Parting shots: The perils of ambassadorial predictions

- Published

Russia's transformation came faster than the UK ambassador predicted

"Prediction is very difficult," said the physicist Nils Bohr. "Especially about the future."

Nils Bohr was talking about the movement of tiny particles, but his adage also applies to the largest actors on the world stage.

Making accurate predictions in international relations is notoriously tricky, but that hasn't stopped many diplomats chancing their arm.

In their valedictory despatches - the last formal report a British ambassador would send back to the Foreign Secretary before quitting an overseas post - diplomats were encouraged to stick their neck out.

Time has shown many of these predictions to be wide of the mark.

Sir Bryan Cartledge sent his final telegram from Moscow in August 1988, when Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika was transforming Russia.

"I would expect a new political generation to accept the new political structure which Gorbachev has mapped out… This prognosis is nevertheless based on a timescale of twenty years, perhaps of a generation. I do not believe that Gorbachev and his allies can bring about a moral, social, psychological, political and economic revolution in the Soviet Union more quickly than that," Sir Bryan wrote from Moscow in 1988.

The ambassador thought Russia might still be communist in 2010. Of course, that was not to be. Fifteen months after that despatch was written the Berlin Wall came down. And, after just three tumultuous years, with revolution sweeping through the Eastern Bloc, the Soviet Union was dissolved - on Boxing Day, 1991.

Sir Bryan's despatch, formerly a classified document, is revealed in Parting Shots on BBC Radio 4. The Foreign Office released the document in response to a Freedom of Information request.

"Predictions are always dangerous", says Sir Bryan, who very graciously recited some lines from his despatch for the series.

"But ambassadors are expected to make them, especially in valedictory despatches. It's one of the things which ministers look for. They probably skip the rest".

Success v failure

Sir Bryan's despatch was prescient in part; he described the 1988 Communist Party Conference as "the Soviet Union's political coming of age - a qualitative change in its political life".

But he admits that forecasts elsewhere in the despatch were off-target: "I never thought that the Russians would take to a free market economy with such ease and enthusiasm as they have done."

"It's in the nature of people who go in for predicting things that they always make their worst case analysis", says Sir Rodric Braithwaite, who succeeded Sir Bryan as ambassador in Moscow.

"You can't get into much trouble if you predict disaster and it doesn't happen. What you can get into trouble doing is predicting success and then failure happens."

Sir Bryan says he has no regrets about his forecast. "On the political side, I don't think I did get it that wrong.

"After all, it's 20 years since I wrote the despatch; Russia is, after all, still effectively a one-party state. It still has large and active intelligence services, the successors to the KGB, both at home and, as we've seen recently, overseas."

Diplomats know they have only a slim chance of getting their forecasts right. "The only people who have ever been able to predict the future are Roman augurers by cutting up chickens" says Sir Rodric. "Otherwise there's no way of predicting the future."

'Unforeseeable disaster...'

That doesn't stop them trying. Lord Harlech, Britain's ambassador to the United States, wrote his valedictory despatch in 1965.

"I doubt whether we can expect much inspired leadership from the United States under [President] Johnson, but I would be surprised if he made many mistakes in reacting to situations not of his making … I think he is determined to avoid a dangerous escalation over Vietnam despite the temporarily more belligerent American behaviour in that part of the world," Lord Harlech wrote from Washington in 1965.

That "temporary" belligerence was in fact the start of Operation Rolling Thunder, the longest aerial bombing campaign in history.

"Barring some unforeseeable disaster" wrote Lord Harlech, "Mr Johnson is likely to preside over the fortunes of this most powerful nation on earth for eight more years".

Johnson, in fact, managed only three more years in the White House, departing in 1968 - by which point America had sent half a million troops to Vietnam.

In 1967, Sir Anthony Rumbold, Britain's ambassador to Thailand, confidently predicted that "the days of the coup d'etat are probably over for good".

Just four years later, Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn sacked parliament, abolished the constitution and imposed military rule. Since then, Thailand has experienced nine more coups and attempted coups, the most recent in 2006.

Some ambassadors, perhaps wisely, decided to play it safe instead.

"President Banda could, I believe, go on for as long as he lives or he could be assassinated tomorrow (nice easy non-prediction in a valedictory despatch - but the truth!)," wrote Sir Robin Haydon in Malawi in 1973.

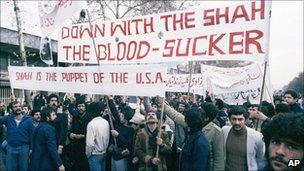

Protests against Iran's Shah in 1978 were underestimated by diplomatic staff

"Our visitors usually ask, in decent circumlocutions, when the Bahrain revolution will break out. The reply is that the revolution is not due for a year anyway and probably not for two: they should ask again next year, when they can expect much the same answer," Alexander Stirling wrote from Bahrain in 1972.

Some forecasts, however, had serious consequences. Diplomats concur that the Foreign Office's biggest blunder in trying to predict events abroad was in backing the Shah of Iran against the tide of the Iranian Revolution.

Sir Anthony Parsons wrote his valedictory despatch in January 1979, two days after the toppled Shah fled the country, never to return.

"We underestimated the capacity and will of the various elements to unite" wrote the ambassador in Tehran. "And we underestimated the weight and volume of hatred and resentment which had been welling up over the years."

Sir Anthony's despatches had helped convince the Foreign Secretary, David Owen, to side with the Shah against the popular uprising until the end - a stance that helps explain why many Iranians today still regard Britain as perfidious and ill-disposed.

The new series of Parting Shots begins on Wednesday 29 September at 1100 BST on BBC Radio 4.