NI's government has returned Stormont - what you need to know

- Published

Michelle O'Neill was Sinn Féin's nomination for first minister, but Sir Jeffrey Donaldson is not deputy first minister

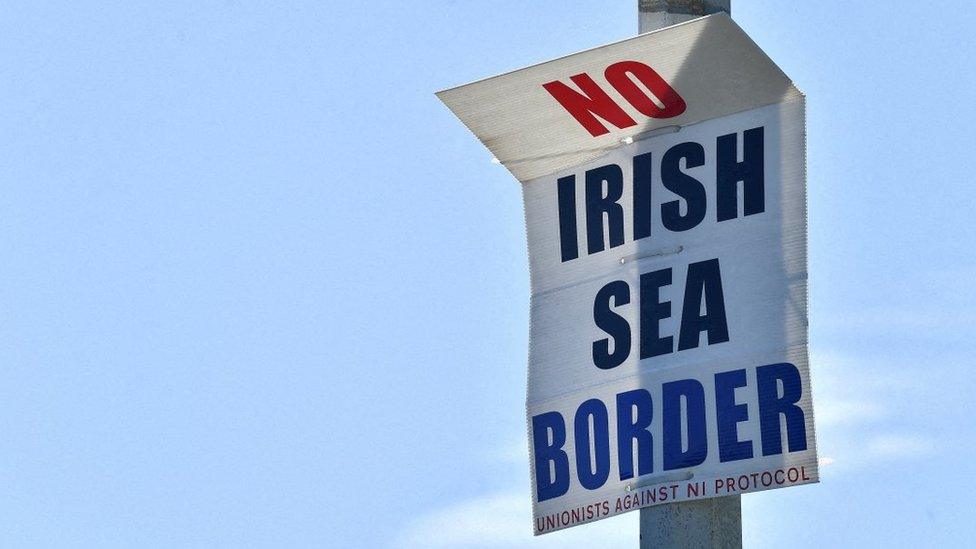

Devolved government in Northern Ireland has been restored after a 24-month hiatus, following a decision by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

It had been blocking the working of an assembly and executive over concerns about post-Brexit trade arrangements.

But the DUP agreed to re-enter the institutions after a deal which saw the government pass new legislation at Westminster.

On Saturday, assembly members gathered at Stormont to form a new Northern Ireland Executive, with Sinn Féin's Michelle O'Neill becoming Northern Ireland's first nationalist first minister.

Here's everything you need to know about how the return of power-sharing government in Northern Ireland works.

What is Stormont?

Stormont is the commonly used name to refer to the Northern Ireland Assembly, which is based in the Stormont Estate, in east Belfast.

The assembly is where laws are made and scrutinised by 90 elected representatives.

It was created in 1998, after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, which helped end 30 years of armed conflict known as the Troubles.

Stormont uses a system of government known as power sharing.

This has allowed nationalist and unionist political parties to share power together for the first time in an executive (or government).

Nationalists favour unity with the Republic of Ireland, while unionists want Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK.

When it is sitting, Stormont exercises powers over most matters, including the economy; education; health; policing and justice; and agriculture.

But certain areas - including international relations and defence - remain reserved for the government in London.

What happened when the parties returned?

After two years of stasis, they arrived back to work on Saturday after the assembly was recalled.

The government published the deal in full on Wednesday, and legislation to implement it was passed at Westminster on Thursday afternoon.

Sir Jeffery Donaldson gave a press conference at Hinch Distillery to say a deal between the government and the DUP had been agreed

The first order of business for members (MLAs) when they enter the assembly chamber is to elect a new Speaker - this had to happen before anything else.

The election of a Speaker requires cross-community support, so a majority of unionists and nationalists must vote in favour.

In 2020, Sinn Féin's Alex Maskey took on the role.

It has traditionally rotated between unionists and nationalists, and this time former DUP leader Edwin Poots was voted into the post.

What about the first and deputy first ministers?

Once the Speaker is elected, the parties entitled to jointly lead the executive - the body that makes decisions and policy in Northern Ireland - make their nominations.

For the first time on Saturday, Sinn Féin nominated a first minister because it won the most seats in the assembly election in May 2022, with Michelle O'Neill taking up the role.

The DUP, as the largest unionist party, nominated a deputy first minister for the first time.

When Sir Jeffrey became leader he said he would lead the party from Stormont and stood for election in May 2022.

He won a seat, but with Stormont down he remained at Westminster and Emma Little-Pengelly was co-opted into his Lagan Valley assembly seat.

She was nominated to take the post of deputy first minister.

The DUP previously held the first minister post from 2007 to 2017 and again from 2020 until 2022.

Although the titles are different, both offices hold equal weight and one minister cannot act without the other.

How were the other ministers appointed?

There are nine Stormont departments.

They are shared around the parties based on how many MLAs they have using the D'Hondt mechanism.

That led to Sinn Féin taking up three roles - Conor Murphy as economy minister; Caoimhe Archibald as finance minister; and John O'Dowd as infrastructure minister.

The DUP selected former first minister Paul Givan as education minister and Gordon Lyons as communities minister.

The UUP's Robin Swann resumed his role as health minister - a post he held up until Stormont's collapse in 2022 - and Alliance took the final role, Andrew Muir as minister for agriculture, environment and rural affairs.

One department - justice - is decided differently.

Policing and justice powers were not devolved until 2010, external, but the DUP did not want a Sinn Féin minister to be able to hold the post.

Instead it was agreed any justice minister required a cross-community vote.

Alliance has held the portfolio for every year of devolution bar the 2016-2017 mandate, when independent unionist Claire Sugden was asked to take on the role after Alliance decided not to be part of the executive.

Its party leader, Naomi Long, was appointed as a returning justice minister on Saturday.

The SDLP, which as the fifth-largest party has eight MLAs and does not qualify to be be part of the next executive, went into opposition.

Is it back to business?

Yes, and there's already a long list of things to do after 24 months of political paralysis.

Civil servants who have been minding the shop at Stormont for nearly two years have met their new ministers to provide them with their day-one departmental briefs.

It is thought a meeting of the newly-formed executive will also take place relatively soon.

At the top of the to-do list will be sorting public sector pay.

Just a few weeks ago more than 100,000 public sector workers in Northern Ireland staged a mass walkout.

Nurses, teachers, transport workers, civil servants took part in the action as they have not received a pay rise in the last couple of years.

The new finance minister will need to set a budget for the new financial year in April and settle those disputes.

The next health minister will also face a plethora of problems - not least grappling with pay - Northern Ireland's health and social care staff remain the lowest paid in the UK.

Waiting lists for elective care have been steadily worsening for the last 10 years - a substantial, sustained, and recurrent funding package is needed to tackle the backlog.

- Published30 January 2024

- Published2 February 2024