Brexit: What is the Stormont brake?

- Published

Watch: How would the Stormont brake work?

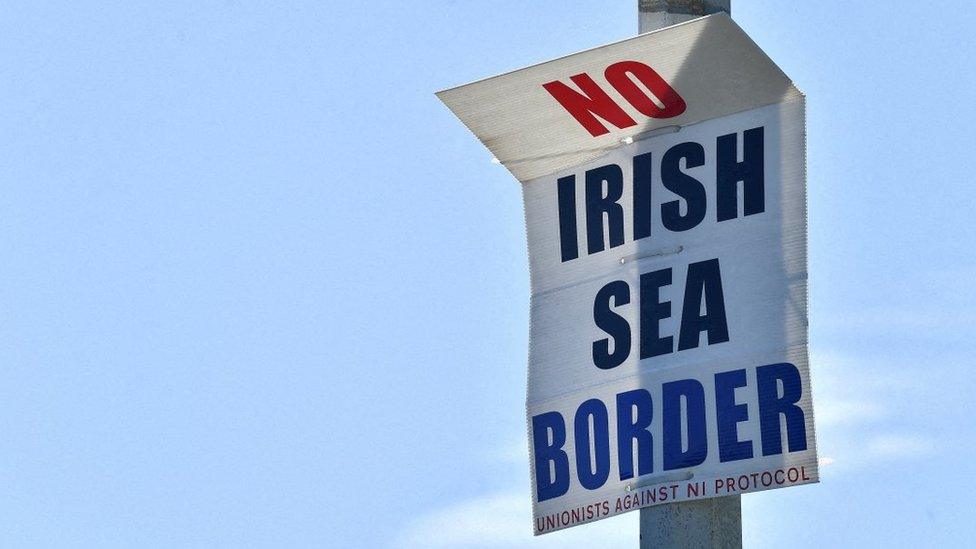

First came the backstop, then the protocol, now we can expect to hear a lot more about the "Stormont brake" as it is added to the Brexit lexicon.

But could the aforementioned brake being hailed by Rishi Sunak in his new Brexit deal end the year-long break in devolved government in Northern Ireland?

The plan aims to give a future Northern Ireland Assembly a greater say on how EU laws apply to Northern Ireland - a key demand of the Democratic Unionist Party's before it will end its boycott of power-sharing.

Why is the UK government introducing this?

Under the protocol agreed by the UK and EU back in 2019, some EU laws on goods and customs apply in Northern Ireland but politicians at Stormont had no formal way to influence those rules.

They, as well as some businesses, had been calling for a wider consultative role - something that had been ruled out under Boris Johnson's administration.

AT-A-GLANCE: See just the key points of the deal

ANALYSIS: John Campbell takes a look at what it means for business

DUP DILEMMA: Stakes could not be higher over Brexit deal

The new deal introduces a mechanism to allow elected representatives in the Northern Ireland Assembly to raise an objection to a new goods rule.

How would they do that?

According to the government it involves a variation of a well-run and at times controversial Stormont tool known as the petition of concern.

It is a safeguard procedure agreed as part of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, originally designed to protect the rights of minorities.

The brake involves a variation of a Stormont tool known as the petition of concern

A petition of concern normally requires the signatures of 30 MLAs (members of the legislative assembly) from two or more parties, meaning an issue would then be subject to a cross-community vote requiring a majority of unionists and nationalists, before it could proceed in the assembly.

But critics said its terms over time effectively amounted to a veto for larger parties and it was reformed in 2020 to restrict its use.

In this case, the government has decided only one part of that process needs to be used by MLAs to flag up their concerns to London about a new EU goods rule coming into effect.

So how would it work?

It requires 30 signatures - that threshold allows unionists alone to object to regulations.

There are 35 MLAs from unionist parties in the current assembly and two independent MLAs who designate as unionist.

Once that happens, it goes directly to the Westminster government for consideration - a cross-community vote is not required.

When the UK has intervened, the EU law in question would automatically be suspended within a maximum period of four weeks, ahead of further independent arbitration with the EU via the Joint Committee, which oversees the operation of the protocol.

The government's command paper states that this provides Stormont with a "genuine and powerful role" in the decisions about the application of EU laws in Northern Ireland.

Crucially, it can only work once there is a fully-functioning executive and assembly at Stormont.

Are there other conditions attached?

Yes - while the UK says it is doing this unilaterally to address the "democratic deficit" caused by the current consent arrangements, the EU has also made clear it views this as an emergency brake.

It says the measure can only be used in the "most exceptional circumstances and as a matter of last resort".

Watch: Key moments from the PM's NI Brexit deal speech

The government states the mechanism cannot be used for "trivial" reasons and that there will need to be a clear demonstration that an EU goods rule being challenged is having a "significant" impact on everyday life in Northern Ireland.

In addition, the government says the burden of proof for that will lie with MLAs, to be provided in a "detailed and publicly available written explanation".

The government expects there to be a consultative process first.

And the EU would also be able to counter the move with any remedial action it sees fit, raising the prospect of a potential future stand-off.

Would Stormont get a vote?

The Northern Ireland Assembly sitting in January 2020

That would not be required to trigger the brake, but it has been suggested as a possible way of releasing the brake.

The government says a decision on whether to permanently block an EU rule, once suspended and following discussion in the Joint Committee, would not happen "in the absence of a cross-community vote".

The process has yet to be worked out fully and will require consultation with the Stormont parties.

It would also mean legislation is needed to amend the Northern Ireland Act 1998, legislation that established the current governance structure at Stormont.

There are also additional caveats.

The government says it could still demonstrate "exceptional circumstances" to justify imposing the new rule, even if a vote at Stormont made clear its opposition.

DUP former deputy leader Lord Dodds has been critical of this, saying it means Stormont will not "have the final say" on such matters.

Could the DUP back the plan?

The DUP will want to look beyond the headlines and study the legal text

The Stormont brake is just one part of the new agreement - albeit a very big part and one Rishi Sunak is keen to promote.

Some in government say the DUP should chalk this up as a win when after all, it is among the party's seven tests for a deal.

The DUP leader's initial reaction on Monday gave little away but Sir Jeffrey Donaldson left himself room for manoeuvre.

Securing the DUP's backing will depend on how the final legal text stacks up with what has so far only been outlined in slim detail.

Other Stormont parties have expressed reservations about the proposal saying they remain unclear about what it will actually require, and believe it could be too powerful a tool handed to unionist parties.

- Published2 February 2024

- Published28 February 2023

- Published28 February 2023