Commemorations and commiserations

- Published

Belfast's "best-behaved baby"

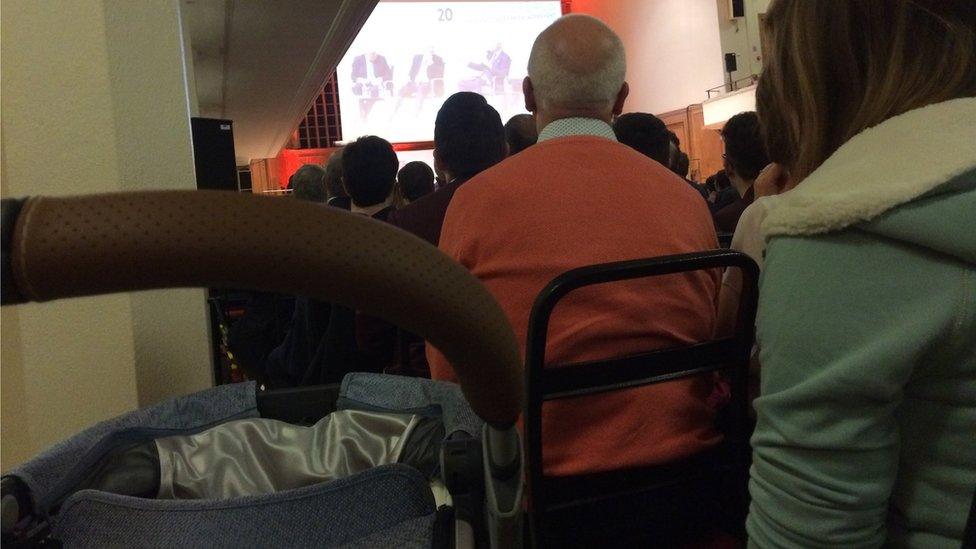

Twice this week I squeezed myself into a seat at the back of a packed room.

On Tuesday afternoon it was the Whitla Hall at Queen's University, I sat alongside students, school pupils, and politicians as Bill Clinton, George Mitchell and other leaders associated with the Good Friday Agreement urged the current generation to rediscover the optimism of 1998.

In the row ahead of me sat a young mother with what I can only describe as the best-behaved baby in Belfast, who didn't make a sound throughout several hours of fascinating proceedings.

On Thursday morning I was in the judicial review room at Belfast High Court. Here the benches were overflowing with victims of terrible abuse meted out in state and religious institutional homes in the seven decades prior to 1995.

Tuesday was meant to be a shot in the arm for our moribund political system.

Thursday amounted to a sobering reminder of the human cost of what the judge referred to as the "indefinite moratorium " at Stormont.

The victims are angry that they have been left penniless, despite a recommendation from a judicial inquiry that they should get financial redress or compensation from a minimum of £7,500 up to a maximum of £100,000 in the most severe cases.

The inquiry, chaired by Sir Anthony Hart, envisaged that the first payments should have been made by the end of 2017.

The victims feel they have been passed from pillar to post

However the planned compensation fell foul of the collapse of the executive in January 2017.

Since then, the victims feel they have been passed from pillar to post.

After months of fruitless political lobbying, one anonymous victim has now asked the courts to order either the Secretary of State Karen Bradley or the civil servants at the executive office to set up a compensation scheme as a matter of urgency.

The case, when it comes for a full hearing in September, should be an interesting test of the courts' view on what "residual powers" either the secretary of state or the Stormont mandarins might have at their disposal whilst the stalemate continues.

Mrs Bradley has stepped in on some matters, such as MLA pay or capping the costs of the controversial Renewable Heating Incentive scheme. But she has pronounced it "constitutionally difficult" to interfere in other areas, like the historic abuse compensation scheme.

Equally there is ambiguity about the limits to the powers of the civil servants.

Although it goes against their small "c" conservative instincts, the Stormont officials appear to have widened their scope for manoeuvre as the stand off at Stormont has continued.

As a sub plot, the secretary of state's reluctance to call a fresh assembly election also figures in the legal arguments.

The Northern Ireland Office admits Mrs Bradley is under a legal duty to set a date for an election, but they insist there's no time limit on when she should make her decision.

However the HIA victim's lawyers point to an excerpt from a previous ruling by the Law Lords which suggests there should be "no protracted stalemate, no persisting vacuum in the conduct of the devolved government" and the secretary of state would be expected to propose "a very early date for a poll".

Which brings us back to the Whitla Hall and the Queen's Good Friday Agreement commemoration.

An optimist might assume the Stormont parties will be so embarrassed at being called out by Messrs Clinton and Mitchell that by September they will have sorted out their little local difficulty.

So the victim's case would become academic.

The former First Minister Peter Robinson pointed a way forward when he talked about broadening out the issues the parties are dealing with. Instead of returning head on to their row about the Irish language, he believes the DUP and Sinn Féin negotiators might make more progress in a wider process which could provide "wins" for both sides.

Northern Ireland has been without a functioning executive since January 2017

There are other ideas around - using Westminster to wipe out the existing "red lines" (as favoured by Alliance) or setting up a shadow assembly (supported by the DUP, but opposed by Sinn Féin).

Both governments will no doubt explore these options in the weeks ahead.

However a dose of reality is needed.

The former Deputy First Minister Seamus Mallon provided it in part. He expressed his anguish at how - in his view - Northern Ireland has become divided into "silos". A pessimist might also recall that President Clinton previously appealed to the mourners gathered at Martin McGuinness's funeral to "finish his work".

Yet more than a year after that funeral oration, we still have no power-sharing government.

Making my way out of the Belfast High Court, I had to explain to more than one abuse victim in plain language what the legalese we had just been listening to meant.

"Yes, you have just jumped the first hurdle" I told them.

"But don't expect anything immediately - this will still have to be argued out in much more detail in five months' time, and then the judgment could still go either way".

Some rolled their eyes at the thought of waiting for yet more months.

Pushing through the security turnstile outside the Royal Courts of Justice, I remembered that some victims, like Clint Massey, could not be there because they died whilst waiting for Sir Anthony Hart's recommendations to be put into practice. If our politicians can ignore Mr Massey's emotional dying plea, why should they listen to this week's entreaties from the class of 1998?