Booker Prize: What are the secrets to Ireland's success?

- Published

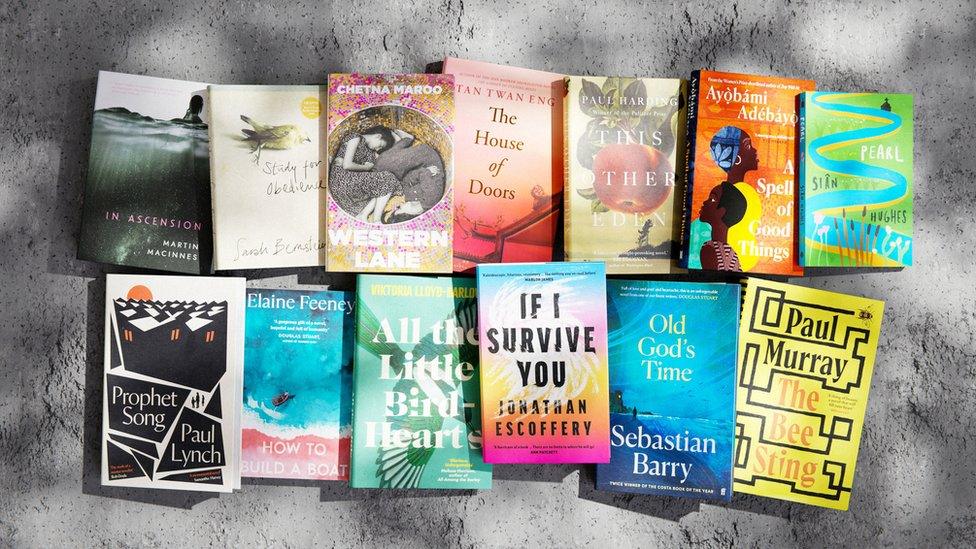

Four books by Irish writers are on this year's Booker Prize longlist

Since the Booker Prize first claimed to name the best novel of the year written in English, Irish writers have won the accolade five times in 54 years.

Possibly more impressive, however, is the consistency with which Irish authors have appeared on the longlist for the world's most famous prize for writing.

At least one Irish author has appeared in 16 of the past 20 years, with many years featuring multiple Irish writers.

This year, there is no shortage of Irish contenders.

Four Irish authors make the 13-strong longlist, the most ever in a single year.

They are Paul Murray with The Bee Sting, Paul Lynch and his novel Prophet Song, Elaine Feeney for How to Build a Boat, and Sebastian Barry with Old God's Time.

So with Ireland making up only about one percent of the native English speaking population of the world, what makes the island so good at punching above its weight in writing novels?

'Ireland believes in its writers'

Gaby Wood, chief executive of the Booker Prize Foundation, says the proportion of Irish writers is remarkable in relation to the country's size.

"Literature is both familiar and respected in Ireland - it feels like something you can take part in, and something on which the present is built," she says.

Gaby Wood says literature is familiar and respected in Ireland

"As literary exports go, Ireland hasn't had bad ones. As a result - and this is the second factor - the practice is supported by the government.

"Ireland believes in its writers and understands the economic challenges they face - a room of one's own is not easy to come by."

Ms Wood also notes the breadth of writing coming out of Ireland at present.

"I would actually point to the differences between these books - Prophet Song couldn't be less like The Bee Sting."

Having been a judge herself, and now sitting in on all meetings of judging panels, Ms Wood says it is a huge task complicated by the "impossibility of comparing one novel to another".

"They may be the same art form but they can feel like different species."

But she acknowledges that it's not possible, nor even desirable, to choose a definitive best book of the year.

"The announcement of the winner is an invitation to conversation," she said.

'Writing begets writing'

Chris Morash, a professor of Irish writing at Trinity College Dublin, says there is no "simple answer" that explains Irish writers' fine track record.

But one possibility, he argues, is that success begets success and "writing begets writing".

Irish writers' support for one another is one factor that pushes them to success, says Juliet Mabey

"If you're a young writer and you're thinking about a career as a novelist, you look around and there are two or three generations there before you.

"It kind of gives you an example of what it is to be writer."

He says that Ireland's history of producing great literature is also a lens through which readers can understand new books from the country.

"Ireland has the literary reputation going back to Joyce, Beckett, Yeats.

"So when a reader goes into a bookstore in Los Angeles or New York or Sydney they see an Irish name and they associate that with a literary culture in a way that you might not with a lot of other countries."

'The Sally Rooney effect'

An important step on a writer's path to accolades is getting the attention of a publisher, something else that Prof Morash believes has been made easier for up-and-coming Irish writers by the country's literary pedigree.

Sally Rooney's second novel Normal People was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2018

"If you're an agent or a publisher... you're looking for the next Sally Rooney, you're looking for the next Anne Enright, you're looking for the next John Banville.

"We particularly saw it with the success of Sally Rooney and of [her massive best-seller] Normal People - there have been a series of writers that have been published since where you can kind of see the Sally Rooney effect."

'The Irish scene is collegiate'

Juliet Mabey is the founding publisher at London-based Oneworld Publications - she edited and published Paul Lynch's Prophet Song, one of the four Irish works on this year's booker longlist.

She says the Irish literary scene is something she keeps an eye on for new talent.

"The Irish writing scene is very collegiate, they support each other a lot, they help mentor each other - that in itself is something that publishers are probably aware of," she explains.

"If you look at the number of endorsements [from fellow Irish authors] that Paul's book had on publication, he had like seven or eight on the cover.

"They all had something really important to say about the book."

Ireland is a popular setting among readers, according to Ms Mabey - so much so that when Lynch was writing his novel Beyond the Sea, set of the west coast of South America, she tried to convince him to instead set it in his native Ireland.

As a publisher she has a responsibility for submitting works for many of the big literary prizes.

There's an art in matching up "the type of writing and the type of story", she says, with the Booker judges always looking for something that is "really original, that stands out - books that have something to say for themselves".

The most recent Booker Prize winner from Ireland was Anna Burns in 2018 for her novel Milkman

'The moral compass in Irish writing'

Liam Harte, a professor of Irish literature at the University of Manchester, agrees that Ireland has done a particularly good job of "fostering and promoting its writers" in recent decades.

He points to what he describes as the "importance of reading in Irish culture" and the ways that is manifested through public policy.

"Libraries still being funded, being protected from some of the worst of the austerity cuts… the arts councils north and south are well funded… the arts exemption tax scheme," he cites.

"The Republic in 2015 established a laureate for Irish fiction… that also says something about the profile it gives writers in the culture.

"Irish readers in particular take an interest in literature and what writers are saying, perhaps more than in other countries.

"[Irish writers] deal with a kind of moral compass that readers look to for guidance through the chaos, and Irish history is nothing if not in a state of constant flux."

'They speak to universal concerns'

Prof Harte says that while the books of many of the Irish writers recognised by the Booker Prize are works grounded in Ireland, they speak to a wider audience.

The most recent Irish winner was Anna Burns for her novel Milkman, which, while it is never expressly stated, is set in Troubles-era Belfast.

"[It] is extremely specific, not even to the whole Island, but to one part of it - we're talking about streets and avenues" says Prof Harte.

"And yet I think that has global resonance that speaks to other cultures where the past is still a suffocating presence... it's also about trauma, it speaks to universal concerns."

A shortlist of six books for the Booker Prize will be announced on 21 September, with the winner to be revealed on 26 November at a ceremony in London.

The shortlisted authors each receive £2,500 and a specially bound edition of their book, while the winner will get a further £50,000 and a Booker Prize trophy.

- Published17 October 2022

- Published17 October 2018