Covid Inquiry: Victim's family told virus would be 'gone by summer'

- Published

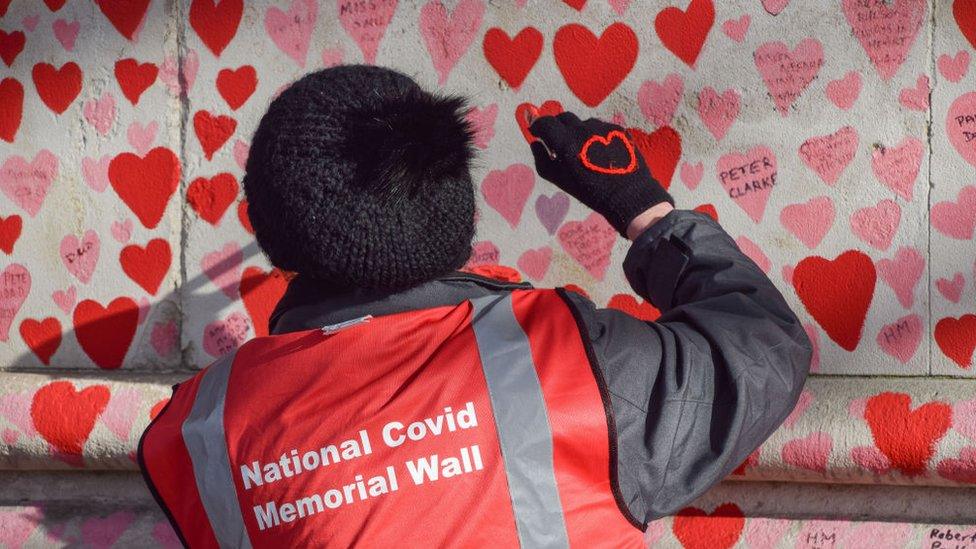

Brenda Doherty: 'My mummy was not cannon fodder'

The daughter of the first woman to die in Northern Ireland with Covid-19 has said her family was initially told the virus would be a "flash in the pan and gone by summer".

Brenda Doherty's mother Ruth Burke, 82, was infected after being admitted to hospital in March 2020.

Ms Doherty told the Covid Inquiry about the last time she saw her mother.

She took her mother's face in her hands, kissed her and told her she would see her the next day.

She did not see her again.

Her mother had been fit to be medically discharged but a delay in accessing a care package meant she had to stay in hospital an extra night. During that time, she tested positive for coronavirus.

A representative of each of the UK nations' Covid bereaved family groups has been appearing before the public inquiry.

Ms Doherty, who is a leading figure in the Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice group, has previously called for Northern Ireland not to become a "footnote" in the inquiry.

She said that after then Prime Minister Boris Johnson had given his lockdown speech in March 2020 she received a call from the hospital asking if she agreed to her mother not receiving medical intervention.

The doctor told her that her mum had suffered liver and kidney failure and her heart rate was under tremendous pressure.

She asked if it was a "battle" her mum "was not going to win", to which the doctor answered: "Yes."

Kindness of a nurse

Tuesday is the final day of evidence for the inquiry's first module, which is looking at resilience and preparedness.

Ms Doherty told the inquiry her family did not get her mother's clothes back. Instead they were incinerated.

However, they did get their mother's cross and chain, thanks to the kindness of a nurse.

Brenda Doherty's mother Ruth (left) was the fourth person in Northern Ireland to die after having contracted coronavirus

Recalling her mother's funeral, she described it as a "committal", where only she and her sister could stand at the graveside, while eight other family members stood behind red tape a distance from the grave.

"I played Amazing Grace on my phone and then I watched the cemetery attendant put the watch up telling me the time was up and then my family and I went our separate ways," she said.

She told the inquiry that it became apparent there were failings across the system, and that when it came to dealing with people who died from Covid "health trusts were all doing different things".

Ms Doherty said she wanted to find out what had gone wrong in order to ensure "no other family has to go through that again".

"We need legislative change in Northern Ireland," she said.

"There is so much that happens - for instance DNRs (do-not-resuscitate orders) on their loved ones without consultation; the visitation rights that were not allowed despite the care partners' guidance which was in place."

Favourite red dress

In March 2020, Ms Doherty spoke to BBC News NI just hours after she received a call from the hospital telling her that her mother had died.

She described the family's pain of not being able to sit with her during her final hours.

Ms Doherty said the family had so many regrets, including not being able to kiss their mum one last time or being able to bury her in a favourite red dress.

What is the inquiry about?

The Covid Inquiry is taking evidence about the UK's handling of the pandemic by politicians, officials and experts.

It was first announced by then Boris Johnson in 2021 and covers decision-making during the pandemic by the UK government and in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Some of the more controversial issues under examination include delayed lockdowns, the move to abandon testing in the community in March 2020, the approach to care homes and whether too many restrictions were imposed as the pandemic progressed.

It is split into different modules with future strands yet to be announced - the inquiry plans to hold hearings until at least 2025.

Members of the public are invited to share their experiences through the inquiry's Every Story Matters project.

The Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice campaign group - which has criticised the government's handling of the pandemic - urged the inquiry to ensure these voices are heard.

Read more: How will the Covid Inquiry work?

What's been said so far?

Public hearings for Module one - resilience and preparedness - began on 13 June and the inquiry has already heard from political figures such as former Prime Minister David Cameron, former Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and the former Health Secretary Matt Hancock.

The agenda over the past two weeks has been mostly dominated by Northern Ireland, with several key figures presenting their evidence to the inquiry.

On 6 July former Health Minister Robin Swann told the inquiry that a lack of reform and investment in the health service hindered its response to the pandemic.

His evidence was followed by Northern Ireland's chief medical officer Sir Michael McBride, who said the absence of Stormont ministers in the three years before the pandemic had a "significant impact" on preparedness.

Baroness Foster and Michelle O'Neill appeared before the inquiry last week

Former First Minister Baroness Foster and former Deputy First Ministers Michelle O'Neill presented their evidence last week.

Baroness Foster told the inquiry that the UK government should have stepped in to make decisions in the absence of ministers at Stormont.

Ms O'Neill said there were "ad-hoc and tick-box" meetings between Stormont ministers and the UK government during the pandemic and there was not an "easy flow of information" between the two.

On Monday, the panel heard that people from less well-off backgrounds in Northern Ireland were more likely to be hospitalised during the pandemic.

- Published17 July 2023

- Published25 April 2023