Expat veteran Harry Shindler fights for right to vote

- Published

Under UK law, expats who have spent more than 15 years abroad are denied the vote. But World War II veteran Harry Shindler is going to the European Court of Human Rights in an effort to change the government's mind. He explains the motivation for his battle.

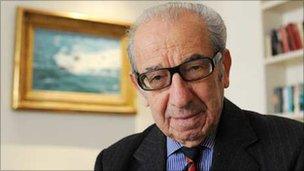

Harry Shindler says he and most other expats still feel part of the UK

Harry Shindler has what most of us would think of as an idyllic existence.

The World War II veteran lives in the beautiful eastern Italian resort of Porto d'Ascoli, overlooking the blue waters of the Adriatic.

Warm weather, friendly locals, good food, fine wine: life is good.

But Mr Shindler, a picture of healthy contentment at 89, is angry.

Like all other expats who have been out of the UK for more than 15 years, he has lost his right to vote.

Almost 70 years after his military service ended, he is going into battle again.

Mr Shindler wants the law changed, so that he can vote in general and local elections, and he is taking his fight to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

'Modest claim'

Sitting in his London club, on his annual trip back to Britain, he told the BBC: "We are talking about the principle of a man's right to vote. It's got nothing to do with time limits; it's to do with principle. You can't lay down conditions.

"Universal suffrage is set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Universal to my mind, and in every dictionary I've seen, means 'everybody'.

"There was a war to bring the vote to the people of Europe. We won the war, but some of the people who took part in the war, me included, are not allowed to vote themselves."

The European court is looking at the case, the UK government having entered its submission last week.

"We believe we have a very strong case," said Mr Shindler. "We are not asking, as France and Italy have done, for expats to get their own MPs.

"We are not going that far. We are very modest in our claim. All we want is the right to vote in elections."

It is estimated that 5.5 million UK citizens live abroad, but fewer than 13,000 had registered on UK electoral rolls by 2008.

Does this apparent apathy back up the government's argument that a "diminishing connection" with the UK over time means the 15-year limit is sensible?

Not according to Mr Shindler.

'Not Antarctica'

"At a time in the UK when there's great concern about participatory democracy, for the government to find reasons not to vote is curious indeed. One would think they'd be looking for reasons to get people to vote, because there is a danger to democracy if people don't vote.

"We feel we are part of the UK. We don't feel we're abroad at all. Distance-wise, I suppose if we were in the Antarctic we'd feel very much abroad, but when you are two hours away on the plane, you don't.

Allied troops liberated Rome in June 1944

"We have family and friends in the UK. You can't set a time limit on that.

"We use banks in the UK. We're members of clubs and institutions in the UK.

"Expats abroad pay their taxes at home. There are those who have property and haven't sold it because they believe they'll be coming back. They pay taxes on that property. They pay council tax.

"The pensions we get, government and private, come from the UK and those pensions, when they reach a certain limit, are taxed in the UK.

"So here we have expats who pay their taxes and are not allowed to vote. It's unacceptable."

Mr Shindler, a representative of the Italy Star Association for veterans, served for six years with the Royal Fusiliers and the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

He went to north Africa and took part in the allied landing at Anzio, in southern Italy, and the liberation of Rome.

Mr Shindler, who later helped set up and run the British Institute of Innkeeping, thinks the military service given to the UK by him and thousands of other expats strengthens his case and gives him "more right to speak".

Mr Shindler, who married an Italian woman after the war, moved to Rome about 30 years ago after taking early retirement.

The reason was to spend more time with his son and grandson, who had recently gone to Italy.

The law imposing a voting time-limit on expats was passed about five years later.

"They created a new kind of citizen in Europe - the disenfranchised - because not only can't we vote in the UK, we can't vote in Italy," said Mr Shindler.

"We, to all intents and purposes, are disenfranchised. There's thousands like that. That really is not allowable in a democratic union."

Mr Shindler thinks the costs of enfranchising long-term expats would be "nothing", with only "half a dozen" or so extra people voting in each constituency.

'Test for MPs'

The Council of Europe, which implements rulings made by the European Court of Human Rights, has called for an "unrestricted right to vote", suggesting expats could cast their ballots at embassies and consulates, if necessary.

Currently, most of those who take part in UK elections do so via postal votes or nominating proxies.

The Council of Europe, though, cannot force member nations to act. Ultimately it is at Westminster, not Strasbourg, where the law is decided.

Mr Shindler has lobbied MPs during his visit to the UK.

"A hundred years ago people fought for the vote and won," he said. "There were exceptions then. Females couldn't vote.

"Well, they threw themselves under horses and so on in their campaign. We don't intend doing that, but I don't think the MPs are taking enough interest in this."

A spokeswoman for the Cabinet Office, which co-ordinates government policy, said: "The length of the time limit has been changed over the years - from five to 20 years, then to 15 years from 1 April 2002, but on each time it considered the issue Parliament has accepted the view that generally, over time, a person's connection with the UK is likely to diminish if they are living permanently abroad.

"We cannot comment on individual cases. However, the government is considering whether the 15-year time limit remains appropriate. If a change is proposed, Parliament will need to reconsider the issue."

Mr Shindler said: "If this goes through, there'll be celebrations from Portugal to Poland, including Italy. It's a test for Members of Parliament. They have to demonstrate that they are backing us, otherwise all their talk is just chat. It doesn't mean anything."