Jellyfish: Should sea swimmers expect to see more?

- Published

Regular sea swimmers know that when the sea is getting warmer, it means a return of jellyfish like the Lion's Mane

Global sea surface temperatures for April and May were the highest on record for those calendar months in a series stretching back to 1850, according to the Met Office.

When you look at regional examples, the picture becomes even more stark.

The temperature rise in the North Atlantic in May was record-breaking.

Some of the most intense marine heat increases on Earth have developed in seas around the UK and Ireland, the European Space Agency (Esa) says.

Water temperatures are as much as 3C to 4C above the average for this time of year in some areas, according to analysis by Esa and the Met Office.

The sea is particularly warm off the UK's east coast from Durham to Aberdeen, and off north-west Ireland.

If you're a sea swimmer you might think this is great news.

I ventured back into the North Atlantic at Portstewart in June for the first time this year.

To me, it was still very cold but one of the regular swimmers commented on how warm it was.

I thought, 'Tell my butt cheeks that'.

Jellyfish season

Sea temperatures lag behind air temperatures.

The maximum air temperature in Northern Ireland usually occurs in July whereas sea temperatures are at their warmest in August and September.

Regular sea swimmers will also know that when the sea is getting warmer, it means a return of the jellyfish.

The jellyfish season is normally April to October and jellyfish are currently swimming around the Irish coastline and a few have been spotted on our local beaches.

Luckily Irish waters are not home to the most dangerous jellyfish known - the Box jellyfish - which is common in Australia. Jellyfish stings in Ireland are not usually life threatening but can be very painful.

Jellyfish possess stinging cells, known as stingers, on their tentacles.

Brushing against tentacles can cause the release of these stingers which contain venom.

Depending on the type of jellyfish, the stingers may not be sharp enough and long enough to pierce the skin and the skin forms a natural barrier to most stings.

More delicate areas, such as the eyes and lips, might be more easily pierced.

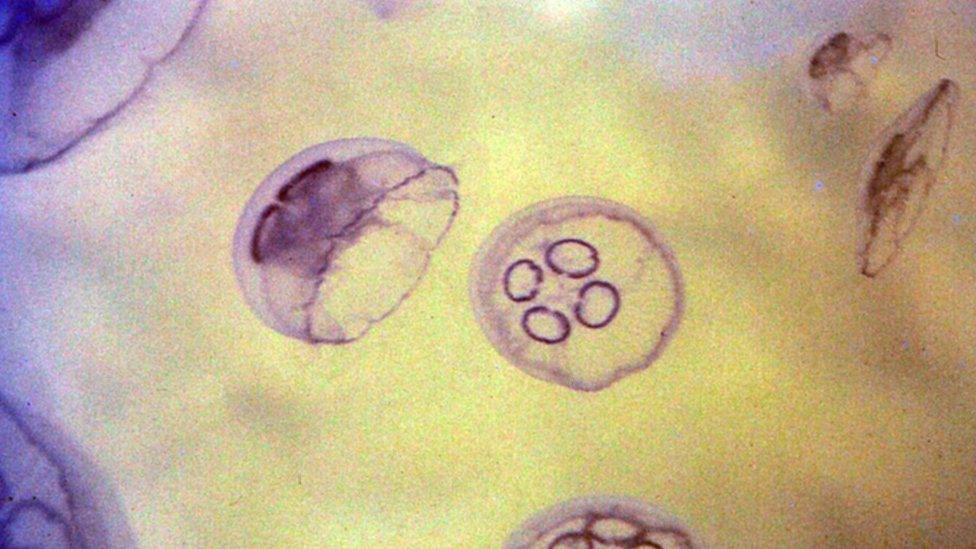

Moon jellyfish or Aurelia aurita are relatively harmless to humans

There are six or seven species of jellyfish that are often found in Irish waters, the most common is the Moon jellyfish which is about the size of a dinner plate.

It is very transparent and has a tendency to swarm, but the good news is that they are relatively harmless to humans, although they have been known to block boats engines.

Swimmers though should beware the Lion's Mane, which is a brownish colour and its relative, the Blue jellyfish.

Dr Brown, who has more than 50 years experience in his field, also spotted moon jellies in Sweden

Both are prevalent in the warmer summer months and the Lion's Mane has already been spotted off the north coast.

They have long tentacles which can give a nasty sting, albeit not lethal.

The tentacles can break off and become attached to chains on a boat for example but the cells that sting will stay alive for quite some time even when not attached to the main body.

Regular sea swimmers and holidaymakers should avoid jellyfish if at all possible. Do not touch them out of curiosity.

Social media has lots of sea swimming groups that will post information on jellyfish sightings.

If you do spot a jellyfish floating in the water, don't try and move it or wave it away, simply move out of its path and alert others to its presence.

Another dangerous species that is more common in Mediterranean waters but has been known to swim north, when the weather here is warm and settled, is the Mauve Stinger.

It too has a tendency to swarm and can kill other marine life including fish.

In 2007, a whole school of fish was killed by a swarm of Mauve Stingers at a salmon farm in Glenarm, County Antrim. , external

Warming seas can mean the jellyfish season is longer as the ideal temperature will be reached earlier and stay well into the autumn and the likes of the Mauve Stinger will become more commonplace.

The distribution of plankton as a whole will shift northwards as the ideal temperature zones moves north.

According to Dr Brown, a marine biologist on the Ulster Wildlife council, there are signs that this is already happening as seabirds and small fish are migrating north.

But there is also the possibility of new species of small fish and birds that originate in Mediterranean areas coming north too.

There are some other factors to consider as rising sea temperatures could lead to a shift in the natural sea fronts which, just like weather fronts mark boundaries between air masses, mark a change in temperature between one body of water and another.

If these natural barriers move this could also impact marine life.

Related topics

- Published19 June 2023

- Published18 August 2020

- Published30 July 2016