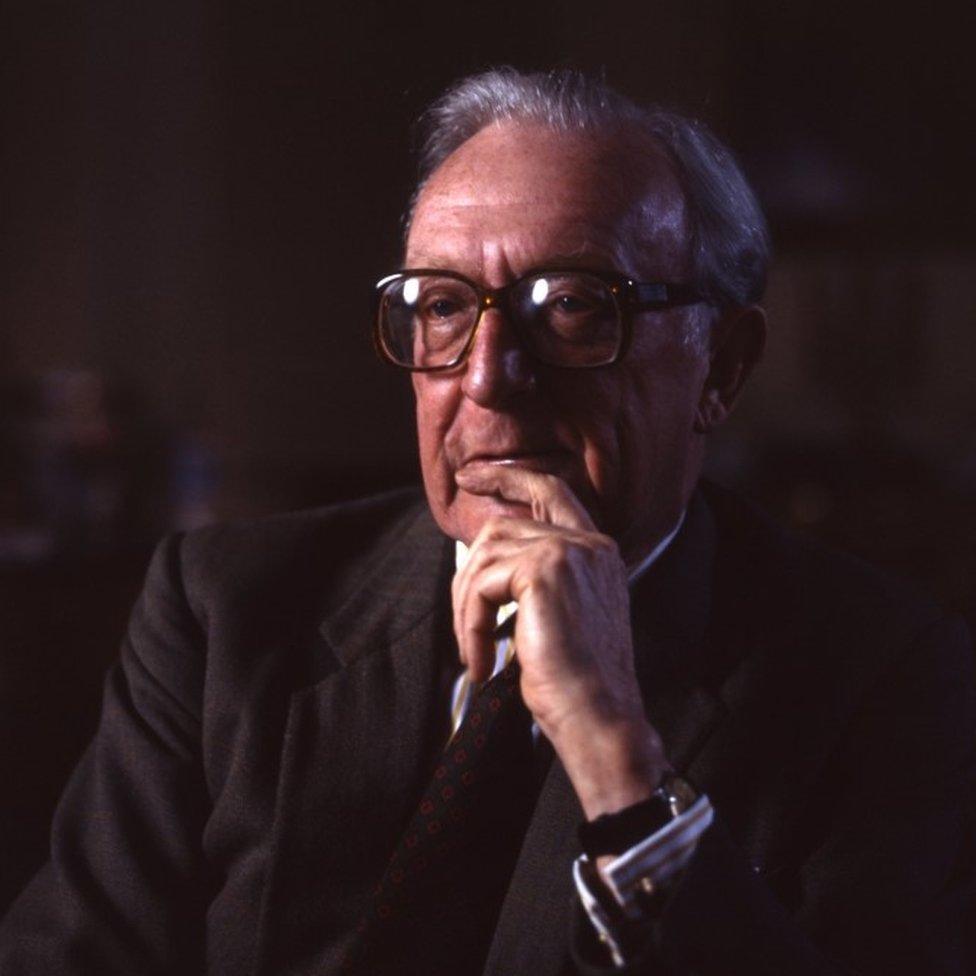

Obituary: Lord Carrington

- Published

Lord Carrington's political views were coloured by his experience of World War Two.

Like many of his generation, he had the desire to seek out a peaceful solution to conflict, an aim he followed throughout his career.

It also instilled in him a sense of honour and an acceptance that he would take full responsibility for his actions.

And it was this that led him to take the blame for the government's failure to anticipate the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentina in 1982.

Peter Carington - the family name, unlike the title, had only one "r" - was born on the 6 June 1919 and educated at Eton and the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst.

He succeeded to the title, as sixth Baron Carrington, on the death of his father, in 1938, and took his seat in the Lords on his 21st birthday, in 1940.

He served in the Grenadier Guards during the War, where he reached the rank of major and was awarded the Military Cross.

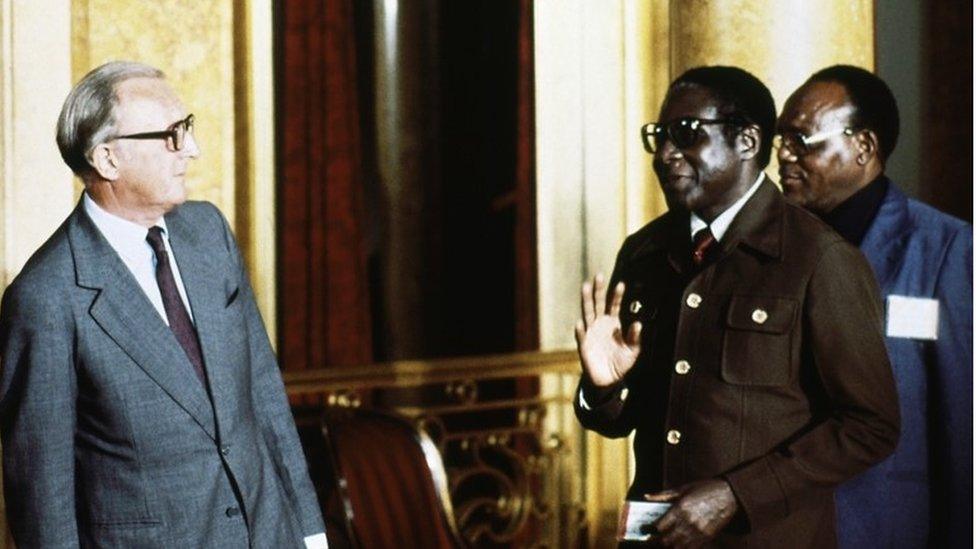

Lord Carrington chaired the Lancaster House talks that negotiated an independent Zimbabwe

Turning to politics after the War, he served as parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture under Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden before moving to a similar position in the Ministry of Defence.

In 1956, he was appointed high commissioner to Australia, a post he held for three years before returning to Britain and an appointment as first lord of the Admiralty under Harold MacMillan.

He became leader of the Lords in the government of Sir Alec Douglas-Home, moving to opposition leader when Labour won the 1964 general election.

He remained in that position until the Conservatives regained power in 1970, when the incoming Prime Minister, Edward Heath, appointed him as defence secretary.

It was Heath's government that took Britain into the Common Market, something Lord Carrington supported at the time.

Criticism

As someone who had experienced war in Europe at first hand, he felt that joining the EEC meant that future conflicts could be avoided.

He was later to express grave reservations over the way the EU had subsequently developed.

When Heath's government fell, in 1974, Lord Carrington returned as leader of the opposition in the Lords until Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979.

She made him foreign secretary, a job he later said he had always wanted but never thought he would get.

His first major task was to end the guerrilla war against Ian Smith's government in Rhodesia and pave the way for multi-racial elections.

The Lancaster House talks, which he chaired in 1979, brought the various parties together and led to the creation of Zimbabwe.

Lord Carrington was cleared of blame over the failure to predict the Falklands invasion

The Foreign Office came in for heavy criticism for failing to predict the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands, in April 1982, and Lord Carrington resigned as foreign secretary.

He was later cleared of any personal blame by the Franks Committee, which investigated government failures over the invasion.

Lord Carrington served as secretary general of Nato from 1984-1988, a time that saw the beginning of the end of the Cold War and eventually led to the break up of the Soviet Union.

In the early 1990s he became the EU peace envoy to the former Yugoslavia, where, together with the Portuguese ambassador Jose Cutileiro, he drew up a plan to try to prevent Bosnia-Herzegovina descending into war.

The plan was initially accepted by all sides - but the Bosnian Muslim leadership later rejected it.

His final mission, at the age of 75, was to mediate between the ANC and the Zulu Inkhata party, whose disagreements threatened the first multi-racial elections in South Africa.

He failed to broker an agreement but, just days after he left South Africa, the Inkhata leader, Chief Buthelezi, accepted the peace proposals.

After Tony Blair's Labour government removed the right of hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords, Lord Carrington was given a life peerage, enabling him to stay in the House.

As well as his political career, he was an active businessman, chairing the auction house Christie's as well as sitting on the board of a number of public companies, including Barclay's Bank and Schweppes.

He was made a Companion of Honour in 1983 and a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter two years later.