Government art collection: What the minister saw

- Published

A portrait of Queen Elizabeth I hangs in Ken Clarke's office

New cabinet ministers face many crucial decisions when they start their job.

Appointing key staff and deciding on priorities for the department are usually top of the list.

But within their first few weeks, they will also be asked to make another, much more personal decisions - about what art to hang on their office walls.

Ministers have access to the vaults of the Government Art Collection.

They can choose from beautiful and valuable works from 16th Century portraits of Elizabeth I to contemporary works by Howard Hodgkin and Grayson Perry.

But before they become ministers, many do not even know about this perk of high office: Liberal Democrat Energy and Climate Change Secretary Chris Huhne had no idea.

But their choices can be immensely revealing and in BBC Radio 4's What the Minister Saw we speak to Mr Huhne and two other cabinet ministers about their choices - and what their taste in art says about them.

'Rather marvellous'

Ministers' private offices are their inner sanctums, and what they choose to hang there can say a great deal about them, their personal preferences and how they see themselves.

Chris Huhne has among the most up-to-date taste in government.

Everything on his walls is modern, and some works are quite strikingly abstract.

Some have seen it as a political statement, but he does not.

"This building has recently been re-vamped and it's very white, very bare walls," he says, "and I thought actually it needed a bit of colour, and therefore modernist painting would be exactly what would be required to liven the place up a bit… I don't think it says anything about me."

But he does find the works he has chosen therapeutic, and makes a strong case for the importance of art.

"It gives me a great pleasure actually to see these pictures when I come in in the morning, and they are, I think, rather marvellous. I think that it's a good idea to have an environment where you can think and do things, and I think that art does help in that sense because it is one of the most distinguishing features of any society is its art."

'Difficult problem'

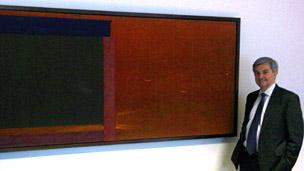

Justice Secretary Ken Clarke is, in many ways, the polar opposite of Chris Huhne.

As a member of every Conservative administration since 1974, he is deeply experienced in government.

His office is dominated by two Tudor portraits - of Elizabeth I and of her chief adviser, Lord Burghley.

Chris Huhne thinks modernist art 'adds a bit of colour' to his office

These pictures convey power and authority: What might they say to a visitor to Mr Clarke's office?

"Not that I'm reproducing the slightly dictatorial nature of Elizabethan government, I trust," he jokes.

"I really do think Queen Elizabeth was one of our most spectacularly successful monarchs. She was totally dependent on Burghley her Lord Treasurer for most of the time.

"He was a man of affairs, he was a man of government, a man of business and actually he was damn good at it."

It is hard not to be struck by the implicit comparisons there - perhaps Burghley is someone to look up to?

Ken Clarke laughs again.

"It's a marvellous thought that when I'm facing a difficult problem I gaze in front of my desk and think 'now what would Lord Burghley have done', but I don't think what Lord Burghley would have done would go down with the House of Commons, so I have to live in modern politics and admire a bit of history on the wall."

Departmental heroes

For International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell, office walls are an opportunity to push the work of his department.

Among the pieces on display are paintings of Disraeli, Pitt the Elder and the Duke of Wellington. It looks like Mr Mitchell might be a political junkie, but he demurs.

"These are the pictures which I selected, which mean something to me and which I think mean something to the mission which is behind all the work that the department for international development is doing."

He explains that in the 19th Century Disraeli, who he reveres, pointed out the gap between the rich and the poor in Britain, and says that that remains relevant for the work of his department in dealing with poverty around the world.

But then he points to a picture immediately above Disraeli, of another nineteenth century prime minister, one who is not normally a fixture on the walls of Conservative ministers.

"We've coalitionised the office because above Disraeli is a photograph of a very austere Gladstone, who of course was the champion of free trade, something which is incredibly important if the poorest parts of the world are to lift themselves out of poverty," he explains.

It seems art can serve any number of different political purposes.

What the Minister Saw will be on BBC Radio 4 at 1445 GMT on Sunday 2 January 2011. Or you can listen via the BBC iPlayer.

- Published3 December 2010