friendly stroll in sun-dappled grounds, but the better atmosphere could not be sustained, as fundamental differences remained.

The UK wants no checks or controls on products arriving from Great Britain that are destined to stay in Northern Ireland. The EU has offered to ease checks, but not eliminate them.

The UK wants to remove the European Court of Justice (ECJ) from its oversight role of the treaty. The EU says that's not possible, legally or politically, given the application of single market rules in Northern Ireland.

Any optimism about a potential breakthrough on these issues quickly drained away and by the spring relations deteriorated again.

Ms Truss had trashed EU reform proposals, originally made in October 2021, saying they would make things worse.

Her advisors were making clear she had grown frustrated with the EU and was instead planning domestic legislation to scrap parts of the protocol.

In those early months of 2022, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), Northern Ireland's main unionist party, had ramped up its opposition to the protocol.

In February, it withdrew Paul Givan from the first minister's role which automatically meant Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill, of Sinn Féin, lost her position.

In February, then Agriculture Minister Edwin Poots ordered officials to stop check on GB goods at NI ports

The remaining ministers were left in caretaker roles, unable to take big decisions.

The rules meant that by the end of 2022 ministers were gone entirely, leaving civil servants in charges.

In February, the DUP's Agriculture Minister Edwin Poots had also ordered officials at his department to stop checks on GB goods as they arrived at Northern Ireland's ports.

The checks continued as officials were concerned they had been given an unlawful instruction. Their fears were confirmed at the end of the year when the High Court quashed the order from Mr Poots.

The unionist campaign against the protocol also saw the continuation of legal action led by the TUV's Jim Allister.

That challenge to the protocol's lawfulness was rejected by the Court of Appeal in March and a final ruling from the Supreme Court is due in 2023.

Technical talks between the EU and UK were effectively suspended ahead of a Northern Ireland Assembly election in May.

Pro-protocol parties comfortably took the majority of seats with Sinn Féin returned as the largest party. The DUP remained the biggest unionist party and refused to end its protest.

In the aftermath of the vote, talks with the EU did not really resume.

Instead the UK government's focus was on legislation which set out a plan for sweeping powers to change the operation and oversight of the protocol.

The changes proposed in the Protocol Bill include the concept of green and red lanes for trade.

Trusted traders would use a green lane for GB goods that are destined only for Northern Ireland, meaning that would not need to be checked and would have minimal paperwork.

Goods destined to travel onwards to the Republic of Ireland would enter via a red lane, where they would be subject to standard EU controls and checks.

Alongside that is a plan for a dual regulatory regime, which would mean goods made to either EU or UK standard could be sold in Northern Ireland.

The bill is essentially a framework to empower the government to act, with the substance of these plans to be worked out later.

Among NI business groups there was broad support for the concept of green lanes, albeit with an acknowledgement that it would be better to have a solution agreed with the EU.

However, there has been resistance to the dual regulatory regime with some exporters arguing this would cut them out of EU supply chains.

The government also repeated its intention to water down the role of the ECJ and bring the oversight of the protocol "in line with international norms".

The reaction of the EU was predictable: "Let's call a spade, a spade," said Mr Šefčovic.

"This is illegal. It is extremely damaging to mutual trust and respect between EU and UK."

The response also included new legal actions aimed at earlier unilateral moves by the UK to ease the impact of the protocol,

Then taoiseach Micheál Martin (left) and new prime minister Rishi Sunak met in Blackpool in November and discussed the protocol

When Ms Truss won the Conservative leadership contest in September and became prime minister there was a fresh bout of optimism.

Technical talks between the UK and the EU restarted and the new Northern Ireland Office minister and arch Brexiteer Steve Baker acknowledged that he and others had not always acted in a way to inspire trust from the EU.

There was much speculation about whether or not Ms Truss' was shaping up to do a deal. But in the end that was academic as her premiership crashed and burned in spectacular fashion.

Under Mr Sunak, the technical talks and good vibes have continued but so far there is little public evidence that Downing Street is engaging intensively with this issue.

However, at some point soon Mr Sunak will have to show his hand.

Related topics

- Published25 October 2022

- Published2 February 2024

- Published15 June 2022

- Published11 February 2022

- Published15 June 2022

- Published13 June 2022