Good Friday Agreement: The view from the Republic 25 years on

- Published

Watching the St Patrick's Day parade in Dublin on 17 March 1998. Two months later voters in the Republic voted by a huge majority to renounce its constitutional claims to Northern Ireland

As part of the Good Friday Agreement, the Republic of Ireland voted by more than 90% to change its constitution.

In the 1998 deal, the Irish government agreed to renounce its constitutional claims to Northern Ireland.

The territorial claim in Articles Two and Three had long offended unionists.

They were amended to incorporate the principle of consent - there could be no change to the constitutional position of Northern Ireland without the consent of the majority.

Diarmaid Ferriter, professor of modern Irish history at University College Dublin, believes that change was very significant.

"It was really about emphasising that while the constitutional aspiration would still be Irish unity," he says.

"It could only be achieved through peaceful means and consent and through a vote in favour on both sides of the border of Ireland.

"That was a very important historical shift away from the idea that republicans had that a single all-island vote in favour would suffice."

As new leaders with new challenges - mainly economic - took over in both the Republic of Ireland and the UK, less political time was devoted to Northern Ireland.

Queen Elizabeth II arrives for a state banquet in Dublin Castle with the then Irish president Mary McAleese in May 2011 in Dublin

Nevertheless it provided the backdrop to the Queen's historic state visit in 2011.

"With the benefit of historical hindsight we can all see things which we would wish had been done differently or not at all," she told the state dinner at Dublin Castle.

"But it is also true that no-one who looked to the future over the past centuries could have imagined the strength of the bonds that are now in place between the governments and the people of the two nations."

Likewise, nobody could have foreseen what would happen five years later when the UK voted to leave the EU.

Mark Simpson looks at the details of the Good Friday Agreement

The peace process and the Good Friday Agreement had come about at a time when the EU's single-market borders became largely invisible.

"The peace process in itself was definitely one of the catalysts for an all-island economy developing organically," says Danny McCoy, chief executive of Ibec, the Republic of Ireland's equivalent of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI).

"We see a lot of businesses have now created their business model on servicing the island of Ireland as a whole.

"We also see significantly in the labour market interactions between people going north and south - not just on their daily business but also to work and to live in one jurisdiction and work in the other."

Boris Johnson and Leo Varadkar meet at Thornton Manor near Liverpool in 2019 for talks on post-Brexit arrangements that were to lead to the Northern Ireland Protocol

Then in 2016 came Brexit, challenging the cosy presumptions from the period following the Queen's visit, with borders once again on the political agenda and British-Irish relations suffering.

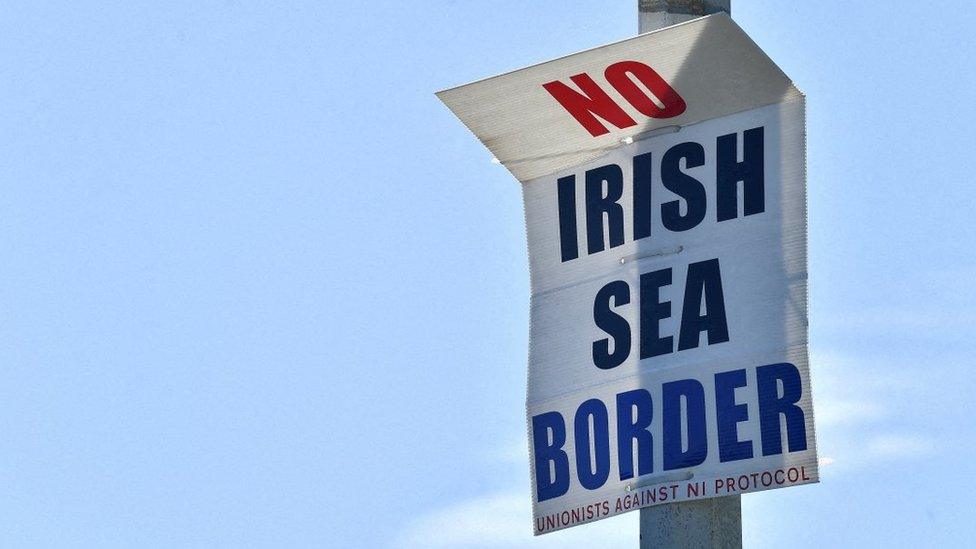

In 2021 the Northern Ireland Protocol, agreed by then Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the EU, came into force.

Under it, to avoid physical checks on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, inspections of goods entering Northern Ireland were introduced at its ports.

Unionists said the protocol effectively created a trade border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK, and in 2022 the DUP walked out of power-sharing at Stormont over it.

As a result Northern Ireland is still without a functioning assembly or governing executive.

Former diplomat Rory Montgomery was part of the Irish team that negotiated the Good Friday Agreement and was centrally involved in Dublin's approach to Brexit.

"Then Boris Johnson arrived - about whom the less said the better maybe," he says.

"I think relations reached a nadir under him. Truss was not there long enough to make a difference.

"I suppose there's at least a sense now that Rishi Sunak is a serious, principled person who is trying his best to resolve the very real problems which exist."

Now 25 years on from the Good Friday Agreement, many insiders in the Republic, seeing the lack of a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, privately regret that the potential of the deal has not been realised, particularly on north-south bodies.

And 25 years from now few - once again privately - believe Northern Ireland will exist, at least in its current form.

Related topics

- Published20 May 2011

- Published2 February 2024

- Published3 April 2023