Purse strings tighten across Northern Ireland

- Published

MLAs have had 700 reasons to be distracted this week after the PSNI's chief constable delivered dramatic news about policing cuts.

That is because they were grappling with their own budget concerns having received their monthly salary on Friday - minus £700.

It was the first bite in the MLA wage cut imposed by the Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris.

Now, instead of taking home around £3,100 a month, MLAs will have to survive on about £2,400.

They, like Chief Constable Simon Byrne, have now been forced to adjust their expenditure to take stock of a new budget reality.

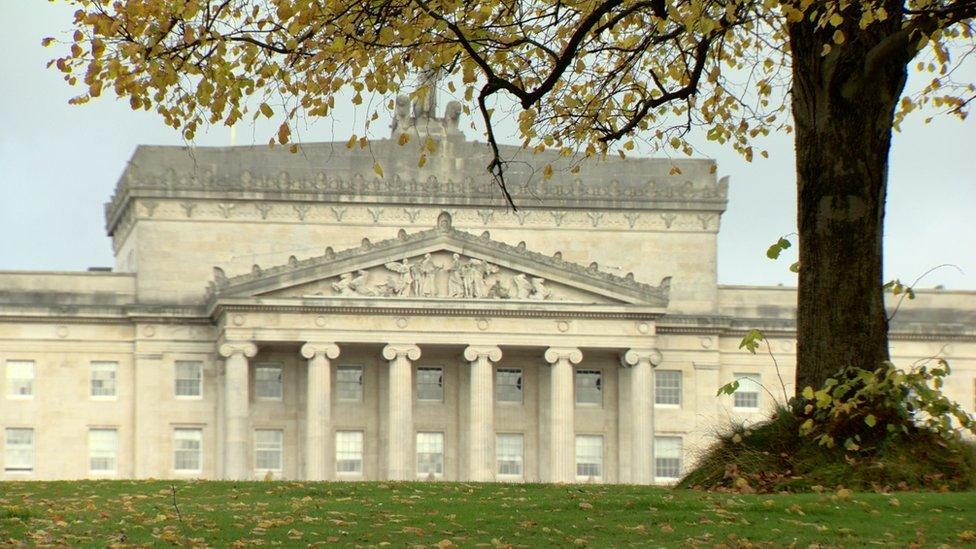

Unlike Mr Byrne though, the squeeze on MLAs' finances could end quickly if the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) returned to the executive and Stormont was restored.

A quick remedy for the chief constable is less likely because of the dire state of Northern Ireland's balance sheet - thanks in no small part to the absence of those same MLAs from Stormont because of the DUP stand-off over the Northern Ireland Protocol.

For the past year, Northern Ireland has been trapped in a political straightjacket at a time when so many economic levers needed to be pulled.

So how did we fall into such an economic mess which has caused such chaos in health, education and policing?

How will the only political hand left on the lever - Mr Heaton-Harris - steer Northern Ireland through this crisis?

Chris Heaton-Harris is expected to signal the big cuts which will be needed once an executive is restored.

Having no agreed budget at the time the DUP pulled down the institutions last February meant there was no spending control in place when ministers returned in a caretaker capacity after the assembly election in May.

Around the same time the treasury turned off the funding tap for the regions post-Covid and the ability to re-allocate unspent money between departments was lost when monitoring rounds disappeared with the other Stormont structures.

Instead, what we had were ministers making spending decisions based on what they felt would have been agreeable had an executive been in place.

That 'blind spending' ultimately left a £660m overspend hole in the finances.

About £500m of that was directly linked to soaring energy costs of £200m and the rest was blamed on increased public service pay pressure.

To plug the hole, the treasury agreed to an advance payment of £330m from next year's budget which heaps more pressure on an already strained financial outlook.

As things stand, Stormont departments will have to make cuts totalling £500m and that figure could easily rise to £1bn when you factor in inflation and extra pay pressures post the public sector strikes.

The cuts are already starting to bite for the PSNI with savings of £80m to be made before the end of March and a warning from the chief constable of more pain to come as he prepares to shrink the service over the next three years.

The cuts are already starting to bite for the PSNI with savings of £80m to be made before the end of March

In health, the Permanent Secretary Peter May recently warned of difficult decisions because of budget uncertainty.

Hospitals and GP practices are already working beyond capacity at a time when waiting lists remain the highest in the UK.

Health can expect to get at least 51% of next year's £14bn budget, but even that will fall far short of what is needed to fix the deep-seated problems and put the much needed plans in place for transforming the health service.

In education, the authorities have been asked to identify 10% in cuts from the £2.4bn it is likely to get in the 2023/24 budget.

Though that, we are told, is a scoping exercise and no final decision has been made.

The Education Authority (EA) has already refused to make £110m in savings before the end of this financial year as it would require cutting frontline services.

EA board member Mervyn Storey told BBC News NI's The View the shortfall could rise to £500m by April.

With 80% of the education budget spent on staff, extra support for special needs children could suffer.

Water charges?

So, what are the chances of cuts being imposed by civil servants without political cover?

The answer is "unlikely", according to Peter May who said he was reluctant to "overreach".

And we have been told not to expect much interference from the secretary of state.

Instead, we can expect Mr Heaton-Harris to simply signal the big cuts which will be needed once an executive is restored.

"The scale of the problem requires something more fundamental than tweaking, but tweaking is all we are likely to get," said one source.

"Small percentages being shaved off departmental budgets based on the trajectory left by the outgoing ministers," they added.

But revenue raising measures like introducing water charges are being considered by the secretary of state to ease the financial burden.

Water charges could be considered as a means of raising revenue

He is also due to set a regional rate within weeks with some speculating an increase of more than 10%.

But increasing the regional rate by this amount would raise between £30m to £40m which, considering the impact such a hike would have on ratepayers, it may be a step too far.

As much as Mr Heaton-Harris would like to use economic pressure to try and force the DUP back into Stormont, he cannot afford to punish those already struggling in a cost of living crisis.

Instead, he will hope the protocol talks deliver and the executive is restored. If not he may have to take another slice of MLAs' pay.

In the unlikely scenario Stormont returns, history tells us there could be a big financial sweetener to ease the budget pressure.

Given what awaits them, do not be surprised if ministers refuse to go back without it.

Related topics

- Published3 December 2022