Mother-and-baby homes: 'One of the greatest scandals'

- Published

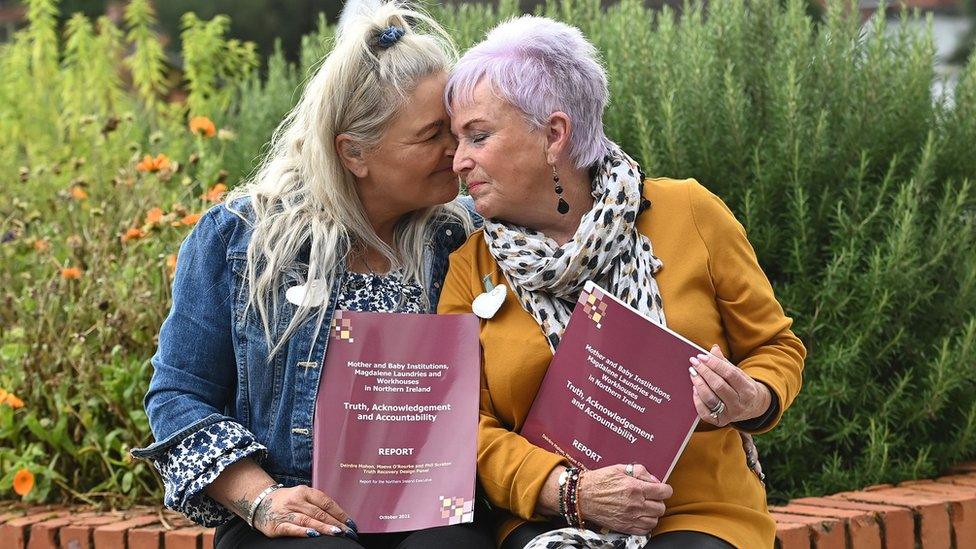

A Magdalene laundry in the Republic of Ireland

"The girls were seen as something to be dealt with - and we were the embodiment of their sin."

Mark McCollum was one of thousands of children born to unmarried mothers in Northern Ireland who were sent to institutions shrouded in shame.

His birth mother, Kathleen Maguire, was 21 years old when she became pregnant.

In the 1960s, having a child outside marriage was often regarded as morally taboo.

"It was part of a warped view of sexuality," he said.

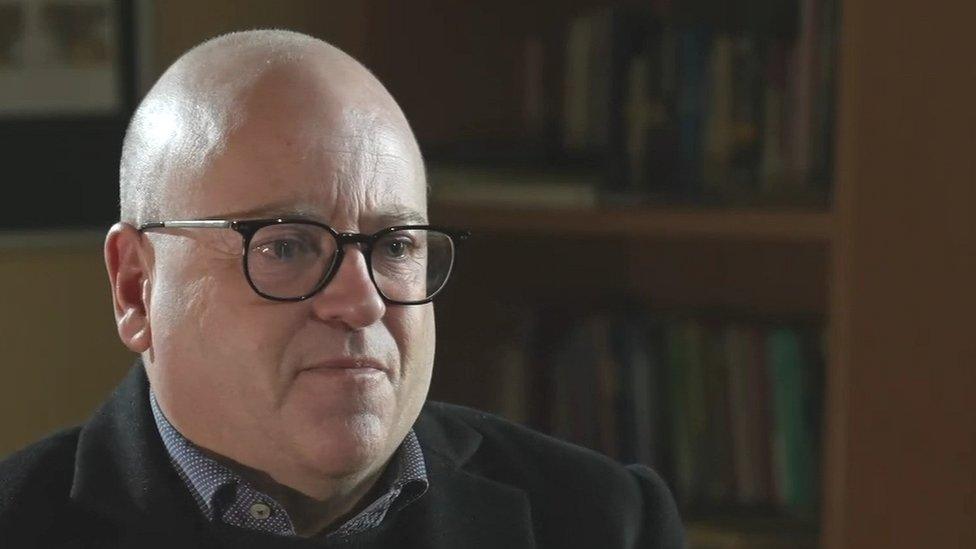

Mark McCollum traced his birth mother but it was too late and she died without meeting him again

Kathleen was sent to what was known as a "mother-and-baby home" - Marianvale, in Newry, County Down.

There were more than a dozen such institutions in Northern Ireland.

Three of them had workhouses known as Magdalene Laundries where women frequently had to do exhausting, unpaid labour.

On Mark's birth certificate, Kathleen's occupation is recorded as "laundry worker".

Mark has discovered that when he was a baby, he was driven by a social worker across the Irish border to a a children's home in Fahan, County Donegal. He was then adopted.

His adoptive family was "wonderful" - but he always wanted to know more about how his life began.

'The information came too late'

In recent years, he managed to find out who his birth mother was.

"She moved to Yorkshire, and got married but didn't have any more children. She died young - at the age of 54, in the year 2000," he said.

"It was bitter sweet - you finally had the information, but it had come too late."

A neighbour of Kathleen told Mark that his mother had looked for him - under the name she had given him, Paul Anthony Maguire. Mark said that she had been "thwarted from the other side".

"The whole system was set up to keep birth mothers and their children apart," he said.

Mark's mother, Kathleen Maguire, was sent to Marianvale home in Newry

Mark's experience highlights many of the questions which survivors of mother-and-baby homes want addressed by the state and the religious orders that ran the institutions.

One of the major issues is how babies were taken across the border to be adopted - which caused particular difficulties for Mark when he was trying to uncover details about his past.

"I have a birth certificate from Northern Ireland and an adoption certificate from the Republic of Ireland," he said.

"There was completely different legislation in each jurisdiction - but it didn't seem to matter.

"The church and state were complicit in this practice of cross-border adoptions."

Maria Arbuckle was taken the other way across the border - when she became pregnant at 18 years old.

Children who grew up in mother-and-baby homes urge politicians to press forward with public inquiry

She had spent most of her life in care until then - including 11 years with an abusive foster mother in Londonderry.

Maria went from an institution in County Armagh to St Patrick's Mother and Baby home in Dublin.

'So traumatic I blocked it out'

She has few memories of that time.

"Psychologists have told me it must have been so traumatic I've blocked it out," she said.

She does remember "sitting in a room typing all the time" and going to see her son.

"The nuns told me I couldn't cuddle or kiss him because he wasn't mine any more," she said.

When her son was almost 40 years old, she discovered that he was living in her original home city of Derry.

When they met, "the first person he saw was my sister, who he already knew - without realising she was his aunt".

Maria said her own childhood is evidence that the fostering and adoption system was open to abuse.

She said that the woman who fostered her came to the children's home "like she was going shopping" and asked for Maria and her brother "as if we were buy-one-get-one-free items".

All these issues are expected to be examined in an inquiry commissioned by the devolved government in Northern Ireland before it in effect collapsed in 2021.

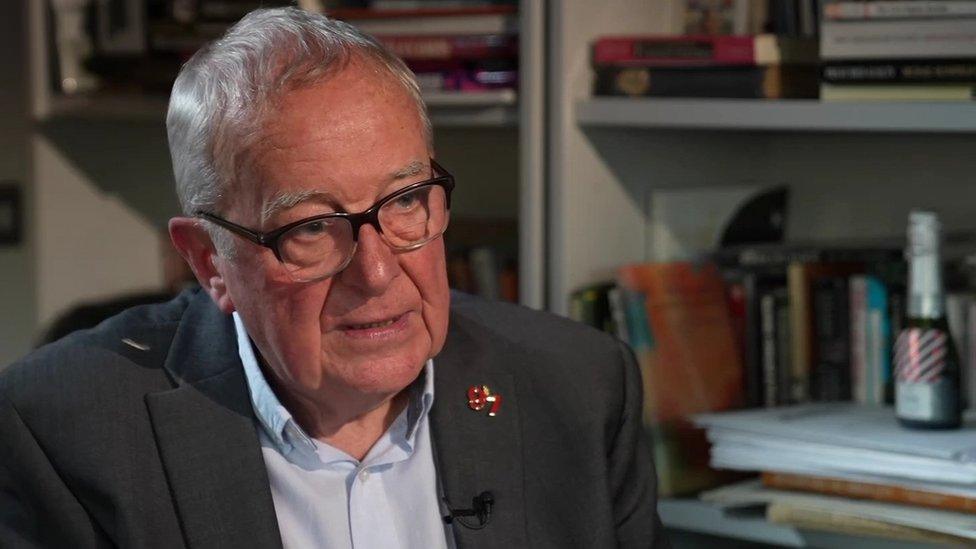

Prof Phil Scraton said taking children from their birth mothers was "one of the greatest scandals of our time"

The investigation was co-designed by survivors working with a group of experts, including Prof Phil Scraton from Queen's University Belfast.

The format draws on Prof Scraton's widely acknowledged work on inquiries into the Hillsborough football stadium disaster.

An independent panel will gather the stories of survivors in a non-confrontational manner and that evidence will feed into a public inquiry, where institutions and state agencies will be held to account.

"While some survivors will want to give evidence to a public inquiry, others would find it very intimidating," said Prof Scraton.

'I'm disappointed by the slowness'

He expects the ground-breaking model will become a template for other inquiries into similar issues across the world.

"The dovetailing of the information-gathering process with a full public inquiry is a unique way of making sure the voices of the most vulnerable are heard - and of getting to the truth."

The expert group which included Prof Scraton recommended that the independent panel should have been in place by March 2022 - but that has not happened yet.

"I'm disappointed by the slowness in the process," he said. "This is a fundamental issue of rights.

"The taking of children from their birth mothers is one of the greatest scandals of our time.

"Whether or not the Stormont Assembly is sitting, it is absolutely essential that as soon as the independent panel is doing its work, the next phase should be in process - it was always designed to be overlapping."

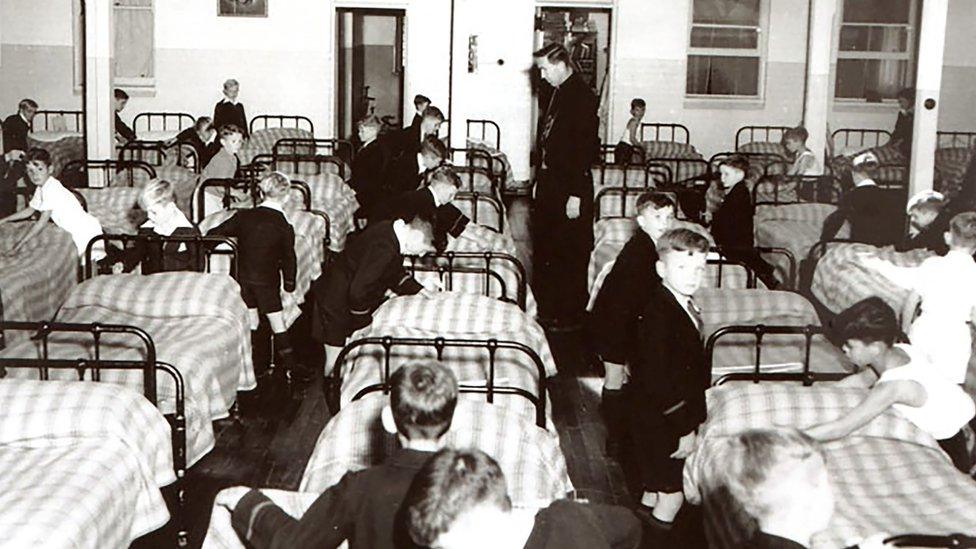

Children from a home in the Republic of Ireland

Mark McCollum said movement with the inquiry had been "painfully slow". He is calling for politicians to "push things forward".

"If momentum can't come from Stormont, it has to come from Westminster," he said.

The Executive Office at Stormont - which will be headed by the first and deputy first ministers if and when the devolved government returns - said "significant progress" had been made, and the independent panel is being recruited to begin work in early 2023.

Legislation on the public inquiry and a redress scheme is also being prepared.

The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission is supporting survivors' desire for justice and redress, saying in its 2022 annual statement that "the historical abuse of children and adults continues to raise grave violations".

A separate police investigation is being conducted by specialist officers.

'We are not rushing'

So far, 80 survivors have reported alleged crimes - mostly illegal adoptions.

Detective Superintendent Gary Reid said his team are trained to help people make statements about such personal matters.

"We are not rushing - we are here for people when they are ready to speak to us," he said.

Det Supt Reid said there is a dedicated phoneline and email address - 028 90901728 and motherbabyhomes.magdalenelaundries@psni.police.uk - for information and that the police will take what people have to say seriously.

While survivors may have various perspectives on how they would like the abuses of the past to be dealt with, almost all mention a desire for accountability.

"When I write my book, it'll be called 'I was born to be neglected'," said Maria Arbuckle.

"That was by every authority figure that came into my life. They need to hold up their hands and say that should never have happened."

Related topics

- Published15 November 2021

- Published5 October 2021

- Published27 September 2022