The different tribes of Liberal Democrats

- Published

The big political parties have always been unofficial coalitions and it is becoming increasingly apparent that the Liberal Democrats are no exception.

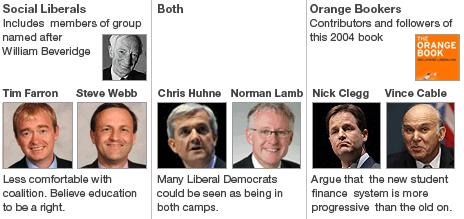

The fault line in recent years has been between those who are described as "orange bookers" - and those who see themselves as "social liberals".

The former are contributors to - or avid consumers of - the 2004 tome whose subtitle was "Reclaiming Liberalism". In essence, it argued for the party to be more economically, as well as socially, liberal.

One of its contributors - David Laws - denounced "soggy socialism" - and has subsequently argued that the publication began to shift the centre of gravity in the party away from big government solutions and from tax and spend.

The latter group are a mixture of those who see themselves as more "radical", along with some former members of the SDP. Some of these social liberals are also members of the Beveridge group, named after the Liberal who did so much to shape the welfare state.

They don't like a nannying government but they are equally critical of what they see as the market fundamentalism of some of their colleagues.

This latter group tend to be intrinsically less comfortable with the whole concept of coalition with the Conservatives - though many accepted the arithmetic inevitability of it after the election.

Amongst their number are those who in the past opposed a policy of "equidistance" between Labour and the Conservatives and would naturally have preferred, if pressed, a deal with Labour.

Their loyalty may have been more likely to have been assured had they been given a decent share of government posts in coalition, but only a very few have.

As the tuition fee vote looms, it looks increasingly likely that the Lib Dems will split three ways, and possibly four - with an attempt to call the whole thing off until next year.

There were moves "in the interests of unity" to get all Lib Dem MPs to abstain together, government ministers included, in line with the coalition agreement.

Ideological split

But as ministers such as Vince Cable were ridiculed for sitting on their hands instead of backing a policy that they had been allowed to shape, signals were sent out that many of them were unlikely to abstain after all.

This appears to have caused a potential rebellion to snowball, with possibly more than a dozen Lib Dem backbenchers likely to oppose a tuition fees rise rather than simply failing to vote at all.

At first glance the split could appear ideological.

The Lib Dems who have taken to the airwaves to argue that the proposed system is more progressive than the current means of financing higher education are those who wrote articles for the Orange Book - notably leader Nick Clegg and Business Secretary Vince Cable.

They genuinely believe that those who get most benefit from higher education should pay a contribution when they graduate and the more they earn, the more they should pay.

Beveridge Lib Dems still tend to cling to the idea that education is a right, not a privilege, and believe that any increase in fees - even though these are not paid upfront - would scare off people from modest backgrounds from going on to higher education.

If tuition fees signalled the start of an ideological split of this nature, it could spell trouble for the coalition - with many of the frontbenchers having to live with the prospect of regular rebellions from more "radical" backbenchers as the coalition takes further difficult decisions.

This, in turn, could mean that the Conservatives would suggest the Lib Dems were acting in bad faith, and might, as the senior partner, put Lib Dem-friendly policies into the legislative slow lane.

But in truth, the situation facing the Lib Dems is rather less straightforward than a philosophical difference of opinion.

The split isn't just between those in the Beveridge group and those who wrote the Orange book.

One of the Beveridge group's leading lights - Alistair Carmichael - is the Lib Dem whip responsible for getting the tuition fess policy through.

Meanwhile Charles Kennedy wrote the foreword to the garish 2004 publication, but - by all accounts - appears to be determined to vote against the rise in tuition fees.

And Chris Huhne is both in the Beveridge group, contributed to the Orange Book - and may be absent from Thursday's vote. He's currently on government business in Cancun dealing with climate change rather than with the heated internal debate in his party.

But in some ways a non-ideological dispute has potentially even more serious consequences for Nick Clegg.

Some Lib Dem backbenchers say the issue is at least as much about trust as it is about tuition fees.

They signed a pledge opposing a rise in fees, and simply do not buy the Clegg/Cable argument that, as they didn't win the election, they have had to accept compromises in coalition and have improved the system of student finance significantly.

They say that now, with a share of power for the first time in two generations at national level, they should be able to insist on more of their objectives - not fewer.

And they take the view that if the Lib Dems lose what was a unique selling point at the last election - that they could restore trust in politics and do things differently from Labour and Conservatives - then it may be a long time before they get a share of power again.

And while no doubt there will be some philosophical underpinning to any rebellion, some rebels may be more than a little motivated also by a straightforward political calculation. Julian Huppert represents Cambridge - a seat snatched by his Lib Dem predecessor from Labour in 2005, in the wake of anger over Iraq - and held in the wake of anger over tuition fees in 2010.

Awkward squad

He has signed the NUS pledge to oppose any increase in fees since the election and after the party went in to coalition.

If, as seems likely, the Lib Dems do split on this vote, some commentators will predict if not the death knell of the coalition, then the beginning of the end. But this would be over-dramatic. With the party already having plummeted in the polls, it's likely they will hang together rather than hang separately and hope that by the next election voters will be more forgiving, especially if they have other achievements to trumpet.

Party strategists say they do worry about an as yet unreported division - and that is not ideological, but practical. The split, they say, is really between those who have adjusted to government - who can compromise for the greater good and who will argue for apparently unpopular positions to try to change opinion rather than just reflect it - and those who feel more comfortable being in a protest group.

Despite all the fuss on fees there have already been some small backbench rebellions, for example on VAT, which have largely gone unnoticed.

On the other hand, the "protest group" may grow if others begin to share their overarching grumble that the Lib Dems are not getting enough out of the coalition.

This group would point out that as well as the VAT rise - which the party had campaigned against before the election - the commitment in the coalition agreement on Capital Gains Tax was watered down and they fear the government will backtrack soon on control orders.

So a more permanent awkward squad, already in embryo, might begin to develop - rather than a more serious breach in the coalition.

As Nick Clegg meets sceptical MPs on an individual basis before Tuesday evening's meeting of his entire parliamentary party, there are now also grumbles about the way the coalition document itself was negotiated.

The party's new President Tim Farron says that fees should have been a red line - with Lib Dems not settling for an opt out but insisting fees would not rise as a price of coalition. He is not opposed to changing the system of student finance but is highly likely to vote against the increase in fees this week.

So, it's a complicated tale... but there is a final twist.

It may have escaped some people's notice, but the official position of the party as whole - and as things stand, the policy on which they would campaign at the next election - is to scrap tuition fees entirely over a six year period.

- Published5 December 2010

- Published4 December 2010

- Published2 December 2010