Hague backs closed hearings for intelligence cases

- Published

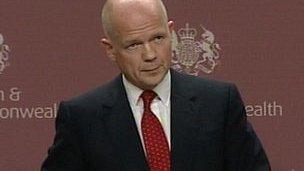

Foreign Secretary William Hague is responsible for the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6 and GCHQ

Foreign Secretary William Hague has backed plans to restrict what can be said about the security services in open court.

Sensitive national security information would be heard in closed courts under the plans, which have been criticised by campaigners.

In a speech, Mr Hague also committed to "drawing a line" under the alleged involvement of UK agents in torture.

Claims of the UK's alleged torture role have emerged in civil court cases.

Last year UK resident Binyam Mohamed, who was held in Guantanamo Bay, won his bid to disclose secret information relating to his alleged torture.

Mr Mohamed said the UK authorities knew he was tortured at the behest of US authorities after his detention in Pakistan in 2002.

Torture inquiry

Speaking on Wednesday in London, the foreign secretary said: "The very making of these allegations undermined Britain's standing in the world as a country that upholds international law and abhors torture.

"As a government we understand how important it is that we not only uphold our values and international law, but that we are seen to do so."

The foreign secretary is responsible for the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6 and GCHQ, which is the electronic "listening" agency.

He referred to the Gibson inquiry into the torture allegations - and recent Green Paper proposals to enable the greater use of secret intelligence material in court cases - as evidence of the government's commitment to act differently in future.

"We are confident that taken together these changes represent the most comprehensive effort yet to address the complex issues thrown up by the need to protect our security in the 21st Century and to do so in a way that upholds our values and begins to restore public confidence," Mr Hague said.

"So this will be our government's approach: drawing a line under the past, creating the right legislative framework so that the interests of national security and justice are reconciled, and drawing on the talents and capabilities of the intelligence agencies to support foreign policy and our national security."

Both the inquiry and the Green Paper have been criticised, with lawyers representing detainees who allege torture saying they will boycott the former because hearings will be largely secret.

Human rights groups have also attacked the court proposals, suggesting they will lead to greater secrecy in the justice system.

Foreign Secretary William Hague: "Torture is unacceptable in any circumstances"

However, Mr Hague insisted that the Green Paper would actually strengthen scrutiny of the agencies, for example, by beefing up the powers of the Commons Intelligence and Security Committee.

He also said the justice system was "not currently equipped to pass judgement in national security cases involving information so sensitive that it cannot be disclosed in a courtroom".

"This leaves the public with unanswered questions and the security and intelligence agencies unable to state their case and defend themselves."

Allowing the use of closed courts in "exceptional instances" would address that issue, he argued, adding: "It is surely fairer to ensure that sensitive material can be considered in court under these arrangements, than that it is excluded altogether."

'Most ingenious'

Mr Hague acknowledged that intelligence "throws up some of the most difficult ethical and legal questions that I encounter as foreign secretary".

He said that each year he saw hundreds of operational proposals from the agencies, not all of which he approves.

But he said the UK had "some of the most ingenious, resourceful and respected intelligence agencies in the world", without whom "terrorist groups would have free rein to harm UK citizens here and abroad".

"Properly used, secret intelligence saves both military and civilian lives, protects our economy, stops serious crime and makes a critical contribution to our diplomatic and military success.

"We use our intelligence agencies for specific needs which only they in government are equipped to address; such as countering particular forms of crime, terrorism or state espionage.

"They provide an early warning system against states which take actions which are hostile to us or to our interests."

- Published13 July 2011

- Published15 September 2010

- Published9 March 2011