What does future hold for Lough Neagh, UK's largest freshwater lake?

- Published

Blue-green algae is toxic to animals and can cause illness in humans (file image)

After a summer of blue-green algae, bathing bans, and pondweed and silt causing problems for boats, Belfast City Council recently added its voice to calls for Lough Neagh to be brought into public ownership.

But who owns it now and who is responsible for its operation and management?

The simple answer is... it's complicated.

Why Lough Neagh matters

The largest freshwater lake in the UK supplies half of Belfast's drinking water and 40% of Northern Ireland's overall.

It is also home to the largest commercial wild eel fishery in Europe.

And sand-dredging, though controversial, has been a business on the lough for over a century.

The lough and its catchment area is also a vast ecosystem, where species such as the curlew and the barn owl could be found in years gone by.

It has numerous environmental designations - special protection areas, special areas of conservation, areas of special scientific interest and Ramsar status.

Lough Neagh is home to significant native species such as eel, trout and pollan

And the peatlands that surround it are a potentially huge carbon sink, helping to fight climate change.

What's gone wrong?

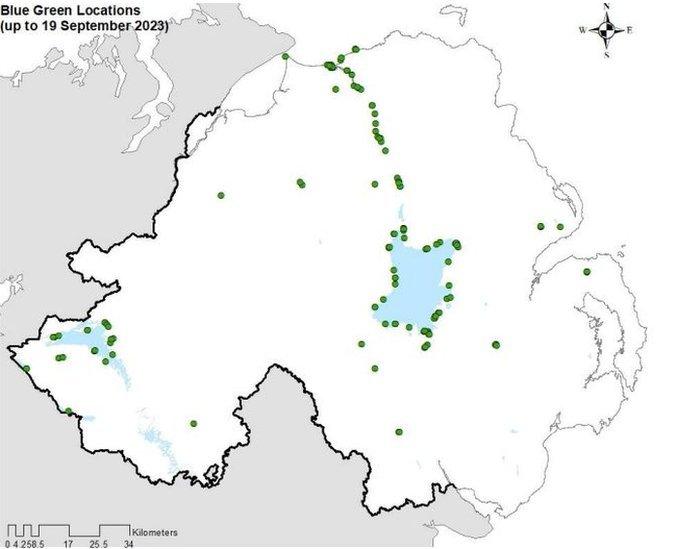

The blue-green algal bloom over the summer has caused havoc, not just in Lough Neagh but right up to Northern Ireland's north coast.

Water from Lough Neagh flows down the Upper Bann and into the Atlantic Ocean at the Barmouth between Portstewart and Castlerock in County Londonderry.

That brought the algae to the coast, where it could not survive but caused a bathing ban on several beaches at the height of summer.

There were also bathing bans in areas around the lough.

Some traders blamed the effect of those bans for putting them out of business.

Anglers have been advised to catch and release fish that have been within Lough Neagh because of the risk the algae poses.

The bloom was the result of settled weather, invasive species and water pollution mostly due to agriculture.

The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (Daera) has released images and maps showing the extent of the problems facing the lake.

A recent map showed the different parts of Northern Ireland where the algae has been found

Excess fertiliser runs off from fields into the water, taking growth-stimulating nitrogen and phosphorus into the lough.

Almost two decades ago the zebra mussel invaded the lough.

It filters water, making it clearer and allowing the sun's light to penetrate deeper into the depths.

That, combined with the excess nutrients from fertiliser - eutrophication - caused the algae to "bloom" or grow rapidly.

The algae compounded the woes of rescue volunteers who were already worried about safe access due to silt building up.

Pondweed is also a prominent invasive species in the lough.

And the lough is showing signs of the effects of climate change, with water temperature now more than a degree higher than in 1995.

So who is responsible?

Let's start with who owns what.

The Shaftesbury estate owns the lough bed and the soil, the banks, the rights to sand extraction and shooting licences for wildfowl.

That ownership dates back to the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th Century.

Ownership of and responsibility for Lough Neagh does not sit with any single department or group

The National Trust, various councils, different charities and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs all own areas around the lough, including national nature reserves.

But no single body owns the lough, its water or the water that flows in and out of it.

Because no one individual or body or government department is responsible, many organisations and community groups have formed to try to protect and restore the lough.

The Lough Neagh Partnership was established 20 years ago to help manage and protect the lough.

Swimmers at Ballyronan on the edge of Lough Neagh were warned against entering the water in June

It is comprised of elected representatives, landowners, fishermen, farmers and communities.

"Save Our Shores! Protect Lough Neagh and our inland waterways" is a group on Facebook with more than 2,500 members, including swimmers, conservationists and environmentalists.

And the Love Our Lough group held a wake for the lough on 17 September calling for cohesive management and protection of it.

Action is also being taken by scientists.

They are advising farmers through the Soil Nutrient Health Scheme, which aims to enable those in the agriculture industry to apply fertiliser strategically, reducing run-off and the resulting pollution.

Northern Ireland Water, the government-owned body that provides water and sewerage services, is replacing its treatment facility at Ballyronan in County Londonderry to improve how it deals with waste-water and enhance water quality in the lough.

Can it not just be taken over by someone?

That would be very complicated given that so many bodies have interests in the lough.

But that has not stopped different administrations considering it over the years.

Now a motion by Green Party councillor Brian Smyth, passed by Belfast City Council, is the latest in a long line of discussions about getting the lough into public ownership.

Five rivers flow into Lough Neagh, the largest freshwater lake in the UK

It is a prospect also on the mind of Gerry Darby, the manager of the Lough Neagh Partnership.

He said the partnership had recently received a significant grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, which would allow it to carry out an economic appraisal to address the future ownership and the management of Lough Neagh.

The group signed a letter of offer and expects the process to take about two years.

"It will also allow us to submit a business proposal, which would look at how much this would cost and the risks there are if one of the local government departments or one of the stakeholder bodies takes it over," said Mr Darby.

"We have spoken to Lord Shaftesbury and in principle he is interested in the option of selling.

"The price is one thing but it is also about liabilities and risks in terms of negotiating the cost."

The partnership believes the single solution is for a government department to set up and lead a taskforce, in conjunction with stakeholders, to reverse what it described as the "neglect" of statutory agencies over the past 20 years.

But that would require a functioning Northern Ireland Executive.

The Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs says Lough Neagh's problem is a complex, multi-factoral issue that will take years, if not decades, to solve.

"Part of that solution is to review the impact of current policies and interventions and exploring what we can do better in the short, medium and long term," said a department spokesman.

"This needs to be informed by science and evidence, including lessons from those other parts of the world which are also grappling with this same problem, and working with partners to deliver better outcomes."

- Published4 October 2023

- Published30 August 2023

- Published6 July 2023

- Published28 June 2023