Lord Levy and Lord Sainsbury back party funding change

- Published

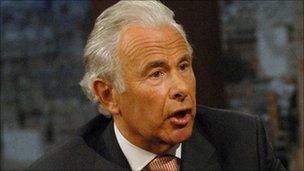

Lord Levy - let union members tick a box to donate

It is the dirty bit of politics that nobody involved really wants to talk about. Politicians like to give the impression they are incredibly busy saving the world.

But every so often they have to break off, and engage in the awkward business of begging for money. Or ask somebody to do it.

Enter Lord Levy. Tony Blair's fundraiser-in-chief was back in the political arena on Thursday.

He had come to give evidence to the Committee on Standards in Public Life, which is holding an inquiry into party funding. The conclusions of the committee's report, if adopted, could lead to a completely new relationship between politics and money.

Lord Levy's presence was a reminder of the explosive potential of this issue. He was arrested twice during what became known as the cash-for-honours affair.

Rich backers who had loaned or given Labour large amounts of money were nominated for peerages. Other parties also found they had some very uncomfortable donations to explain away. Nobody was ever charged and Lord Levy has always denied doing anything wrong and maintains that he never offered donors specific rewards in exchange for their political gifts.

On Thursday, he did give a fascinating glimpse into this secretive world. "People who have had success in life are the ones who can write out larger cheques," he told the inquiry. "Very few have purely altruistic reasons. They are driven."

"They wanted to meet the leader... does that give them access that they can use inappropriately? I think not... I never made a promise to anyone."

'Always be a question mark'

He described many aspects of his former role as "positive" for the democratic process. When he started raising money for Labour, he said the party did not operate on a "level playing field" with the Conservatives. Lord Levy saw his role as redressing the balance.

But the man who spent so much time trying to maximise Labour's donations now wants them capped for all parties. He said that even if donors genuinely wanted nothing in return for their gifts, political honours would always attract suspicion.

"If they are appointed to the House of Lords, no matter how ethical they (the donors) have been, there will be a question mark against their name," he told the Committee chairman Sir Christopher Kelly.

Donors often came to dinners hosted by Tony Blair and Lord Levy. But the former Labour fundraiser denies he ever promised specific access.

"I never did control the prime minister's diary," he said. "Any dinner I attended was a social evening discussing what was going on at the time. I never saw any access for commercial advantage."

Lord Sainsbury: Wants 85% state funding for parties

The coalition now shares Lord Levy's view that political gifts and loans need to be capped, to take away the merest suggestion that rich donors can buy influence. But limiting the ability of wealthy individuals to boost party coffers will throw up a number of tricky questions.

Parties need to be properly funded for democracy to work. If they have no money, they cannot develop decent policies. Nor can they explain these policies to voters. Some people might volunteer for parties, and campaign for free. But in the real world, big political organisations need funding to be credible.

But how much money do they require, and where should it come from? Another star witness at the inquiry on Thursday was Lord Sainsbury, who in the past donated millions of pounds to Labour.

Rather like Lord Levy, however, he has come to question the system within which he was once such an influential player. He told the committee that the current arrangements were "unfair", and that large donations were "problematic" for politicians and donors alike.

Lord Sainsbury proposed that political parties should get 85% of their funding from the state. The rest, he argued, should come from individual members who would be allowed to contribute a maximum of between £500 and £1,000 a year.

He urged the committee to recommend this in its report, as it could not be left to the parties themselves to hammer out an agreement. "Political parties are incapable of having a serious negotiation on this issue," he said.

'Obama effect'

But with such strain already on public finances, how do you explain to taxpayers that their increasingly scarce money is being channelled to political organisations they may not support?

Lord Sainsbury said the amount of money needed - about £50m a year - was a small slice of government spending. He said that such an amount was not a "make or break figure for such a fundamental issue in a democratic system".

There is certain, though, to be strong resistance to some models of state funding - particularly from smaller parties trying to establish a foothold at Westminster.

If big parties simply carve up a healthy chunk of state money, does that make them lazy? Would it further institutionalise the current structure, and solidify politics around the big three? Shouldn't the state always be separate from those organisations trying to change it?

One of the questions at the inquiry was whether state funding for parties would prevent an "Obama effect" in the UK - where a popular candidate can attract a surge of unexpected support, and sweep into office.

These are all big questions, before we even get to the issue of trade union funding for Labour. Any attack on that might be seen as a devastating blow for a party already struggling to fill its war chest. Lord Levy suggested that all union members tick a box which would determine which (if any) party gets their contribution.

The committee publishes its own ideas on political funding this spring. Then we can expect this debate, which has been quietly proceeding behind closed doors, to burst into the open again.

- Published3 November 2010

- Published8 July 2010