Why the Church of England is a force for good

- Published

Has the Church of England protected Britain from narrow secular nationalism?

The influential political thinker Phillip Blond - creator of the concept of the "Red Tory" - argues that the establishment of the Church of England creates diversity in Britain and is vital to a true political plurality.

Should the state favour one Christian denomination over other religions?

Does this not mean a bias against people of other faiths or those of none?

And how can a Christian Church attach itself to a nation state and accept as its titular head a secular ruler?

Consider the established Church of England. Contemporary religious progressives will make common cause with atheists in seeking to disestablish the Church of England.

Both argue that the current situation doubly corrupts both the national constitution and the Christian religion.

Surely church establishment is an unjust anachronism which must now be abolished.

'Political legitimation'

This would free the secular state to be fully neutral and Anglicanism to be an independent religious body.

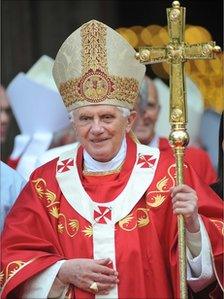

The Pope praised the Church of England during his state visit

It would not be tied to political control but liberated instead into its true nomadic Protestant destiny.

And do not better examples of church-state relations exist elsewhere?

In America for instance, where the separation of Church and State ensures a genuinely pluralistic society and a much greater flourishing of religions, since they are really freely chosen by individuals and exist outside the constraints of the state.

I hope to show that, on the contrary, church establishment in England creates a more diverse political and social life, prevents religious extremism and helps to minimise partisan conflict and secular violence.

We first need to realise that state religion is not a unique creation of Christianity. In fact, nearly all human polities throughout history have included a civil religious aspect.

Just as contemporary secular republics tend to promote civic worship of themselves, in the form of the people or the proletariat, so ancient polities also engaged in religion as political legitimation of their status quo.

To respect the gods was to respect the state.

It was Christianity which first gave us our sense that the political and the religious sphere should be distinct.

Christianity continued and radicalised the Jewish tradition that through the prophets had called the king to a righteousness that was not of his own making.

Christianity also universalised the Hellenic tradition that there was a good beyond being (Plato) or an ultimate virtue for which we should strive (Aristotle).

Tolerance

And the freedom that an established Christianity makes possible is the freedom not to be Christian.

Surely, though, you might say, the most effective critique comes from reason and not faith?

The separation between church and state is enshrined in the US constitution

I disagree.

As the current Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams has pointed out, any secular critique tends to absolutise or worship its own mode of criticism, because it is answerable only to itself.

Secular reason cannot criticise its own critique.

But religion can do this because it knows that human beings cannot ever do justice to the viewpoint of God. They always stand under judgement - even politicians, even kings.

Many religious people forget this fundamental insight and turn instead into fanatics. So isn't church establishment, which grants power to religion, likely to be a platform for such fanaticism?

Not so in my view. Britain's noble and historic tradition of being the most tolerant Western nation stems in part from the Anglican settlement.

Pope Benedict - speaking in Westminster Hall earlier this year - acknowledged that the official voice of faith had helped to create a Britain that has fought against most of the modern secular evils including the totalitarian ideologies of the 20th century.

Just as we need the church to protect the political, so we need it to protect the idea of civil society.

Today, churches and other religious groups have a crucial role to play in co-ordinating the revival of spontaneous citizens' activity.

If the establishment of the Christian church does not corrupt politics, then neither does it corrode Christianity.

On the contrary, its blurring of the boundaries between secular and sacred, reason and faith, have always themselves been to do with its powerful central insistence on the doctrine of the Incarnation.

This is accompanied by the idea that in Jesus Christ the heavenly and the earthly are so totally mixed up with each other as to be indistinguishable.

In other words, the message of Christmas.

The religious heart of the British nation has helped to prevent Britishness from meaning any sort of merely ethnic racial identity. It has helped to protect us from a narrow sectarian nationalism.

And the Church of England has generated a vast international Anglican communion which exceeds any mere Englishness.

If this country still, in all humility, wishes to contribute to global society and extend its centuries-old legacy of protecting and nurturing human civilisation, then it surely will not do so by abandoning that which it uniquely has to contribute.

You can hear a longer version of this essay in Blond on Britain which is on BBC Radio 4 on Wednesday 22 December at 2045 GMT. Or listen via the BBC iPlayer.

Here is a selection of your comments:

This is a lot of nonsense. Blond presents the arguments against religion, and claims to disprove them but fails to deliver any coherent counter arguments. If this is an example of the kind of critique that comes from faith, I am unconvinced that reason cannot provide a better one. What justification is there for the claim that "spontaneous citizens activity" is essentially linked to religion? "To respect the gods was to respect the state" - society has evolved and continues to evolve past such notions. And I don't think many of us would argue that America provides a shining example of church and state flourishing separately. You would be more likely to see a monkey than an atheist as US President. The Church of England can and does do good, the title of the piece is not inaccurate. But it is ludicrous to suggest that it is integral to every fabric of our society, as in truth it is irrelevant to many of us. Lisa, Kilmarnock, Scotland

Interesting analysis but flawed at the heart. First the Church of England does not represent the christian religion - it represents only its very narrow and self perpetuating version of it. It has systematically persecuted and in easier times killed christians who failed to adhere to its tenets. It luxuriates in its privileged position amongst all other Christian denominations by ensuring they never share in any of the areas it controls as its entitlement rights. Second it fails absolutely to make any real critique of the state and so perpetuates its colluded version of the so called tolerant England that is against inappropriate ideologies. It is far more bigoted than that - it aligns itself with an establishment class of people who may well have little or no belief but still can claim to be members of that Church. That is laughably described as Englishness whereas it is the ideology of the national elite imposed from above as in all totalitarian regimes - this is simply a little less extreme on the surface but scratch below and things are very different. Third this state church fails to extend reasonable rights to a large section of its own people - ministers of religion have rights that fall far below those all employees are entitled to. That stance not only has all sorts of privileged access to the political elite but also effectively consigns all other denominations ministers to the same fate even though they do not represent them in any way. I think there are some serious problems here, but why would anyone in the in group ever think there could be. G Barlow, London

The established church might be of benefit to the nation but it isnt of benefit to the church. It receives no funding or any other privilage from the state, Establishment is a serious disadvantage to the c of E, most non members think it is funded by the state and establishment encourages people to see the church as institution or heritage rather than an organisation that exists for faith. The CofE doesnt need to be established to see that the 'secular' world is also part of God's world. We dont even need establishment to enable 'civic religion' this happens not because of establishment but because people want it. increasingly councils do civic religion outside of the C of E anyway. Phil, Staffordshire

The main beneficial effect that our state religion has is that resists radicalisation and moderates those who follow it. I would argue that this is more about the manner in which it was set-up and the years of bloodshed following than simply its existence. There are several number of states with official religions that exploit said religion to curtail freedoms and resist politicial reform. Britain is the exception not the norm. Michael, London

It wasn't established Christianity that gave us the freedom not to be Christian. It was disestablished Christianity. Jewish people were allowed to return to live in England under Oliver Cromwell and his radical Puritan government. It was their non-conformist religious culture from which our tolerance sprang, not the stuffy institutionalism of the Established Church. Henry, Bedford

I am astounded at the sheer level of factual inaccuracy in this series of articles. For a start, British is not an ethnic or racial identity because there is no British race or ethnicity, religion does not come into it; Christianity was not the first religion to separate religion and the state - Zorastrianism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism are good earlier examples and atheists existed in Ancient Greek times - long before established Christianity. I could go on. Duncan, Oxford

All Mr Blond has done in this series of 'insights' has defended the status quo. I have no idea why you brand him a distinguished and influential political thinker, he just repeats age old establishment arguments. Time for some new thinking please. Horace, Billingshurst

As far as I can tell you have missed the point that me(as an atheist) and most of my friends (also atheists) have a problem fundamentally with the idea that religious people, who believe in some form of higher being with mystic powers, have input into a democracy which makes the rules which they must live by. Put yourself in my shoes and see that from an atheists point of view it is absolutely insane to make decisions based on an idea like faith. As I expect many people in the church doesn't want a world where no account is taken of the absolute morals which the church holds dear. The truth though is that most of the message which the church professes is one which I agree with, but i don't think this is because of belief in a some form of higher being but more because of the empathy which is fundamental in the churches teaching. Speaking from personal experience, empathy is certainly not something which atheists are unable to feel, far from it. So why would a secular democracy be any less empathetic to the human condition than a religious one. Also "If this country still, in all humility, wishes to contribute to global society and extend its centuries-old legacy of protecting and nurturing human civilisation". I can only assume that you feel that nurturing human civilisation is equivalent to spreading British philosophy as the correct way, then certainly we have been awfully good at that over the past centuries. My point is, start using that empathy which is so well regarded in the church for more than just emotions but also for attempts to understand other peoples thinking. Paul, Glasgow

"Secular reason cannot criticise its own critique." This is absolute rubbish. It would only be true if any criticism required a religious element. Secular criticism can provide all criticism that can be provided other than religious criticisms. But look at your own criticism of secular critique above. What is distinctly religious about it? Nothing: there is no predication of God, nor spirituality, nor faith, nor belief. The criticism only refers to the alleged nature of secular critique and is, thus, self refuting. Far from being necessary religious criticisms are profoundly useless: almost universally begging the question. Tony, London

What a complete fudge, everything is fine as long as we have blurry edges and no real firm commitment to anything in particular. The grand wizard druid and bishop of canterbury would surely agree, blending and blurring everything in Christendom and paganism seamlessly is his way after all. The only slight problem being that the book inspired by God and his supposed guide too, expressly forbids any such blurring and fudging, but hey he is far more intellectual than the author of the bible. If Jesus wanted to be a political leader in his day, who or what would have stopped him? if he had wanted to be made king, a fervent desire of many of his followers, who or what would have stopped him? If he had wanted to start a pseudo intellectual think tank to fudge and confuse who or what would have stopped him? His message was absolutely clear, He preached Gods Kingdom Government as the solution to all mankind's ills, he taught his followers to pray for said Kingdom/Government to come. He avoided being made King, and steadfastly refused to be drawn into the political arena, asked by Herod when being illegally tried, he stated clearly that his mandate to rule came not from any political or earthly organization but from heaven. Time and again he pointed to Gods coming kingdom as the source for solving all mankind's problems, indeed the scriptures clearly state it does not belong to man to even direct his steps.. let alone govern whole nations. The enormous mire the world is in provides bountiful evidence of just this one simple verse. Do these people and I include the Bishop/wizard/druid in this even pick up the bible and read it? I fear the answer is obvious, their reasoning is clearly higher than Gods, Ps 83 v 18. Hanran

- Published17 December 2010

- Published10 December 2010

- Published26 November 2010

- Published23 November 2010

- Published3 November 2010