Good Friday Agreement: The battles and big calls on the road to peace

- Published

The remnants of a car bomb explosion in Portadown in February 1998

It is almost 25 years since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the peace deal that brought an end to the Troubles - in the coming weeks, BBC News NI across our news website, TV and radio, will be looking back at the historic deal, speaking to the key players and reflecting on how the agreement continues to shape Northern Ireland.

Former BBC News NI security correspondent Brian Rowan reported on all the major moves leading up to the deal and beyond - here, he looks back on how paramilitary violence threatened to scupper the talks long before agreement was in sight.

There is no such thing as a straight road to peace.

And now, 25 years beyond the historic events of 1998, we have a better understanding of the challenges - or even, at times, the hell - of that period.

The lead up to the agreement on 10 April 1998 was not just negotiations and talks - there were killings, bombs, internal battles and big calls to be made, which would have huge political implications.

Take this day, 25 years ago - 20 February 1998. The day that Sinn Féin was suspended from the peace talks.

At the same time, one of the loyalist parties, the Ulster Democratic Party (UDP), the political wing of the the loyalist paramilitary group, Ulster Defence Association (UDA), was told it could return to the negotiations, having left a month earlier.

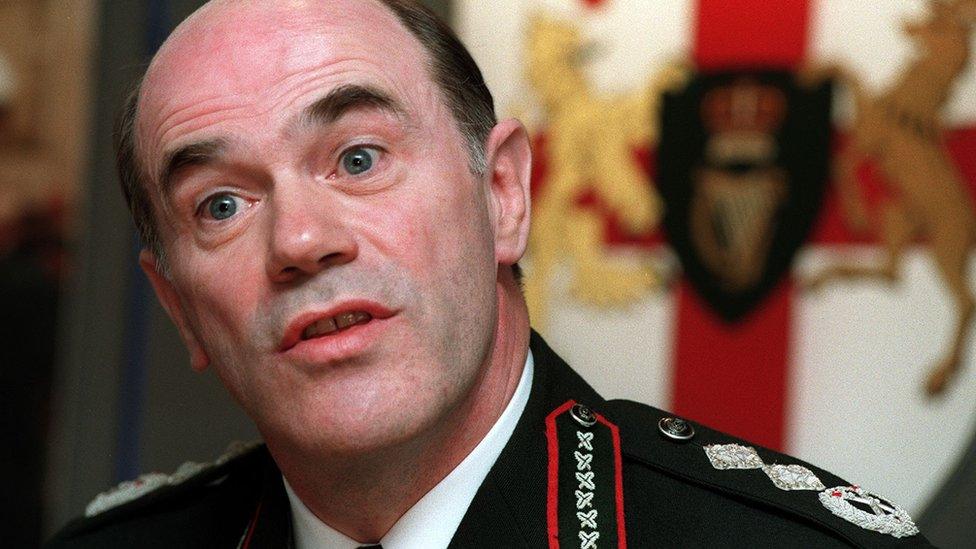

Sir Ronnie Flanagan, then Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) chief constable, was a central figure in those decisions.

Sir Ronnie Flanagan emerged as one of the most important leaders in the evolving peace

It was his assessment that both the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), a cover name for the UDA, and the IRA were involved in a number of killings, at a time when both were supposed to be observing ceasefires.

When Flanagan made his assessment known to Secretary of State Mo Mowlam, we witnessed a talks crisis in real time - first the UDP and then Sinn Féin were told to leave the negotiations.

Both would be back inside the room before agreement was reached, but in those days and weeks the headlines suggested the very opposite of hope and compromise.

Good Friday Agreement: Ronnie Flanagan on the big calls on the road to peace

When asked if he believed those interventions brought the killings to some end - and made the UFF and IRA think again - he replied: "I do think that. I think they thought the game was up - 'we can't engage in this subterfuge. We can't carry on this utter criminality and pretend it's someone else.'

"So I think, to that extent, it was an inhibiting factor for them to carry on in that dishonest way."

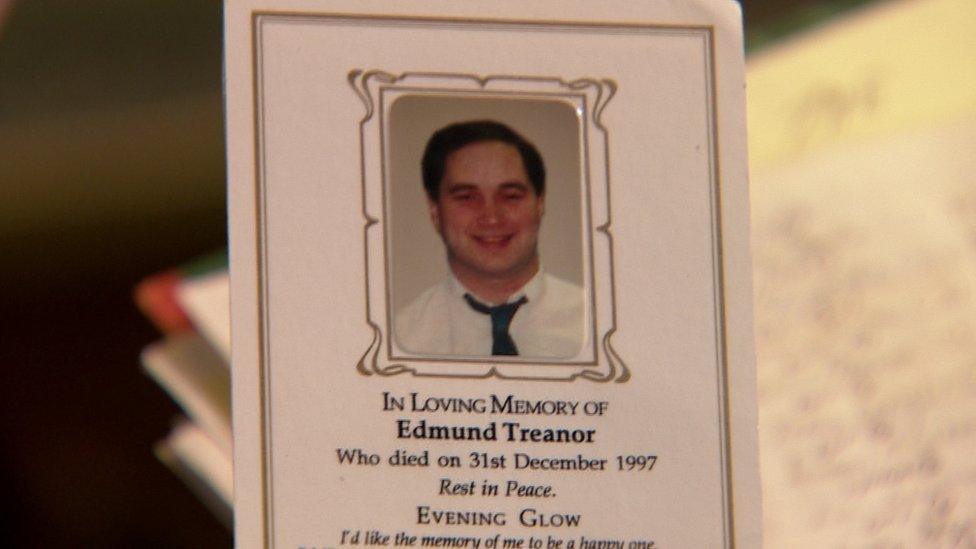

Eddie Treanor was killed by the UFF in December 1997 - one of three killings that led to the UDP exiting peace talks in February

Battles inside the IRA

At that same critical time, internal battles were raging inside the republican movement - or "the difficult struggle", as Flanagan described it, that Sinn Féin leaders Gerry Adams and the late Martin McGuinness had in trying to hold "the critical mass of their organisation behind them".

Just months before Good Friday, they had survived an attempted coup - a battle inside a so-called IRA convention, which elects the leadership and decides policy.

There were dissidents who did not want to follow the road to peace.

Some of them were among the most senior IRA figures in charge of armaments and developing weaponry. They resigned from the IRA in late 1997.

I remember, in January 1998, noting a statement from the IRA that, in angry words, rejected a significant draft paper introduced into the political talks.

Weeks later, just when Sinn Féin was being expelled from the talks, bombs exploded in Moira and Portadown, in the parliamentary constituencies of unionist MPs Jeffrey Donaldson and David Trimble.

Good Friday Agreement: Martin McGuinness "saw more progress in politics"

It looked like the IRA: it felt like the IRA. Trimble spoke of that organisation "venting its spleen". But this was the dissident republican paramilitaries entering the scene and making their opposition to the direction of peace talks known.

The IRA was forced to explain itself.

Timeline: 1998's crucial early months

A worker clearing debris in the aftermath of a car bomb in Moira, County Down, in February 1998

22 January 1998: RUC Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan says the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), a cover name for the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), was behind the killings of three Catholics in recent weeks - Eddie Treanor, Larry Brennan and Ben Hughes - despite being on a ceasefire.

26 January: The Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) leaves the peace talks and is suspended from returning unless the UFF maintains its ceasefire.

12 February: The IRA releases a statement saying its ceasefire is intact after the killings of Brendan Campbell and Robert Dougan, both shot dead in recent days.

20 February: Sinn Fein is expelled from talks due to allegations of IRA involvement in the two killings. The party will not return for more than a month; on the same day, a car bomb explodes in Moira, County Down, near the town's police station.

23 February: A car bomb explodes in Portadown, County Armagh. The IRA denies involvement in both attacks, with dissident republicans thought to be to blame.

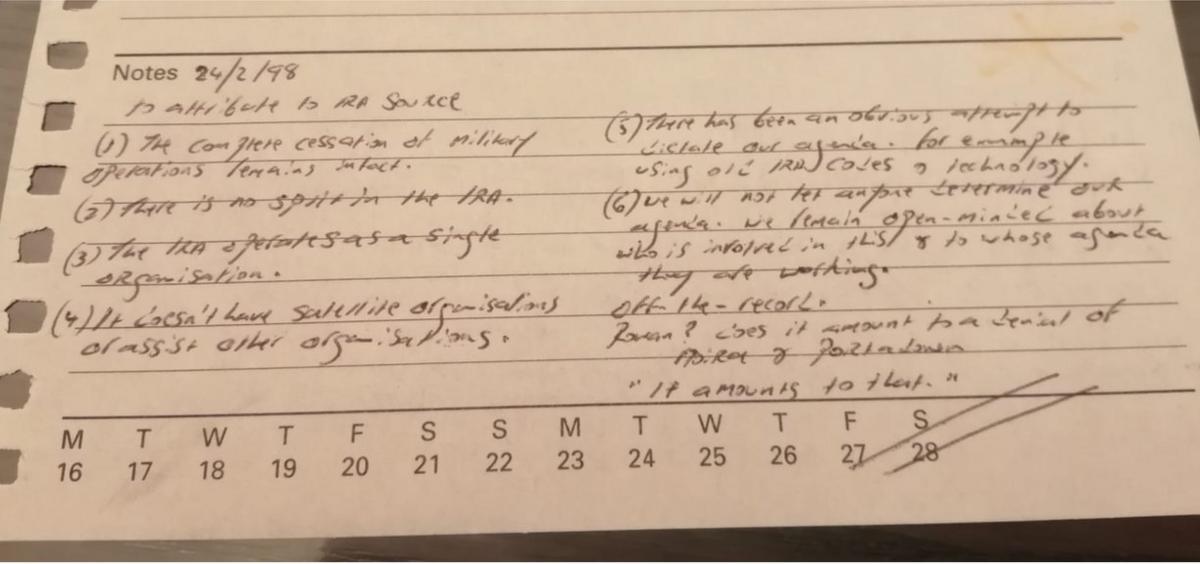

On 24 February 1998, I met its spokesman and, later, copied the note of that briefing into my diary.

I was told: "The complete cessation of military operations remains intact; there is no split in the IRA; the IRA operates as a single organisation; it doesn't have satellite organisations or assist other organisations…

"We will not let anyone determine our agenda…"

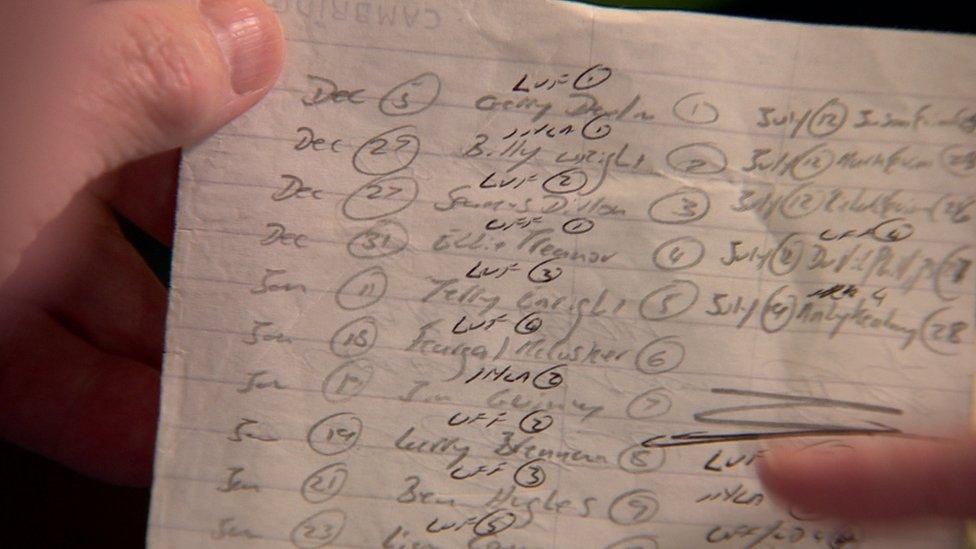

The author's notes of an IRA briefing given to him in February 1998

So for guidance, I asked, did the briefing amount to a denial of involvement in the Moira and Portadown bombs?

"It amounts to that," came the reply.

There had been a fracture inside the IRA resulting from that convention in late 1997 and those who left had the capability to pose a serious threat.

Sir Ronnie recalled: "There were prominent people, people who knew where the armaments were; people who'd been involved throughout who didn't think this was the desired end of the campaign of violence they had engaged in."

Jake Mac Siacais was a senior and influential republican figure during my reporting of the conflict period - he left the movement after that 1997 convention, not to join the dissidents, but to go home. His "war" was over.

For him, the dissident threat was very real.

Good Friday Agreement: 'Adams-McGuinness carried off almost the impossible'

"Had they been able to muster enough strength internally within the IRA, there was a real possibility that republicans would have feuded, would have shot each other.

"They didn't gain sufficient strength. They went on to make a number of huge logistical and strategic and political blunders, which really brought them to an end… the Omagh bomb being one."

Imperfect peace

In that fog of 1998, I couldn't see the possibility of a peace agreement emerging.

There was too much else going on - the shootings, the bombings, the rubble, the statements, the briefings; other big issues emerging in the frame, such as prisoner releases and police reform, as well as questions about guns and decommissioning.

The author's handwritten notes on killings that took place in in late 1997 and early 1998

Flanagan, seeing the intelligence information, had a better vision of possibilities.

He would later manage the Royal Ulster Constabulary through a painful period of change, with its name going in favour of a new beginning as the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI).

That was one of his major contributions in that transition from conflict into today's imperfect peace.

"Many people are alive who otherwise, sadly, would have lost their lives," he told me.

"So, it is imperfect," he continued. "There's still much more to be done, but we're in a much better place."

This is his summary of where we are; better than where we were.

But, he is right. There is still much to do - perhaps the biggest task is how to find a process and a way to answer the questions from a past that still speaks loudly in the present.

Related topics

- Published3 April 2023