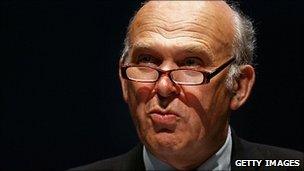

Profile: Vince Cable

- Published

Vince Cable has had a long and complicated political journey

Vince Cable, despite his recently found fame, remains an enigmatic character.

He is not a man given to emotional outbursts or shows of passion.

But the Liberal Democrat business secretary is at the centre of a political whirlwind right now.

In comments recorded by undercover reporters from the Daily Telegraph, Mr Cable says he has "declared war on Rupert Murdoch" and plans to block the media baron's efforts to take full control of BSkyB.

The remarks have led to him being stripped of his powers to make a decision on the bid - and were criticised by Downing Street as "totally unacceptable and inappropriate", although he will remain as business secretary.

In the recordings Mr Cable also spoke of an ongoing "battle" to curb the Tories' ideas and promote his own party's. He even hinted that he might take the "nuclear option" and resign if the Lib Dems do not get enough of their own way.

Such an act of self-sacrifice would follow one of the longest ascents to political power imaginable.

Now 67, he was a contemporary of the likes of Ken Clarke, Michael Howard and Norman Lamont - some of the Tory "big beasts" of the 1990s - while at Cambridge University.

But, while they enjoyed a reasonably rapid journey to influence at Westminster, the struggle for Mr Cable was long and complex.

A grammar school boy from York, he initially joined the Liberal Party but, after university, defected to Labour. He fought for the Glasgow Hillhead seat at the 1970 election, losing. As a Labour councillor in Glasgow he contributed to The Red Paper on Scotland, edited by Gordon Brown in 1975.

Parliament, at last

In 1982, Mr Cable changed party once more, this time opting for the newly formed Social Democratic Party. He made failed attempts to run for Parliament in 1983 and 1987.

After the SDP and the old Liberal Party merged to form the Liberal Democrats in 1988, Mr Cable was unsuccessful in another bid to become an MP in 1992.

It was not until the anti-Tory landslide of 1997 that he finally won the seat of Twickenham, south-west London, which he holds to this day.

Nick Clegg took over as Lib Dem leader after Vince Cable's stint as a stand-in

Along the way, he worked as an economics lecturer, at the Foreign Office, as a special adviser to future Labour leader John Smith, an official in the Kenyan government and as chief economist for the oil company Shell.

It is fair to say Mr Cable has travelled a bit.

Once in Parliament, his political career went comparatively smoothly, with promotion to the Lib Dem front bench in 1999 and to Treasury spokesman in 2003.

In this influential role he made pronouncements on the unsustainability of Labour's long economic boom - comments which saw his reputation rise following the arrival of the credit crunch. He was also one of the first senior politicians to call for Northern Rock to be nationalised.

Mr Cable helped to oust Lib Dem leader Charles Kennedy in 2005, but it was after Mr Kennedy's successor, Sir Menzies Campbell, resigned after two years in the job, that Mr Cable became a household name, at least among those with a modicum of interest in politics.

Having been elected deputy leader, he stood in at prime minister's questions and in a memorable exchange mocked Gordon Brown, remarking on the "prime minister's remarkable transformation in the last few weeks from Stalin to Mr Bean, creating chaos out of order rather than order out of chaos".

The laughter rang around the Commons chamber, emboldening this previously rather dry figure. Mr Cable, a naturally shy man, was enjoying himself in public.

He has hardly been out of the media since.

He was one of the few big-hitters among the Lib Dem leadership and when no party won overall control of the Commons after the 2010 election there were suggestions he might become chancellor under the Tory-Lib Dem government.

However, the job went to George Osborne and Mr Cable was given the business brief - in charge of a department he had previously suggested should be abolished.

Since then, government has proved far less easy than opposition.

Mr Cable's highest-profile task has been oversee the controversial rise in university tuition fees to a maximum of £9,000 a year.

This came despite the Lib Dems signing a pre-election pledge to oppose any such move, which has made him and party leader Nick Clegg the focus of much anger.

Mr Cable voiced doubt about whether he should back the plans in Parliament. Eventually he and all his Lib Dem ministerial colleagues did so, in the face of a large rebellion by the party's backbench MPs.

Mr Cable has been more certain in backing the coalition's deficit-reduction programme, but made some occasionally confusing comments.

At his party's annual conference in September, he criticised capitalism itself, accusing it of killing competition, baffling many of the Lib Dems' Conservative partners in government.

Indeed, the conflict between big ideas - rather than the day-to-day grind of politics - seems to animate him most.

His comments to the undercover Telegraph reporters are less surprising in this context.

He was recorded calling the coalition's attempts to push through changes in the health service, local government and other areas a "kind of Maoist revolution", which was "in danger of getting out of control".

Marriages

Opponents might accuse Mr Cable of inconsistency, some going on to question his reliability and willingness to take collective responsibility for government decisions.

Supporters might call it a refreshing independence, born of decades of intense intellectual activity.

Mr Cable has occasionally seemed ill at ease in coalition with the Conservatives

There is, though, little doubt Mr Cable appears to enjoy being a big figure in politics, whatever his travails.

Occasional glimpses of the private man come through too.

Mr Cable is an accomplished ballroom dancer, who will be appearing on a Strictly Come Dancing Christmas special. His detractors say such exuberant activity is insensitive at a time of austerity, but others argue that attempts to humanise politics can only be a good thing.

He is also a father of three grown-up children by his first wife, Olympia, who was from Kenya.

Even here, Mr Cable bucked 1960s convention by a mixed-race marriage, despite opposition from his father, who told him such unions "didn't work".

After Olympia was diagnosed with cancer for a second time in the 1990s, he combined the roles of being an MP and her carer until her death in 2001. Mr Cable remarried in 2004.

Mr Cable said he "fully accepts" the decision to strip him of his powers - he had said earlier he had no intention of resigning from the government. Whether, given his remarks about Rupert Murdoch, Mr Cable's future is in his own hands remains to be seen.

- Published21 December 2010