Sentencing reforms: Will they work?

- Published

Ministers want to cut prison numbers by 3,000 by 2015

The coalition government has published its extensive bill for England and Wales aimed at reforming prisons, sentencing and legal aid. But what are the key elements on sentencing - and what impact could they have?

The Ministry of Justice spends almost £9bn a year on the courts, prisons and dealing with criminals. It must cut spending by almost a quarter over the course of this Parliament to meet its spending review targets.

Justice Secretary Ken Clarke said he wanted to do this by fundamentally changing the way the state delivers justice. He wanted to cut the costs of prison by reducing the population while, at the same time, improving the record on rehabilitating offenders.

But what's become clear is that the government's original estimate that demand for prison places would drop by 6,000 a year will no longer be met. The most important - and controversial - proposal to cut prison numbers has been scrapped.

At the same time, the government has decided it wants to keep some some serious offenders in for longer, rather than release them on licence.

In effect, and according to its own figures, the Ministry of Justice will probably find it impossible to cut the prison population below what it is today. But it could rise because we don't yet know the impact of longer sentences for serious offenders.

So that's more criminals off the streets - but at £45,000 a place per year, the costs are higher than for a year's education at a top public school. And that's the problem for the Ministry of Justice and its budget.

Public trust

When someone is in prison, they cannot offend. So if prison works, is it value for money when dealing with repeat offenders? It depends which way you approach the question.

Figures show that within a year of leaving jail, almost half of offenders are convicted of further crimes.

But the Ministry of Justice's own research shows there are differences in the rate of reoffending depending on what sentence a criminal receives.

Prisoners given sentences of between one and two years were more likely to reoffend than those sentenced to between two and four years, its research found.

But, at the same time, criminals given community sentences were less likely to reoffend than those jailed for up to 12 months.

Overall, the ministry admits that its own data isn't good enough to fully understand how well probation services do at rehabilitating a criminal in different contexts.

But alongside the reoffending data, there is also the question of public trust. The coalition believes that the current sentencing system has become too complicated, making it harder for people to have confidence that the right people are in jail.

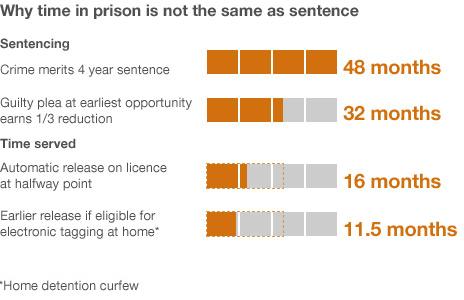

A judge starts with a sentence in mind, based on the specific circumstances of the crime and offender, the law and case precedents. That sentence can be reduced by up to a third for a guilty plea at the earliest opportunity.

Once jailed, prisoners given fixed terms serve half of their sentence behind bars. They are then automatically released at the halfway point to spend the rest of it on licence, under probation supervision in the community.

For instance, a prolific burglar initially facing four years might spend only a quarter of that time in prison because of a discount for an early guilty plea and early release on licence. The headline sentence in the news isn't the whole story.

Life prisoners and those given other special indeterminate sentences are treated differently.

Savings hole

So what are the key measures in the government's reforms? Last year ministers said they wanted to:

Use more community punishments and restorative justice programmes

Give a 50% sentence discount for pleading guilty at the earliest opportunity

Deport more foreign national prisoners

Stop remanding suspects who are unlikely to be later jailed

Reform indeterminate public protection sentences

Introduce payment by results for rehabilitation

These plans would, in theory, have led to massive savings.

The original plan to offer a 50% sentence discount would have reduced the prison population by around 3,400 by 2014-15 - a saving of £130m alone. Officials also believed the policy would have produced massive knock-on savings in the courts.

Prime Minister David Cameron has now killed that plan, saying it would be unacceptable to the public - which means that £130m saving has to be made from elsewhere in the justice budget.

Probation services are already being cut. If an offender cannot be supervised by a probation officer, then courts are more likely to send him to jail.

And that, in turn, may affect costs, reoffending rates and ultimately the ministry's ability to make savings.

Prime Minister David Cameron also says he wants an end to the automatic release at the halfway point for serious, sexual and violent offenders.

This is effectively a return to an old system. He also says he also wants "mandatory life sentences for the most serious repeat offenders."

These proposals are part of the tricky issue of indeterminate public protection sentences (IPPs). There are about 6,000 criminals who have received an IPP, which means they can be held beyond their original release date if they still pose a danger to society.

Only 5% of those have been released, showing how difficult it is to pass the tests - partly because some prisoners cannot get on the relevant rehabilitation course.

If these plans go ahead, the Parole Board will release serious, sexual and violent offenders only after they have served at least two-thirds of their sentence. The new mandatory lifers will also have to prove they are not a risk before they can leave prison. So, the number of these offenders inside will go up.

Foreign prisoners make up about 10% of those inside. Officials think they can make progress here and save another 500 places by the end of this Parliament. But it is a difficult business because some countries don't co-operate while some inmates argue they have a legal right to stay in the UK, such as if their family is here.

Another measure in the package, ending remand for suspects who won't ultimately be jailed, could save 1,300 prison places a year. So will the population go up or down? The aim appears to be to stabilise it.

- Published21 June 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published25 May 2011

- Published19 May 2011

- Published7 December 2010