Loyalist paramilitaries: 'Once you join it's impossible to get out'

- Published

Loyalist paramilitaries are recruiting in significant numbers, says the PSNI

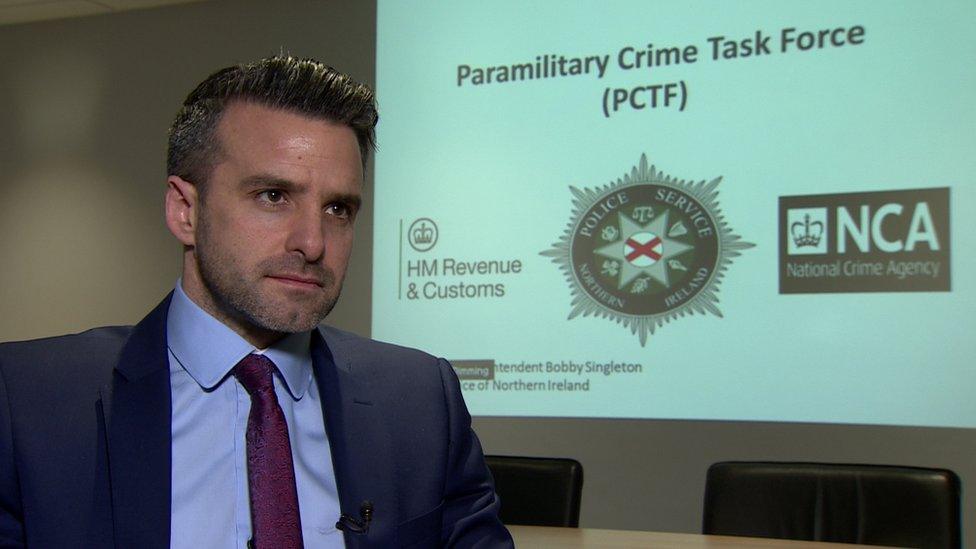

"It's effectively a life sentence - once someone joins a loyalist paramilitary organisation it's virtually impossible to get out," says Det Supt Bobby Singleton.

He leads the Police Service of Northern Ireland's (PSNI) Paramilitary Crime Task Force, a specialist unit set up two years ago.

It focuses on the activities of loyalists and the republican group the INLA, which are viewed as crime gangs.

Other PSNI units and the security service MI5 deal with dissident republicans because they are viewed as a threat to national security.

Almost a quarter of a century since they declared ceasefires, loyalist paramilitary groups continue to exist.

They also continue to recruit.

"In loyalist communities, we're talking about a significant number," says Mr Singleton.

People are being forced to join paramilitaries as a way of settling debt, says Bobby Singleton

"Young people are particularly susceptible to gang-type culture and obviously here in Northern Ireland we have a particular variation on that.

"So it is a problem for us and one I think will be around for the considerable future."

'They demolish lives'

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) remain heavily involved in a wide range of criminal activity.

They also continue to kill.

On Sunday night, Ian Ogle died after a savage attack in east Belfast.

His killing has been blamed on members of the UVF.

On Tuesday, four men were each sentenced to a minimum of 15 years in prison for the murder of Colin Horner in Bangor in May 2017.

Colin Horner was shot dead by a lone gunman in front of his three-year-old son

Police have linked that killing to an ongoing feud within the UDA.

Mr Horner's mother has said he was killed because he wanted to leave the organisation - she has pleaded with young loyalists not to join paramilitaries.

"Any young boys who think it's great to join these paramilitaries, please don't," she told BBC News NI.

"They don't destroy lives, they demolish lives."

'Only one way to get out'

While some join the UDA and UVF voluntarily, police say many are forced to join in settlement of debt they owe.

"That can start with something as simple as debts, whether that be money that's been borrowed or in some cases drug debt," explains Mr Singleton.

Colin Horner's mum Lesley warns young people not to join paramilitary groups

"Once you fall in debt to these organisations they determine how they want to see that repaid.

"In many instances that can involve you becoming actively involved in activity on behalf of those paramilitary groups.

"It could be holding weapons for them, it could be being involved in targeting or even the distribution of drugs."

Once in, members find it virtually impossible to leave and live in fear of being shot or badly beaten if they do, he adds.

"We would view many of the paramilitary-style attacks that we see as forms of coercive control being meted out by these organisations.

Ian Ogle died after he was stabbed 11 times in the back and had his skull fractured

"In many cases a lot of the young people who become involved with these organisations fear that if they don't go along with what they're told to do they themselves can be the victim of precisely those kind of attacks.

"What I have heard from some of the young people who have found themselves in that situation, and in fact some of the older members, is that they effectively can't leave.

"They've been told that the only way on occasion that they can get themselves out of an organisation is by buying themselves out.

"But then again, what guarantee does that come with that the knock won't come on the door at some point in the future and you won't be asked to do something on behalf of that organisation again."

'Legacy of negative narrative'

He disputes claims that while police know the identities of many members of the groups, they do not do enough to arrest and convict them.

Hundreds of people held a vigil at the scene of Ian Ogle's murder

"There is a distinction and there has to be one drawn between having information and intelligence and actually having evidence that can place people before the courts and can see them brought to justice," he explains.

"So yes, while we might have an idea who members of paramilitary organisations are, what's critical for us is actually obtaining the evidence that's necessary in order to have them effectively brought before courts and sentenced and convicted for the offences they've committed."

Det Supt Singleton says the task is made more difficult because many people are still afraid to provide evidence about paramilitary activity.

"We have to be realistic about this - there's still a culture within Northern Ireland that possibly the only thing more reprehensible than a terrorist is an informant.

"That is a legacy of the conflict that we've had here, it's a legacy of that negative narrative.

"I think that until we tackle that as a society, we as the police and other law enforcement agencies are always going to have challenges in terms of investigations against these paramilitary organisations."

- Published31 January 2019

- Published29 January 2019