Public sector strike: The start of a long struggle?

- Published

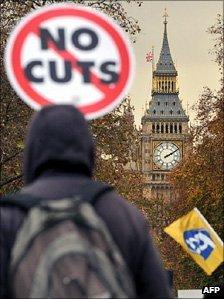

Spending cuts and falling incomes mean there may be more strife ahead

Was this strike a one-off or the start of a longer struggle?

Across the country there were padlocked playgrounds, demonstrations and widespread pickets.

Health workers, librarians, civil servants, road sweepers, customs officers and dinner ladies joined other public sector workers in the strike - the biggest for 30 years.

The TUC claimed two million union members stayed away from work in protest at the government's pension plans.

The government tried to talk down the disruption.

The chaos forecast for airports did not happen. Whitehall volunteers (including the prime minister's own press secretary) checked passports and kept the queues moving.

Number 10 claimed that just a quarter of civil servants joined the strike. Job centres stayed open, even though they do not have many jobs to give out.

Ministers had resigned themselves to this walkout weeks ago but again criticised the trade unions for jumping the gun and balloting members while talks were continuing.

At prime ministers' questions, David Cameron condemned the strike as "irresponsible" and insisted the latest pension offer was fair.

His exchange with Ed Miliband was one of the angriest they have had and sharpened the political definition between the two.

Labour has refused to support the strike (and the actions of its trade union affiliates) but has said its cause should be understood.

The strike has revived political rhetoric not heard in the Commons since the 1980s.

Mr Miliband said he would not "demonise" the low-paid cleaners and dinner ladies who had decided to strike. David Cameron called the Labour leader "irresponsible, left-wing and weak".

Huge risk

So what happens now? Top-level talks between union leaders and government negotiators have not happened since 2 November.

Some scheme-specific talks have continued during the month and there are people on both sides who say agreement is close.

But a sense that this dispute would be settled soon after the strike was over has faded.

On Wednesday, Education Secretary Michael Gove said trade union leaders including Mark Serwotka at the PCS and Unite's Len McCluskey had a "political agenda" and now wanted a militant struggle with the government.

The general secretary of the TUC Brendan Barber dismissed the charge as a caricature from the 1970s. But he said if agreement could not be reached, further action could follow.

It is a huge risk. In 1926, 1979 and 1984-5, mass strikes failed when the unions failed to keep the public on side.

The government has claimed its current offer is the best there will be and ministers want a deal by the end of the year.

Away from the crowds of demonstrators, banners, pickets and protests, a quiet basement room in London hosted a briefing for journalists.

Economists at the Institute for Fiscal Studies had crunched the chancellor's numbers and their verdict was bleak.

Britain is now in a "lost decade" of falling incomes and unprecedented spending cuts that will last for years.

The public sector faces further job losses and pegged-back pay. At some point this pensions dispute will end. But it may not be the end of the strife.