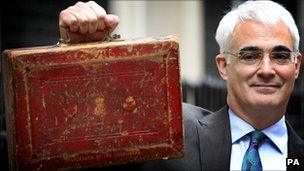

Profile: Alistair Darling

- Published

Mr Darling was one of Labour's survivors, in Cabinet under both Tony Blair and Gordon Brown

Alistair Darling has taken his time to deliver his verdict on Gordon Brown's turbulent period as prime minister.

While Lord Mandelson's memoirs were published within a matter of weeks of Labour losing the 2010 election and Tony Blair's followed soon after, Mr Darling has let the dust settle before making his views public.

During his 25 years in front line national politics, Mr Darling has never been known for his outspokenness nor his flair for the dramatic which makes his criticisms of Mr Brown - long suspected but previously kept to himself - all the more remarkable.

The tone of the comments in his memoirs are even more surprising since, as Mr Darling has himself acknowledged, the two men "go a long way back" and have a lot in common.

When Mr Brown handpicked Mr Darling to be his successor as chancellor in 2007 - when the former took over in No 10 from Tony Blair - it was the culmination of a long political relationship.

Like Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling spent his formative years in Edinburgh.

He attended the exclusive Loretto public school on the outskirts of the city and did his legal training in the city before representing it in local government and ultimately in Parliament.

Also like the former prime minister, Mr Darling rose quickly through the ranks of Scottish Labour before becoming closely linked with efforts to modernise the party in the 1980s.

But while Mr Darling has the air of a mild-mannered, non-confrontational Scottish lawyer, his political origins are actually somewhat more lively.

As a student activist in Aberdeen, he was associated with far-left policies and reportedly distributed "Marxist" leaflets at railway stations.

But after being elected to Parliament in 1987, he seemed to leave left-wing roots behind and his image was transformed from firebrand to troubleshooter.

'Safe hands'

After the party's 1997 election victory, Mr Darling served as chief secretary to the Treasury and then replaced Harriet Harman as social security secretary, following an almighty bust-up with her colleague Frank Field over policy.

He managed to bring an air of comparative calm to the situation, making a name for himself as a "safe pair of hands".

Colleagues remarked upon his lawyerly ability to master even complex briefs in quick time.

Mr Darling was parachuted into another "trouble" job in 2002, when Stephen Byers resigned as transport secretary amid the collapse of Railtrack.

Once again, he calmed the political row. Later, Mr Darling moved government policy towards an acceptance of road pricing, hated by many drivers. He is also remembered for pushing for the building of Crossrail, the multi-billion pound project linking east and west London.

In 2006, he moved to the Department of Trade and Industry, where he took a lead in suggesting that Britain's future energy needs may have to be met partly by a return to nuclear power.

'Forces of hell'

But none of the controversy he encountered up to then could have prepared him for his near three-year stint in No 11, however.

Mr Darling said he had "fundamental disagreements" with Mr Brown over economic policy

When his long-time political ally moved to 10 Downing Street in June 2007, Mr Darling, the quiet man of the cabinet, replaced him as chancellor.

Many commentators thought he would be a "yes" man, cowering in the shadow of his powerful boss.

But Mr Darling gradually appeared to grow into the job and staked out his independence when, in the summer of 2008 - and not long before the collapse of Lehman Brothers - he warned of the worst financial crisis in 60 years.

This resulted in a backlash from those close to Gordon Brown, with Mr Darling later famously remarking that the "forces of hell" had been unleashed on him.

Mr Darling proved a central and for many, reassuring, figure during the turmoil of the banking crisis but as the UK economy went downhill his relationship with his neighbour deteriorated.

Not reshuffled

For many the crunch moment came in the summer of 2009 when Mr Brown reportedly tried to remove him and promote his closest ally, Schools Secretary Ed Balls, to chancellor.

It was widely reported that Mr Darling threatened to resign if he was moved and, weakened by internal party divisions, Mr Brown backed down and Mr Darling remained where he was.

Subsequent arguments over how to reduce the deficit - and what level of spending cuts could be sold to the public shortly before an election - led to further tension.

After Labour's defeat at the polls and Mr Brown's resignation, the chancellor was talked of in some quarters as an interim leader but he decided to stand down from the frontbench in October 2010.

However, he remains a respected voice on the backbenches and, as the reaction to his memoirs has proved, one still capable of making the headlines.

- Published4 September 2011

- Published4 September 2011