Profile: Jeremy Heywood - the next Cabinet Secretary

- Published

Jeremy Heywood has been at the heart of decision-making in government for decades

Jeremy Heywood will replace Sir Gus O'Donnell, external as the Cabinet Secretary in the new year, making him one of the most powerful people in government, but who is he?

As one former Whitehall colleague puts it, he is "quite possibly the most important person in the country that nobody has ever heard of".

Nobody, that is, apart from all the ministers and prime ministers - from Norman Lamont to Tony Blair, Gordon Brown to David Cameron - who seem to have found Jeremy Heywood indispensable.

His new job as Cabinet Secretary, sitting next to the prime minister in Cabinet, will cement his position at the heart of the political establishment.

But he has already been there for years.

"If we had a written constitution in this country," quips former head of No 10 policy unit Nick Pearce, "It would have to say something like: 'Not withstanding the fact that Jeremy Heywood will always be at the centre of power, we are free and equal citizens'."

So how did Jeremy Heywood begin his influential but invisible rise?

"He was head boy. He didn't flaunt himself [but] he had the extraordinary knack of getting to know everybody and responding to different sorts of people," says Michael Allan, who taught the young Jeremy Heywood in the 1970s at Bootham school in York, an independent school founded by Quakers

Although his family was not Quaker, Heywood's father taught at the school - his mother was an archaeologist.

There was, his brother Simon recalls, plenty of parental encouragement to do well, which doubtless appealed to Jeremy Heywood's early competitive instincts, as he revelled in "beating all comers at chess and squash and general knowledge quizzes".

He moved on to challenge himself against Oxford's finest with a degree in History and Economics before beginning a swift ascent of the Treasury ladder in London.

'Preternatural calm'

Private secretary to Norman Lamont as Chancellor when barely 30 years old, he was caught up in the chaos of "Black Wednesday", external in 1992. Sterling was in crisis and Norman Lamont was forced to announce a humiliating withdrawal from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism.

That drama helped forge an early bond between Heywood and Lamont's young adviser at the time, one David Cameron.

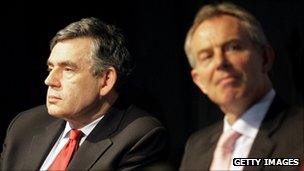

Jeremy Heywood played a pivotal role in maintaining links between Gordon Brown and Tony Blair

But Heywood's career, external has been far from tied to Conservative fortunes.

When Tony Blair took power in 1997, he brought in new appointments, such as his chief of staff Jonathan Powell.

Yet Heywood, who became private secretary in number 10, still made himself indispensable in a crisis such as 9/11. Powell recalls Heywood's "preternatural calm".

While many top politicians have found Heywood a reassuring presence, his reputation among his civil service colleagues has not always been so positive.

He was linked to a speech by David Cameron in March, describing civil servants as "enemies of enterprise".

"There were suggestions that Jeremy Heywood may himself have been one of the instigators of the speech," says film-maker and veteran Whitehall watcher Michael Cockerell.

Earlier, Heywood was involved in painful civil service change - such as Treasury budget-cutting and job losses in a major 1990s expenditure review.

At least one colleague was more enamoured. Heywood met his wife while working on this expenditure review, a classic Treasury romance perhaps, amidst the spreadsheets.

They now have three children. And a domestic haven may have been especially valued during the most turbulent part of his career at No 10, as the relationship between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown disintegrated.

Heywood, who keeps a bust of Gandhi on his office mantelpiece, was one of the few to maintain peaceful relations between the two camps.

But his role as Blair's private secretary in conducting government business has been questioned.

His critics have accused him of being complicit in the culture of "sofa government", external in Blair's Downing Street, citing evidence given to the Hutton Inquiry into the death of Dr David Kelly, external that some of the key meetings between politicians and officials were not minuted during that period.

Low profile

His years out of Whitehall as a banker between 2004 and 2007 have also drawn him into controversy.

When Southern Cross care homes came to grief recently, the press picked up on the fact that Heywood had a senior position at Morgan Stanley, external at the time the bank helped negotiate the company's financial arrangements.

It is understood that although he was co-head of the UK Investment Banking Division at the time, he was not personally involved in the negotiations.

When Heywood becomes cabinet secretary he will not be taking on the full role of his predecessor Sir Gus O'Donnell.

He is not going to head the home civil service. His focus will instead be wholly on the cabinet and policy. And sitting, as he has so often, right in the thick of things.

But is he too close to the politicians?

"There may be some sense in the civil service," says Michael Cockerell, "that Jeremy Heywood has lent too far towards pleasing his political masters".

And Nick Pearce, who worked closely with Heywood under the last Labour government, expresses both admiration and anxiety: "For somebody like me who believes in decentralising and dispersing power… you don't want one person to have so much power and influence, but I'm pleased it's him."

But Lord Lamont, who took on the young Heywood as his private secretary, rejects any criticism: "I think it would be quite wrong to suggest that Jeremy Heywood was any kind of yes-man for ministers."

We will clearly be hearing more about Jeremy Heywood. Not yet 50 years old, he could be in this crucial job for many years.

He will try to stay hidden, and avoid being the subject of debate. Downing Street told us there is no official photograph of this key figure.

But if you want to understand where power lies in British government, you have to picture Jeremy Heywood - right at the centre.

Radio 4's Profile of Jeremy Heywood, external was first broadcast on Saturday 15 October at 19:00 BST. Listen via the Radio 4 website, external or download the programme podcast, external.

- Published11 October 2011

- Published1 June 2010