David Cameron: Departed prime minister's role in Northern Ireland politics

- Published

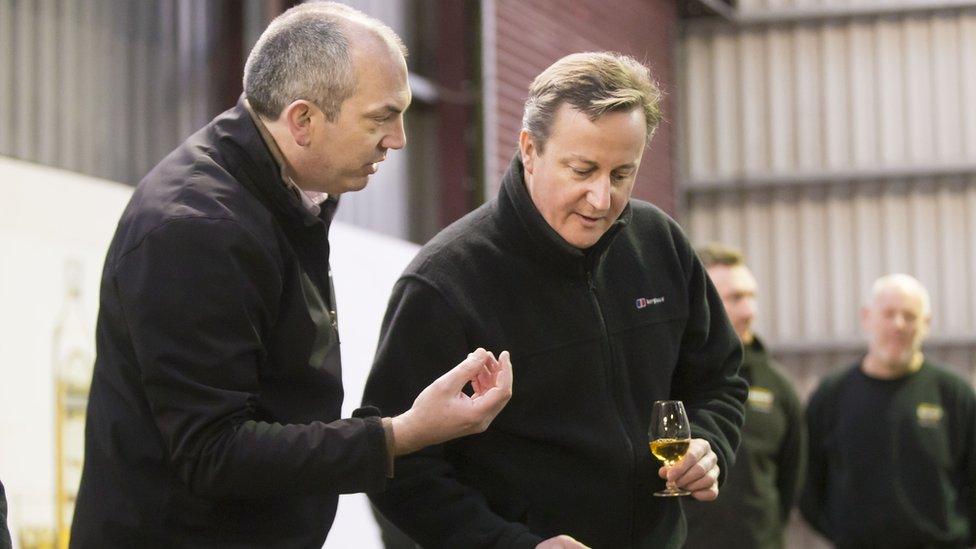

Is David Cameron's role in Northern Ireland politics one worth raising a glass for?

In his final appearance at the despatch box for prime minister's questions, David Cameron said Northern Ireland is stronger now than when he came to power six years ago.

But how will history judge his role in the region?

Mr Cameron has had quite a journey through Northern Ireland politics and his work began before his premiership.

As the leader of the opposition, he formed an electoral pact with the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in 2010.

He flew in to seal the deal, but the plan backfired for the UUP as they failed to secure a single seat.

After moving into No 10 Downing Street, Mr Cameron quietly let the relationship flounder, external.

The UUP, however, were reminded of the pact time and again by other Northern Ireland parties whenever the Conservative government introduced its spending cuts.

David Cameron struck a deal with the UUP in 2010, but let the relationship cool when the plan backfired

There are many, like former UUP communications director Alex Kane, who believe that experiment shaped Mr Cameron's hands-off approach to Northern Ireland.

"Had that delivered any seats, I think that would have changed the whole dynamic of his relationship with Northern Ireland," Mr Kane said.

"But it didn't, and in that moment I think it dawned on him that there are no votes for the Conservative Party in Northern Ireland."

Critical

Mr Cameron's first big test in Northern Ireland came five weeks after becoming prime minister.

He had to deal with the fallout from the Saville Report into into the events of Bloody Sunday in Londonderry in January 1972.

Fourteen civilians died after soldiers opened fire on a civil rights march in the city, and the report was heavily critical of the Army.

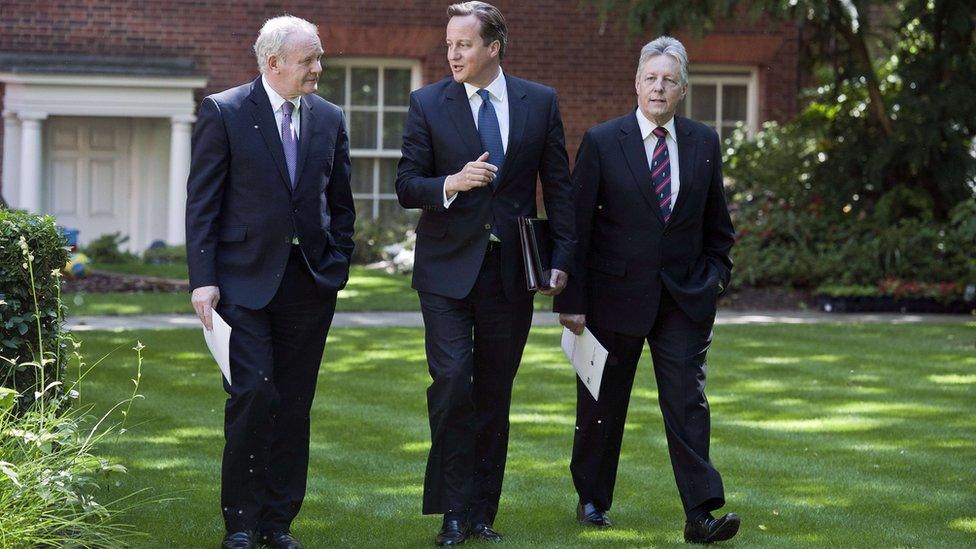

Mr Cameron's response to the Bloody Sunday Inquiry is said to have helped change the tone of his relationship with Martin McGuinness (left) and Sinn Féin

It was hard to stomach for Conservatives, and officials gave Mr Cameron his speech to respond to the findings the day before he was due to deliver it.

But it is understood he ditched it and instead wrote his own.

"There is no doubt; there is nothing equivocal; there are no ambiguities," he told the House of Commons.

"What happened on Bloody Sunday was unjustified and unjustifiable - it was wrong."

In Derry's Guildhall Square that day, the reception his speech received from a largely nationalist crowd was something no-one expected.

A Conservative prime minister was cheered and applauded by the families of the Bloody Sunday victims and their supporters.

He received great credit for what he said and many believe it helped to change the tone of future relations between the Conservatives and Sinn Féin.

But when the dust settled and the report was fully digested, some of the families changed their mind.

John and Geraldine Finucane wanted an independent inquiry into Pat Finucane's murder

Kate Nash, whose brother was killed, said it was a "fake apology".

"Although [the inquiry] found my brother and the others innocent of any crime, it also found the British government and up the chain of command innocent as well," Ms Nash said.

"It laid the blame at nine lowly soldiers.

"Any human being should have the courage to stand and tell the truth.

"He had a chance to be a great man that day and he missed that opportunity."

Stage

That was followed in 2012 by an apology to the family of murdered Belfast solicitor Pat Finucane after the publication of the Da Silva report.

Mr Finucane was shot dead by loyalists in front of his wife and children at his home in 1989.

The inquiry into state collusion around Mr Finucane's killing produced "shocking" results, Mr Cameron said.

But his apology was rejected by the family, who felt that he should have set up a full independent inquiry into the murder.

World leaders including Vladimir Putin and Barack Obama joined Mr Cameron for a G8 summit in Enniskillen

In 2013, Mr Cameron brought the G8 summit to Enniskillen's Lough Erne Resort in County Fermanagh.

The sight of the world's most powerful leaders lined up on the hotel's lawn is one that will live long in the memory.

The summit put Northern Ireland front and centre on the international stage, if only for a week.

More recently, Mr Cameron's relationship with some of the parties at Stormont had been strained because of his government's welfare reforms and austerity measures.

And it seems that voters in Northern Ireland have mixed feelings about his contribution to the region's politics.

"I don't think he can actually claim any credit for what's happened in Northern Ireland - the foundation was already there for change," one person in Belfast said on Wednesday.

But another added: "I don't think he was as bad as he was made out to be.

"I hope [his successor Theresa May] keeps doing the good job that Mr Cameron did."

- Published13 July 2016

- Published13 July 2016

- Published13 July 2016