Brexit and the border: Views of Donegal Protestants

- Published

The Irish border has long shaped opinion and challenged identity among border-based Protestants

It is almost a month since Brexit talks shone a spotlight on the Irish border but life in County Donegal's Laggan Valley goes on as normal.

This part of east Donegal is home to many of Ireland's minority Protestant population.

It is a community that knows how borders can divide people, allegiances and loyalties.

Border life has long influenced opinion and challenged identity in this area.

Stewart McClean is from the Donegal border village of Newtowncunningham, just a few miles from the Northern Ireland counties of Londonderry and Tyrone.

He is a member of the Protestant Orange Order and has always had an allegiance to Britain; he says the implications of Brexit will not change that.

"We are governed by the laws of the Republic of Ireland but we continue to have an allegiance to the United Kingdom," he said.

When the UK leaves the EU, this area of rural Donegal will be part of a new frontier, where the UK and EU meet.

Last month's Brexit talks between the EU and UK stalled amid the Democratic Unionist Party's (DUP) objections to proposals for the Irish border.

DUP leader Arlene Foster subsequently welcomed "substantive" changes to draft plans for Northern Ireland post Brexit but warned of "more work to be done".

The DUP does not want Northern Ireland border laws to be any different to Great Britain's.

After the partition of Ireland, many Irish Protestants felt cut off from their northern counterparts with whom there was a shared cultural, political and religious outlook

It is a stance Mr McClean shares.

He describes Brexit as a "wise decision by the people of the United Kingdom".

"It is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, there can be no difference," he said.

"There are other solutions to the border issue in terms of Brexit, one being that Ireland also leaves the EU.

"They (Ireland and the UK) joined the EEC (European Economic Community) on the same day because of their historic trade links and those ties are still as strong. Various options are open to Ireland."

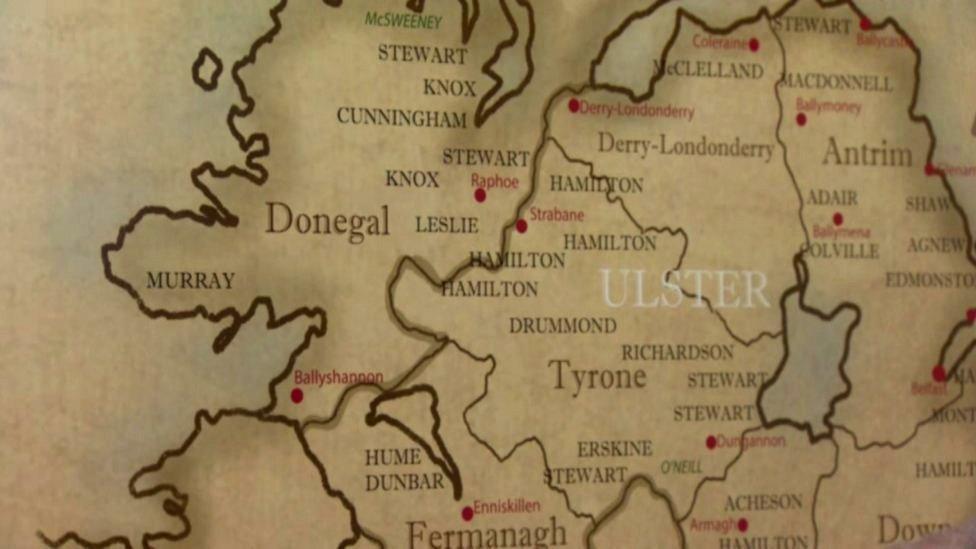

Back in the 17th century, Protestants settled in this part of Donegal during the Plantation of Ireland.

When Ireland was partitioned, many felt cut off from their northern counterparts with whom there was a shared cultural, political and religious outlook.

Mr McClean said the minority unionist/Protestant population has always been challenged by the existence of the border.

Stewart McClean believes the minority unionist-Protestant population has always been challenged by the existence of the border

"The border has been there since 1921 and every generation since partition has come through some difficulty.

"My grandfather came through the War of Independence, a time when leading Protestants in the town were interned. For my father, it was the Troubles of the 1960s and for my generation it was that latter part of the Troubles.

"But I have no difficulties with whatever is imposed on the border when the UK leaves the EU, the average person has always crossed the border without a problem."

He also said renewed border arrangements could present Donegal with an economic boom.

"Decentralisation in terms of the civil service will have to take place, jobs especially in terms of customs, will have to be relocated to Donegal," he said.

Retired school teacher Ian McCracken has lived close to the village of St Johnston all his life.

His family have farmed there for generations; he worships at the local Presbyterian church and has been involved in local Ulster-Scots community groups.

Ian McCracken believes the Brexit border issue is "not interlocked within a cultural or identity perspective"

His teaching career saw him cross the border daily to work in nearby Derry.

In terms of national identity, he sees himself as Irish.

He said the Brexit border issue is "not interlocked within a cultural or identity perspective" but focused more on the practicalities of ease of movement.

"As a family we were never made aware of being anything other than Irish, that was certainly not a unique thing and there would have been quite a few Protestant families who felt that way," he said.

"But there are also those who would have preferred the border to take in east Donegal."

The government says it does not want a return to border checks that existed during the Troubles

He said the border has taken many guises over the years and he has "experienced all the transitions from the rigid, fearsome line we had to cross, to the total freedom of passage".

"Certainly the older generation would be dreading the border that was in place in the 1950s - a punitive border that closed at 9pm and where you had to have your book stamped every time you crossed," he said.

Mr McCracken, who has researched the cultural and political views that shape the identity of Protestants along the border, believes post-Brexit concerns, however, are more focused on practicality than political rhetoric.

"There has always been a difficulty with identity here and people have often asked 'am I Irish or am I British?'

"There was a conflict, in the sense that to be Irish was to be viewed as nationalist in a political sense.

"But for many, the issue of identity is irrelevant in the context of Brexit and the border - the border will still be there as it has for so long. People are concerned more as to how it is going to interfere with daily living."

Following last month's talks between the UK and EU Theresa May said an agreement has been reached which will guarantee that there'll be "no hard border."

The details of exactly how this will work are still to be decided.

The UK is due to leave the EU on 29 March 2019.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published8 December 2017