What will NI parliamentary boundary changes mean?

- Published

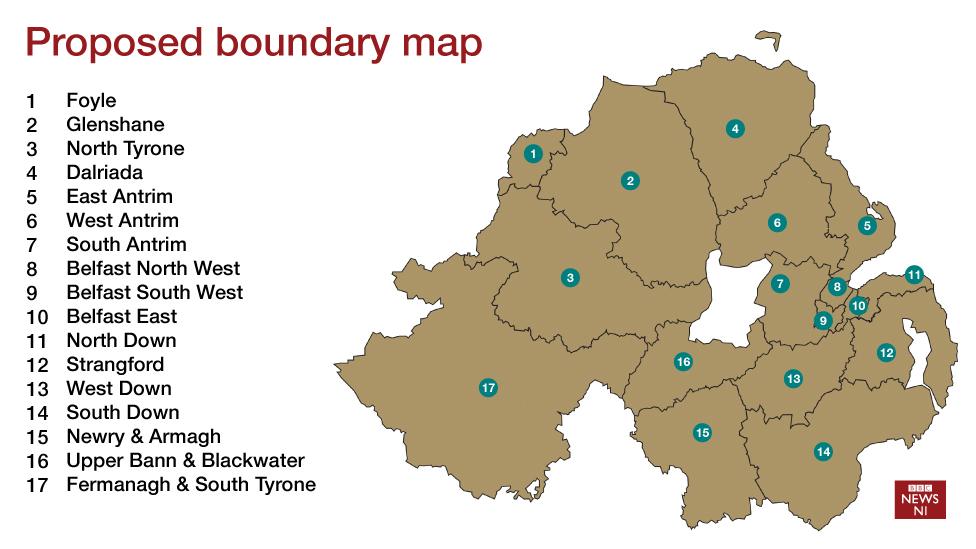

There are currently 18 Westminster constituencies in Northern Ireland

The proposed new parliamentary boundaries for Northern Ireland will cause more dismay than delight among political circles.

The Boundary Commission does not have an easy task.

The constraints imposed by the law are very tight - each seat must be composed of the rough building blocks of the new local government wards, to reach the designated number of voters with only 5% leeway.

Previous revisions were allowed much greater variation, which led to some anomalies but did tend to mean less disruption.

It could have been worse.

A proposed reduction from 18 seats to 16 was killed off at the last moment in the last parliament due to a row inside the then coalition government.

Drastic

But the legislation put in place then has not been repealed, so the goal of reducing the overall size of the House of Commons to 600 seats remains.

Thanks to changes in the electoral registration process across the water, Northern Ireland now loses only one seat rather than the two that would have been abolished in 2012.

Even so, the changes are drastic.

Every constituency is changed, in some cases changed utterly, as Yeats might have put it.

Fermanagh and South Tyrone, narrowly won by former party leader Tom Elliott in 2015, loses Dungannon town and instead acquires less Unionist-friendly territory to the west

Banbridge and Carryduff will be united in the new West Down constituency; the new North Tyrone will sweep from Strabane to Lough Neagh, swerving to include Omagh; the ancient kingdom of Dalriada is resurrected in parliamentary form, pivoting between Coleraine and the Glens; sandwiched between Dalriada and North Tyrone, a new Glenshane seat links Limavady and Magherafelt.

The SDLP will not be happy.

South Belfast, which their former leader, Alasdair McDonnell, retained in 2015 with the lowest ever vote share of a successful Westminster candidate, is to be divided four ways, mostly between an expanded East Belfast and a new South West Belfast.

The SDLP's two other seats, Foyle and South Down, are barely changed, but this may be small comfort.

The UUP also have little cause for cheer.

The River Lagan is the new boundary in East Belfast

Fermanagh and South Tyrone, narrowly won by former party leader Tom Elliott in 2015, loses Dungannon town and instead acquires less Unionist-friendly territory to the west.

South Antrim, the UUP's other 2015 gain, loses its northern half to the new West Antrim seat and stretches south to include the urban core of Lisburn, which was once solid UUP but has been much better for the DUP of late.

The DUP may therefore be able to make a strong challenge in both the new South Antrim and West Antrim.

Tougher defence

They also look strong in the proposed new East Antrim, Dalriada, Upper Bann and Blackwater, West Down and Strangford seats.

Elsewhere, however, the new boundaries are less good for them.

East Belfast, regained in 2015, becomes a tougher defence against the Alliance Party, with Dundonald out and the River Lagan as the new boundary.

North Belfast, transformed into North-West Belfast by the amputation of most of its Newtownabbey end and the shift of its boundary deep into the Lower Falls, will also be a tougher defence against Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin have most reason to welcome the proposed changes

And farther west, the old East Londonderry loses Coleraine town but gains Magherafelt; another tempting prospect for Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin have most reason to welcome the proposed changes.

Although West Belfast is to be split between the new North-West and South-West Belfast seats, the former now becomes a reasonable prospect, and enough of the core electorate remains in the latter to keep it solid territory.

Disruptive

The new North Tyrone and the barely changed Newry and Armagh look safe as well.

And as noted above, Sinn Féin have prospects elsewhere. (And Lady Hermon, the independent MP for North Down, is unlikely to be unduly troubled by the addition of Dundonald to her domain.)

For the Assembly, these changes will be very disruptive - not so much in terms of overall party balance, which should still end up proportional thanks to the electoral system, but in terms of the links between MLAs and their voters.

After consultation, the proposals must then be approved by the House of Commons

Some wonder whether it might not be better to link Assembly representation to the local councils, rather than to parliamentary seats which now face drastic revision every five years.

In any case, the planned reduction from six to five MLAs for each constituency means that the next Stormont elections will bring only 85 occupants to the blue chairs of the chamber, rather than the current 108, so the 2021 election will see major changes to Northern Ireland's political line-up.

The Boundary Commission's proposals will now be subject to public consultation, and must then be approved by the House of Commons where the government's slender majority depends on MPs who are being asked to abolish their own seats.

Northern Ireland's representatives are unlikely to come to Teresa May's aid for this purpose; Sinn Féin, the party which likely will benefit most from the proposals, is also the only party whose MPs can be guaranteed to be absent from the final vote.

- Published6 September 2016

- Published24 February 2016