NI peace deals: A history of Northern Ireland political agreements

- Published

Prime Minister Tony Blair and Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Bertie Ahern sign the Belfast or Good Friday Agreement on 10 April 1998

The deal has been done, the register has been signed, the ministers appointed.

Northern Ireland has a devolved government once more - Stormont is back.

The deal between the DUP and the government is the latest in a long line of agreements, some of which have stood the test of time better than others.

We take a look at some of those deals, from the 1970s to the present day.

Sunningdale Agreement

Irish and British premiers Liam Cosgrave (second left) and Ted Heath (centre) were joined by Alliance leader Olivier Napier (far left), SDLP leader Gerry Fitt (far right) and UUP leader Brian Faulkner at the signing of the Sunningdale Agreement

As the violence of the Troubles spiralled out of control in the early 1970s the UK government took the decision to suspend the Northern Ireland Parliament - the devolved legislature dominated by unionists - at the start of 1972.

London aimed to get a new devolved government up and running, but on the basis of nationalists and unionists sharing power.

It published plans for this new Northern Ireland Assembly and executive at the start of 1973.

Months of talks were finalised with the Sunningdale Agreement in December 1973 - named after the Civil Service Staff College at Sunningdale in England where negotiations were held.

But the biggest unionist party - the Ulster Unionist Party - was badly split on the deal, and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was strongly opposed, as were loyalist paramilitaries.

The main nationalist party- the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) - supported it but the IRA continued its campaign of violence.

The new executive was set up in January 1974 but a huge campaign of civil disobedience later in the year - led by the Ulster Workers Council - led to its collapse in May.

Anglo-Irish Agreement

An effigy of Margaret Thatcher was burned at a rally opposing the Anglo-Irish Agreement

Unlike Sunningdale, the Anglo-Irish Agreement did not involve Northern Ireland's political parties.

It was a deal struck on 15 November 1985 between the UK and Irish governments, led by Margaret Thatcher and Garett FitzGerald respectively.

The agreement gave the Republic of Ireland a consultative role in Northern Ireland for the first time.

Both governments also committed to the principal that Northern Ireland's constitutional status could not change without the consent of the majority of its population.

The deal was widely rejected by unionists because of the role it gave to the Republic of Ireland and there were huge demonstrations including a mass rally at Belfast City Hall.

All of Northern Ireland's unionist MPs resigned in protest, leading to a series of by-elections.

The SDLP supported the deal but the IRA opposed it, condemning the Irish government for giving formal recognition to the partition of Ireland.

Good Friday Agreement

U2 frontman Bono posed with UUP leader David Trimble and SDLP leader John Hume at a concert calling for a Yes vote in the referendum on the Good Friday Agreement

After years of negotiations between political parties and the UK and Irish governments, as well as talks with paramilitary groups, the deal officially known as the Belfast Agreement was struck in the early hours of 10 April 1998 - Good Friday.

The date gave the agreement its alternative - and widely used - name.

It was a deal between the UK and Irish governments as well as between Northern Ireland's political parties and set up the assembly and executive at Stormont which have been restored by the most recent agreement.

Supported by the UUP, SDLP, Sinn Féin and Alliance, as well as a host of smaller parties, it was opposed by the DUP.

The assembly and executive were to operate on the basis of power-sharing between unionists and nationalists.

The agreement also created new links between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland - the North South Ministerial Council - and links between governments and devolved administrations across the UK and Ireland - the British Irish Council.

Other elements of the deal included reform of policing in Northern Ireland, the release of paramilitary prisoners and the amending of the Republic of Ireland's constitution to remove its claim of jurisdiction over the whole island.

The deal remains the basis of how devolved government operates in Northern Ireland today - but it has encountered many bumps along the road.

St Andrews Agreement

Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness became known as the Chuckle Brothers

There were a number of crises at Stormont after 1998 and in October 2002 the institutions collapsed after police raided Sinn Féin offices at the assembly over allegations of an IRA spy ring operating there.

Cue more years of talks to get things up and running again.

They culminated in a summit in October 2006 at the Scottish seaside town of St Andrews - famous as the home of golf and one of the UK's oldest universities.

The deal amended and built on the Good Friday Agreement without replacing it.

Sinn Féin agreed to support policing and the courts while the DUP committed to sharing power with Sinn Fein.

There were changes to how the first and deputy first ministers were chosen and a statutory ministerial code was introduced.

The deal led to the DUP's Ian Paisley becoming first minister and Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness deputy first minister - an extraordinary turn of events given the animosity between the two parties.

A photo of them smiling together at Stormont led to them being nicknamed the Chuckle Brothers.

Hillsborough Castle Agreement

Prime Minister Gordon Brown jetted in to seal the deal with DUP leader Peter Robinson (centre) and Martin McGuinness

Another element of the St Andrew's deal had been the prospect of policing and justice powers being handed from London to Stormont.

By February 2010 this had not happened - with the DUP opposed - and there were real fears Martin McGuinness might resign as deputy first minister, collapsing the assembly.

But a deal was struck at Hillsborough Castle - the official resident of the monarch in Northern Ireland - allowing a justice minister to take office at Stormont.

Stormont House Agreement

No agreement has ever dealt with every issue - and the legacy of the past continues to hang over every set of talks.

BBC News NI's political editor at the time, Mark Devenport, identified the issues of flags, loyal order parades and the past as three key sticking points for Stormont in the early 2010s.

They were the subject of failed talks in 2013.

By 2014 Northern Ireland's attitude to UK-wide welfare reforms had become an increasingly difficult stumbling block for the power-sharing executive, raising serious questions about whether Stormont could balance its budget and if changes needed to be made to the power-sharing institutions to make them more stable and effective.

The Stormont House Agreement of December 2014 - named after the Belfast headquarters of the Northern Ireland Office - struck a series of financial deals, including devolving corporation tax to Belfast.

It set up a number of agencies aimed at tackling the legacy of the Troubles as well as a commission on flag-flying and cut the number of assembly members and Stormont executive departments.

Fresh Start Agreement

Just a year later it was a case of déjà vu all over again with more talks over paramilitarism and welfare reform.

The name - Fresh Start Agreement - begged the question of what all the other agreements had been about.

New principles were put in place expecting politicians to work towards the disbandment of paramilitary structures, while an international body was set up to monitor paramilitary activity,

A mitigation package was put in place regarding welfare reform.

But the parties failed to break the deadlock over legacy issues arising from the Troubles.

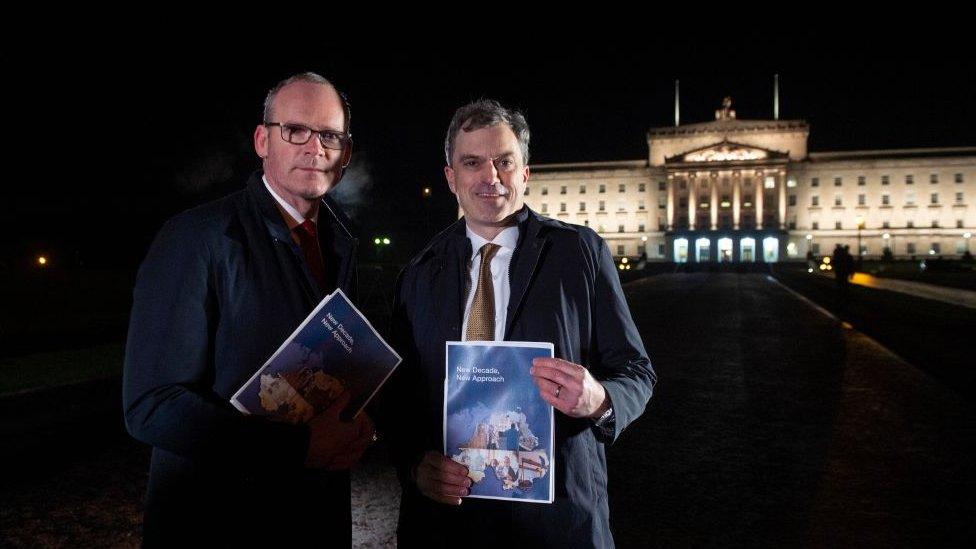

New Decade, New Approach

Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney and Northern Ireland Secretary Julian Smith held a press conference in the dark at Stormont to announce New Decade, New Approach

In January 2017 the Stormont institutions collapsed again - the catalyst was the DUP's handling of a botched green energy scheme which led Sinn Féin to walk out, although there had been tensions over several other issues.

After previous rounds of talks failed to produce a breakthrough, New Decade, New Approach was sealed in January 2020.

It included a commitment to legislate on the Irish language and to reform the petition of concern - a mechanism which could be used to block some legislation from being passed.

Other elements included a commitment to increasing police officer numbers and a commitment to a cash injection into public services from the UK government.