NI Troubles: 'I would love to see that wall coming down'

- Published

Michelle Bradley (left) and Lily Brannon (right) live either side of the Springfield Road peace wall

Michelle Bradley and Lily Brannon are neighbours separated by a wall of one million bricks.

The two friends live either side of one the longest peace lines in Belfast and 2023 was meant to be the year by which it was no longer needed.

"In an ideal world I would love to see that wall coming down," says Lily.

Michelle nods in agreement, before adding a dose of reality: "That wall stops the rioting and means we can live in our street in peace."

In 2013, Stormont's Executive Office launched a headline-grabbing plan: the removal or reduction of all peace lines in a decade.

In 2023, about 60 remain, scattered mostly across Belfast, but with one or two others in Londonderry and Portadown.

Mr McGuinness said the plans would be a decisive step forward to uniting the community

At the outset of the Troubles in 1969 they were easy to build - often starting as barbed wire fences erected by the Army.

But 25 years after the Good Friday Agreement they are proving difficult to bring down.

The peace line at Cupar Way, between the Shankill and the Falls areas stands 14m (45ft) tall - that is three times the height of the former Berlin Wall and it has been in place twice as long.

"They were built as quick ways to alleviate violence and disorder," according to Dr Johnny Byrne, an Ulster University academic who has researched peace walls.

Johnny Byrne said peace walls had become a symbol of the peace process

"You can't guarantee that if they came down violence won't start.

"They have become a symbol of the peace process in a negative way in terms of what still needs to be done."

The Department of Justice (DoJ) is responsible for about 40 structures and the Northern Ireland Housing Executive a further 20.

The DoJ said 18 peace lines had been removed over the past decade.

A similar number have been reduced in size or modified - including gates at Flax Street in north Belfast which replaced a barricade that closed the road for 40 years.

Traffic and people now move freely.

Gates have replaced a barricade at Flax Street in north Belfast

The DoJ said nothing happened without the agreement of local communities and a security assessment, but negotiations were often protracted.

"It took almost 11 years of conversations to change the structure at Flax Street," said Ian McLaughlin, of the Lower Shankill Community Association.

"The executive initiative was welcome but government did the wrong thing by putting a timeline on what they expected to happen.

"In many ways it created fear."

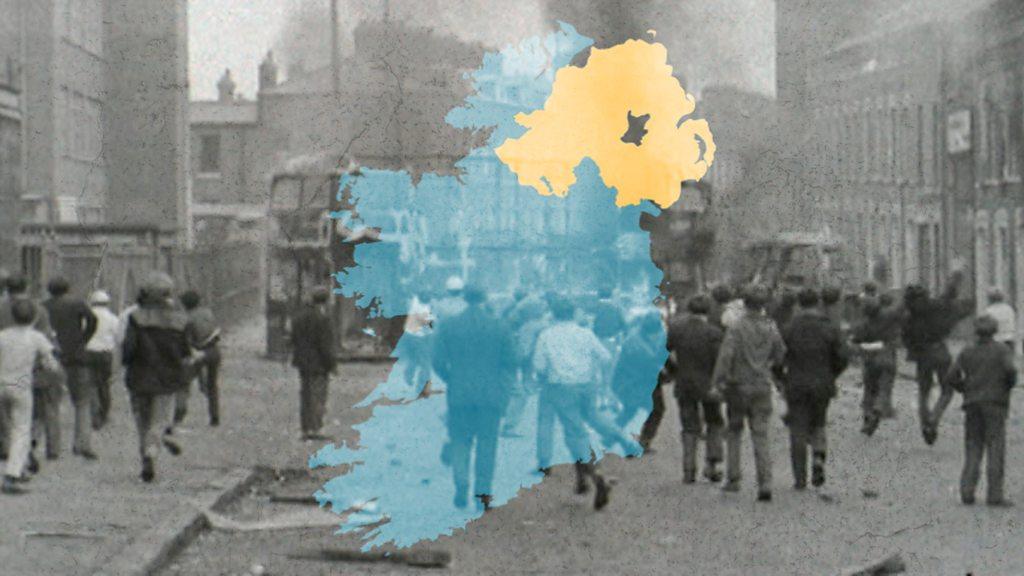

The roots of Northern Ireland’s Troubles lie deep in Irish history

The majority of peace lines are in areas which witnessed some of the worst violence of nearly 30 years of conflict and mental scars remain, according to the International Fund for Ireland.

Financed by overseas governments, the fund supports a number of community organisations engaged in peace line initiatives.

Paddy Harte says trauma remains in Northern Ireland's divided communities

Its chairperson, Paddy Harte, said: "I think we have come quite a long way in 2023 given the distance that people have had to travel."

"People should be very proud of how far they've come given the trauma that is still there."

'To keep the peace'

Michelle and Lily live in houses which look out onto opposite sides of the Springfield Road peace wall.

Both are involved with the Black Mountain Shared Space group.

Lily said: "If that wall came down I would get a lovely view across the road and I'd be able to nip into Michelle's for a cup of tea.

"But it's there for a reason. To keep the peace."

Michelle added the wall has not stopped cross-community engagement: "We discuss these things. There's nothing off the table."

"Everything is spoken about in our group," she continued.

"A united Ireland or should we stay a part of the union?

"We had a Christmas market at the bottom of the street and two communities came together and had a beautiful day.

"Although there's a physical barrier I don't think the community barrier is as big as it was."

Watch Julian's peace lines report for BBC Northern Ireland's The View on iPlayer.

Related topics

- Published29 January 2020

- Published13 August 2019

- Published16 April 2021