Ken Clarke wants more secret hearings in courts

- Published

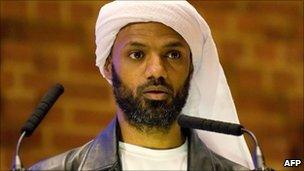

Binyam Mohamed: Fought long battle to discover what UK knew of his treatment

The government has published proposals to expand the use of secrecy in civil courts to protect national security.

Justice Secretary Ken Clarke said courts needed procedures to prevent sensitive secrets becoming public.

Campaigners against the move say the changes could be "truly radical and dangerous" for open justice.

The proposals , externalcome after former Guantanamo Bay detainees fought in the courts to see documents relating to allegations of collusion in torture.

The green paper suggests holding parts of similar future hearings behind closed doors so that a case could be argued without sensitive material becoming public. The proposals extend to inquests.

Ministers say they have considered creating a special national security court - but would prefer to allow ordinary courts to go into closed sessions.

Mr Clarke told MPs: "The problem is this. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number and diversity of judicial proceedings which examine national security-related actions.

"In many cases, the facts cannot be fully established without reference to sensitive material. But this content cannot be used in open court proceedings without risking serious damage to national security or international relations.

High Court in London: More proceedings could be heard in secret

"The consequence is a Catch 22 situation in which the courts may be prevented from reaching any fully informed judgment on the case because it cannot hear all the evidence in the case.

"It cannot hear all the evidence because it would do serious damage to national security if the evidence was available to all parties, and the public."

Mr Clarke said the government was left with "unsatisfactory choices".

"The Government is unable to defend its actions. Claimants are left without clear judgments based on all the relevant information. And the public are left with no independent judgment by the Court - because it has not been able to consider all the evidence."

Mr Clarke said the green paper consultation included proposals to increase the use of "closed material procedures" across the civil courts.

This would mean that the government could withhold sensitive information from a claimant, such as someone suing the government, but it could be argued about as part of the case by security-cleared lawyers behind closed doors.

This "special advocate" procedure is already used in a number of cases, such as deportations on national security grounds and challenges to counter-terrorism control orders.

The government attempted to use the closed hearings route in the damages claim brought by former Guantanamo Bay detainees. But in July the Supreme Court said it had no power to do so, external.

Massive settlement

The government eventually reached a substantial settlement with the men in return for them dropping their legal action.

At one stage, the legal action over Guantanamo Bay involved hundreds of thousands of documents and tense hours in court as government lawyers battled to avoid disclosing anything that could potentially compromise national security and relations with the United States.

Legal charity Reprieve, which spearheaded Binyam Mohamed's legal action to disclose evidence of his ill-treatment, said that had the proposals been in force a decade ago, he would never have won.

Clare Algar, director of Reprieve, said: "The Government is seeking to close off the very methods by which we first found out about UK complicity in torture and rendition.

"This Government came to power claiming it wanted to get to the bottom of Britain's involvement in torture. Instead, they are merely seeking to ensure that in future, whatever dirty secrets that are swept under the carpet stay there."

Isabella Sankey, director of policy for campaign group Liberty, said: "The security services seem to think that having to compensate former Guantanamo detainees for failing in their duty to them justifies closing down open civil courts into the future.

"These payouts should encourage the avoidance of complicity in torture, not blatant attempts to halt centuries of British justice.

"Further inroads like this will make it even easier for the system to be abused - to prevent embarrassment not protect national security."

Inquests secrecy

The government says it wants to extend secrecy to inquests which involve sensitive information or sources.

Under one proposal, jurors and family members of those who have died could be subjected to security vetting - an investigation into their backgrounds - before they would be allowed to see evidence relating to a death.

The move has been prompted in part by the case of Azelle Rodney, a London man shot dead by police in 2005. Police say they cannot disclose intelligence that led to the decision to open fire, leaving his inquest in legal limbo.