Good Friday Agreement: Northern Ireland, peace and women

- Published

In 2000, just two women, Brid Rodgers from the SDLP (in red jacket) and Bairbre de Brún from Sinn Féin (in navy jacket), sat in Northern Ireland's cabinet

"It's not that women get written out of history - they never get written in".

The words of Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, who became the youngest woman elected to Westminster in 1969.

And to many the defining picture of the Good Friday Agreement is of two men signing a piece of paper.

But that image was decades in the making - a complex process led by both men and women.

Prof Yvonne Galligan, from Technological University Dublin, says women's contribution to the peace process must not be sidelined.

"Everybody needs to remember Mo Mowlam, the role of the Women's Coalition and that there were other women from political parties at the table," she said.

Then prime minister Tony Blair (left) and then Taoiseach Bertie Ahern signing the Good Friday peace agreement

Currently women are more prominent than ever in Northern Ireland politics.

Mary Lou McDonald and Michelle O'Neill lead Sinn Féin and Naomi Long heads the Alliance Party.

Arlene Foster was the first woman to become Northern Ireland first minister when she was leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

But if you turn the clock back 25 years the landscape looked very different.

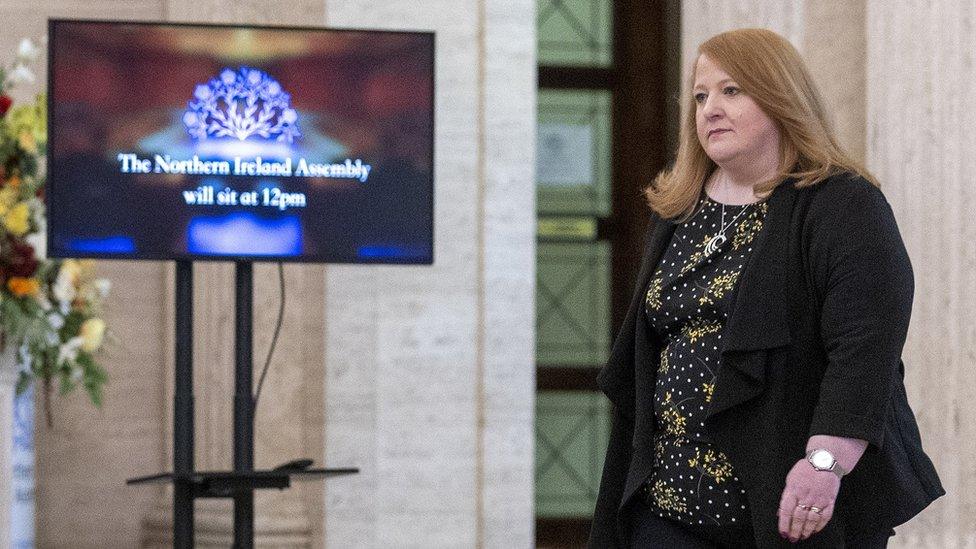

Naomi Long has been leader of the Alliance Party since 2016

Women had been involved in many peace efforts building up to the talks and negotiations in the 1990s - many of which were within local communities.

But when it came to politics the number of women there did not reflect society.

In 1996, when 110 people were elected in to take part in multi-party talks at Stormont, only 15 were women.

Women and the path to peace

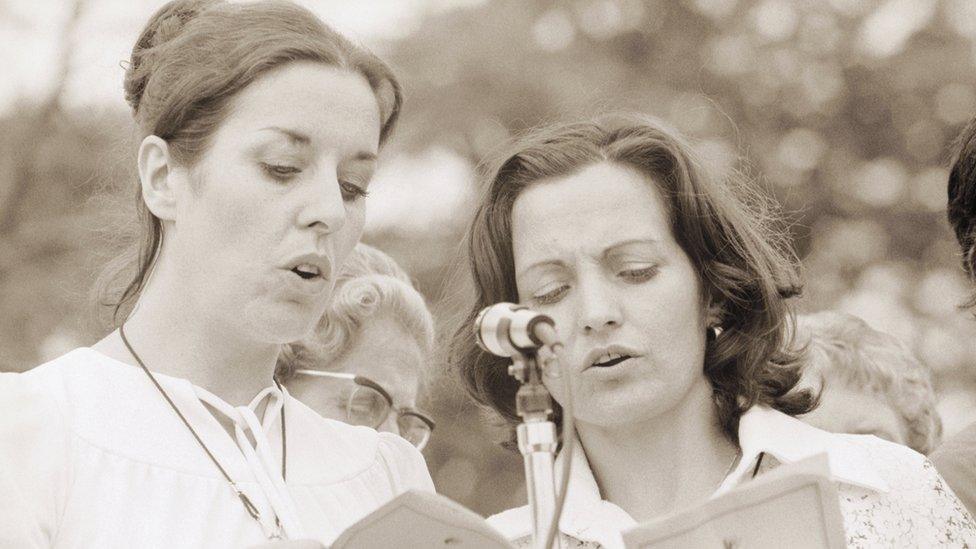

Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan recite the Peace Pledge to thousands of supporters in Woodvale Park.

In the 1970s two women, Mairead Corrigan Maguire and the late Betty Williams, gained political prominence for their cross-community work and were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Trade union leaders like Inez McCormack and Baroness May Blood, who later joined the Women's Coalition, campaigned for social change before moving into politics.

Former Alliance Party deputy leader and Assembly Speaker Eileen Bell started a number of cross-community youth groups in Belfast before entering politics.

"I think women in politics always bring a different way of speaking and thinking about what was happening," she told the BBC's Ireland correspondent Chris Page.

"When they make the decision to come in to the political arena they do come in with a completely different perspective."

Eileen Bell, seen here in 2003 with Tony Blair, Peter Hain and Bertie Ahern, said women may not always get the credit they deserve

Bríd Rodgers, a former SDLP MLA and a prominent figure in the peace talks, said women had been key in driving social change in Northern Ireland during the 1960s civil rights movement.

"It was the beginning of people recognising that the way forward was peaceful and not through violence," she said.

"There were women like Edwina Stewart - a teacher from east Belfast who lost her job because of her position - who stood up to be counted."

The forum, the negotiations and misogyny

Belfast social worker Pearl Sagar founded the NI Women's Coalition with Monica McWilliams

The cross-community Women's Coalition was a unique party.

"We came from people who identified as British, Irish, both, or neither," co-founder Monica McWilliams told the BBC's Ireland correspondent Chris Page.

"As well as women who came from urban and rural areas, and all different income backgrounds.

The diverse movement was built on the women's movement and the trade-union movement.

"We felt we had a good group of people who experienced the Troubles and had something to say about what coming out the other side might look like," she said.

"We were very much accidental political activists."

The misogyny they faced has been well documented.

They were heckled, told to sit down and mooing sounds were made at them.

Bronagh Hinds said women involved in the talks process experienced misogyny

Bronagh Hinds said one incident, where then DUP leader Ian Paisley tried to brush her aside, has been replayed on TV over the decades.

"I think he was rather miffed because the Women's Coalition had got out to the press first as we often tried to do to spread the good news before someone came along and stirred it up with the bad news," she told the BBC's Red Lines podcast.

She said misogyny happened primarily at the political forum that accompanied the talks.

However she said that for the most part the public did not like what they saw and things began to "calm down".

Former Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) leader Dawn Purvis said she remembered David Ervine - then PUP leader - going to speak to talks chairman Senator George Mitchell about "some of the rudeness".

Liz O'Donnell was an Irish junior minister for foreign affairs at the 1998 talks.

"What had passed for politics unfortunately in Northern Ireland had been name calling and there was plenty of misogyny around as well," she told BBC News NI.

However she said Senator Mitchell would not tolerate bad behaviour and he brought his own "civility and dignified ways to the proceedings".

The secretary of state

Mo Mowlam was the secretary of state for Northern Ireland during the 1998 talks process

The late Mo Mowlam, who took on the role of Northern Ireland secretary of state at a crucial time in the peace process, had an unconventional approach.

She visited the paramilitary prisoners at the Maze high-security jail in an effort to get them to support peace talks.

"If you want progress, you ain't going to get it if you don't have talks," she said at the time, external.

Talking about the days leading up to the agreement, Monica McWilliams said Dr Mowlam put her "heart and soul into making those last nights work".

That was at a time when she had a drip in her arm and was being treated for cancer.

Prof Yvonne Galligan said the secretary of state had "incredible courage, confidence in herself and belief in a positive outcome and in the trajectory towards a peace process".

Her step-daughter Henrietta Norton said Mowlam would want her legacy to be defined by "giving opportunities to young people and making the future a better place".

'Women have been overlooked'

"Northern Ireland is an old-fashioned society and they do seem to concentrate more on what men do," said Eileen Bell.

"To some extent we don't make our voice heard.

"I think the role of a lot of women within the negotiations has not been recognised to the degree it should be.

"For example Mo Mowlam, Martha Pope (Senator Mitchell's chief of staff) and other women like Bríd Rodgers, Bairbre De Brun, women from the Women's Coalition and and women in smaller parties - all played important roles and highlighted the institutional misogyny that existed," said Dawn Purvis.

She said that while women are more "visible" in politics "we have a massive way to go before women have equal representation".

For Bríd Rodgers, who would go on to be an executive minister, the role of women was underplayed, which she said was "nothing new in Irish history".

Bríd Rodgers pointed to women who were not directly involved in politics, including the late Pat Hume - the wife of then SDLP leader John Hume

Monica McWilliams said there was "still is a democratic deficit, in terms of women in public decision-making," but added: "Twenty-five years later now people recognise it - they're calling it out.

"They also do not tolerate the misogyny that I had to put up with, which was quite shocking.

"When you transform a society from conflict, that's part of it. You need to change those attitudes as well."

Nine influential women have been painted by artist Marian Noone, aka Friz

Prof Galligan feels that recognising women's role in the peace process is important as an example to other countries.

"There are many other peace processes around the world that look to Northern Ireland as a blueprint for success," she said.

"So I think we have an obligation to recognise fully the role that women played in the peace process, not just for our own sakes but for the sake of other global conflicts around the world."

Women, politics and social media

While society has changed since the 1990s, Prof Galligan said misogyny towards female politicians had moved onto social media.

She believes it is one of the biggest things that puts women off going into politics.

A number of women, including former first minister Arlene Foster and former deputy first minister Michelle O'Neill have spoken out about the abuse they have faced.

Prof Galligan said five Cs of why women were not going into politics had been identified: cash, culture, childcare, confidence and candidate selection.

"Now we need to add an S - overriding those now is social media," she said.

Arlene Foster and Michelle O'Neill have both been targeted by online trolls

Prof Galligan believes ending online anonymity and ensuring women are supported by their parties can tackle that.

"The discourse is unregulated and there is no way of no effective way of sanctioning these kinds of misogynistic remarks that are directed towards women politicians," she said.

"It's it really is a problem of our times and one that we really need to get a handle on."

One important way to get women into politics is a "role model" effect, Prof Galligan believes.

"It's very important to see women in politics because you cannot be what you cannot see," she said.

She added that if women, who make up half the population, were not around the table then decisions would "not be based on a democratic reflection of the views of the population".

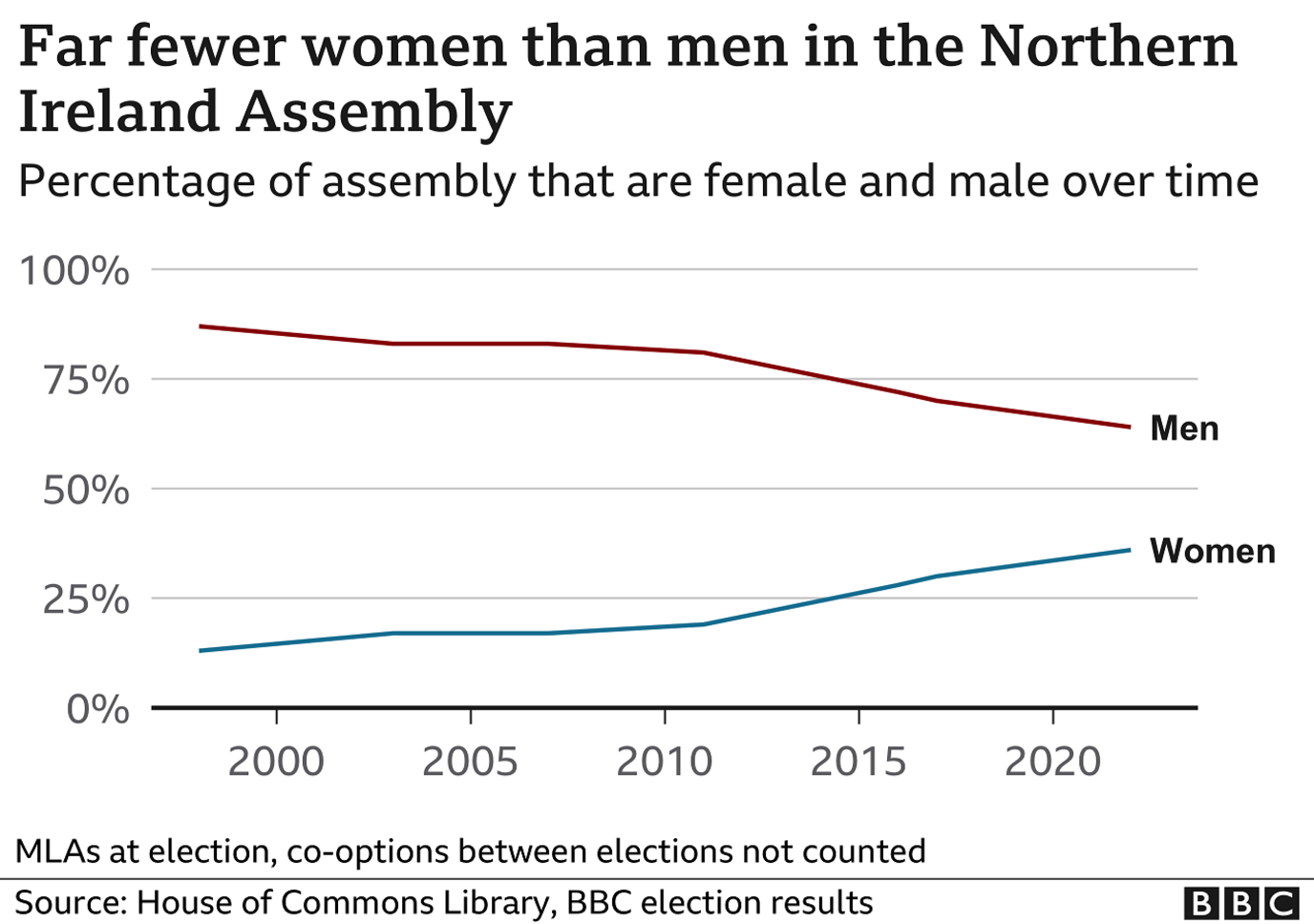

In the last Stormont elections in May 2022, 87 women ran as candidates - the highest number in history.

Thirty two of the 90 MLAs elected were women.

- Published2 July 2022

- Published10 May 2021

- Published3 April 2023

- Published13 January 2023