Good Friday Agreement: Does the peace deal still work?

- Published

Signs like this one in County Antrim have appeared in the wake of the post-Brexit arrangements for Northern Ireland

It is fast becoming the new Stormont protocol - when there is a big milestone to be marked, Northern Ireland's power-sharing government and its institutions are nowhere to be seen.

When the Good Friday Agreement was passed in a referendum in 1998 it didn't just bring the 30 years of conflict known as the Troubles to an end.

It also established the devolved government that was to guide Northern Ireland into its era of peace.

But on the 20th anniversary of the deal in 2018 the political institutions were in cold storage.

Sinn Féin had triggered their collapse in protest over the Democratic Unionist Party's (DUP's) role in a controversial renewable energy scheme.

And Stormont is mothballed again for the 25th celebrations this week after the DUP pulled it down, this time over its opposition to the Northern Ireland Protocol, the rules set up to oversee post-Brexit trade.

We shouldn't be surprised - it's a well-worn political path.

Vetoes and 'ugly scaffolding'

The power vacuum is more keenly felt this year with a president and a prime minister arriving for the party.

No wonder the White House opted to steer clear of the tumbleweed blowing through Stormont.

Instead it choose instead to use a shiny new £350m university campus as the Biden backdrop - perfect surroundings for the presidential speech writers to focus on the future and not the political turbulence of the past 25 years.

But some uncomfortable facts are hard to airbrush.

For nine of the 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement was signed Stormont has been shut down.

It is essentially a political brake just waiting to be pressed.

But that is what it had to be to win over reluctant power-sharers back in 1998.

The so-called "ugly scaffolding", which keeps the Stormont institutions propped up, is laced with vetoes to safeguard the interests of all sides.

Under power-sharing, nationalist and unionist political parties form a governing executive alongside a legislative chamber made up of assembly members.

However within that framework there is the designation system.

That requires assembly members to declare as nationalist, unionist or other for the purposes of cross-community voting.

If a large group of assembly members - at least 30 - do not like a decision they can use the controversial petition of concern.

That blocks that decision unless it receives cross-community approval from a majority of both nationalist and unionist members.

Meanwhile the top two jobs - first minister and deputy first minister - are bound together, meaning one cannot remain in office without the other.

If one quits - like Martin McGuinness did in 2017 and Paul Givan in 2022 - then they both go.

Progress or polarisation?

But far from shoring up the gains of the Good Friday Agreement the Stormont safeguards have held back political progress.

They have led to stop-start government and hindered long-term efforts to deal with deep-seated problems in health and education.

The Good Friday Agreement: A brief guide

Beyond Stormont many believe the vetoes have only served to cement further polarisation in Northern Ireland.

Repeated surveys show public confidence in Northern Ireland's political institutions remains consistently low.

That is why every Good Friday Agreement anniversary now comes with a debate about whether the accord is past its best-before date.

Changes were made to the Good Friday Agreement during political negotiations at St Andrews in 2007, external, clearing the way for the DUP and Sinn Féin to share power.

But others are now calling for more changes to be made.

The two men who were first to sign the agreement believe there is room for extra "tweaks" but they warn against more fundamental changes

Read more about the agreement

EXPLAINER: What is the Good Friday Agreement?

BACKGROUND: How did the agreement come about?, external

ANALYSIS: The political road to Good Friday

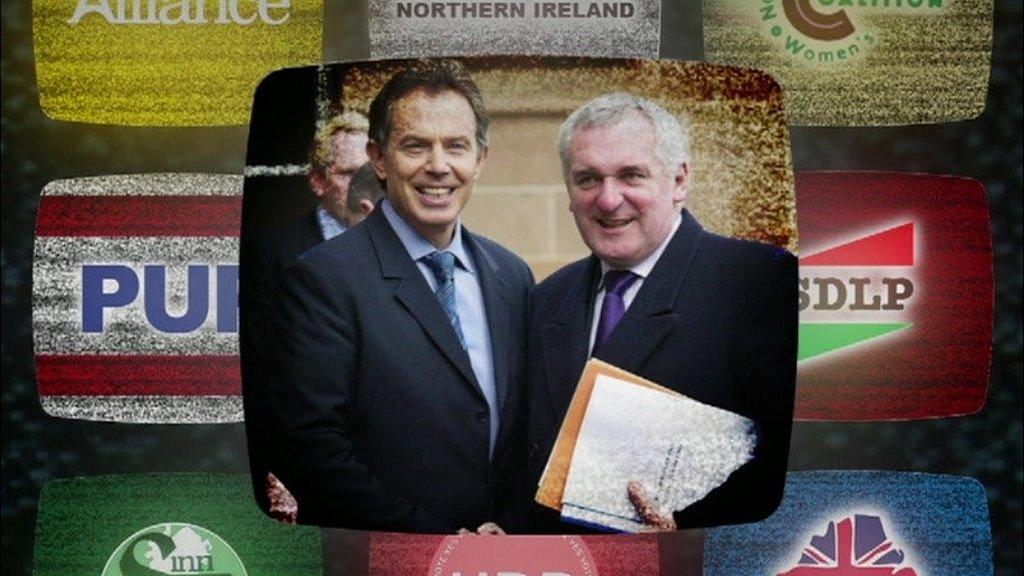

Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair were two of the key architects of the Good Friday Agreement

Former Prime Minister Tony Blair says politics always "evolves and changes".

But he warns that "the important thing is that we keep what is the essential principle of the Good Friday Agreement, which is that the constitutional status of Northern Ireland is decided by the people there".

His co-signatory, former Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern, says there is no appetite to fundamentally rewrite the agreement.

"To get any other type of agreement it has to be agreed by everybody," he says.

"It is no good somebody having a pipe dream on how they can do it better."

He adds that getting everyone to have the same goal "will be very difficult to do".

Another key negotiator at the time, Lord Empey, believes the agreement has already been weakened by the St Andrews deal.

The former Ulster Unionist Party leader says the decision to remove the power of assembly members to elect the first and deputy first ministers on a cross-community platform has backfired on the DUP.

In the assembly election last year Sinn Féin became the biggest party and so is eligible to nominate its vice-president Michelle O'Neill as Northern Ireland's first-ever nationalist first minister.

However before the St Andrew's Agreement both posts were jointly elected by the assembly with cross-community support from both unionists and nationalists.

"Had they left it alone what we had negotiated (DUP leader) Sir Jeffrey Donaldson would have been eligible to be first minister, not Sinn Féin's Michelle O'Neill," he says.

He added: "But because of the changes at St Andrews she is now eligible to be first minister.

"It has come back to haunt the DUP."

More change on the horizon?

But the assembly's first speaker Lord Alderdice says further changes to the Good Friday Agreement are inevitable.

The former Alliance leader believes the surge in support for his old party reinforces the need to ditch Stormont's designation system.

Alliance Party assembly members are overlooked in cross-community votes as they designate as others and not either unionist or nationalist.

"This system helped to polarise Stormont and put people in boxes," he says.

He supports a move towards using weighted majorities instead of cross-community voting.

For example the backing of 60% of assembly members would be enough to approve decisions.

But revisiting the Good Friday Agreement for a second time will carry great risks, according to a former civil servant who was involved in the 1998 talks.

Mary Madden says that once you "unravel" one part of the agreement other parts could quickly unravel too.

She doesn't believe the UK and Irish governments are up for renegotiating such a hard-fought deal.

Chances are that by the time the 30th anniversary comes around the Good Friday Agreement will still be intact.

And in keeping with tradition the Stormont institutions it created could well be back in the deep freeze once more.

Stormont's stand-offs and suspensions:

2 December 1999 - Stormont's first generation of ministers take up their posts as the new executive meets for the first time, external.

11 February 2000 - After just nine weeks, the executive is suspended by Secretary of State Peter Mandelson, external because of the lack of progress on IRA decommissioning.

30 May 2000 - Devolution is restored after three and a half months (109 calendar days), external as the IRA pledges to put its weapons beyond use.

1 July 2001 - First Minister David Trimble resigns over IRA decommissioning, external but nominates UUP colleague Sir Reg Empey as acting first minister, triggering a six-week deadline to fix the impasse.

11 August 2001-Secretary of State John Reid suspends the devolved institutions for 24 hours, external, giving the parties a further six-week window to resolve the decommissioning dispute.

22 September 2001- A second 24-hour suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly comes into force, external as John Reid warns parties it is the last chance to break the decommissioning deadlock.

15 October 2002 - John Reid suspends devolution again, external after police raid Sinn Fein's Stormont offices as part of an investigation into allegations republicans were spying on the government.

8 May 2007 - Devolution is restored after a gap of almost five years (1,666 calendar days), external, during which Northern Ireland was governed via direct rule from London.

10 September 2015 - The DUP's Peter Robinson steps aside as first minister and pulls all but one of his ministers out of the executive amid accusations of IRA involvement in a 2015 murder.

September - October 2015 - The executive continues working through the crisis so reappointed DUP ministers begin a policy of rolling resignations, staying in office for only a few hours each week to prevent other parties from taking over their departments.

9 January 2017 - Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness resigns as deputy first minister in protest over the DUP's role in a controversial renewable energy scheme, causing the executive to lose its powers.

11 January 2020 - Devolution is restored again after three years of paralysis (1,097 days) as the parties sign up to the New Decade, New Approach agreement, designed to stabilise power sharing.

14 June 2021 - Arlene Foster resigns as first minister due to an internal DUP revolt but Sinn Féin refuse to go back into government with her replacement unless there is progress on Irish language legislation. A deal is done and the DUP's Paul Givan becomes first minister three days later.

4 February 2022 - Paul Givan resigns as first minister in protest over the Irish Sea border, triggering the automatic resignation of the deputy first minister.

Declan Harvey and Tara Mills explore the text of the Good Friday Agreement - the deal which heralded the end of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

They look at what the agreement actually said and hear from some of the people who helped get the deal across the line.

Listen to all episodes of Year '98: The Making of the Good Friday Agreement on BBC Sounds.

- Published3 April 2023

- Published16 February 2023

- Published4 April 2023