What is the role of bishops in UK politics?

- Published

The Bishop of Ripon and Leeds led peers opposing the government over welfare changes

A Church Of England bishop led this week's House of Lords defeat for the government over its plans to cap benefits given to families. But are clergymen an appropriate voice in Parliament for compassion and charity, or an anachronism with no right to override the opinions of elected MPs?

It was the bishops wot won it - sort of.

Five Lords Spiritual - some of the most senior figures in the Church of England - helped cause the government an embarrassing defeat on Monday.

They were led by the Bishop of Ripon and Leeds, the Right Reverend John Packer, who argued that plans to limit the amount of benefits a single household can receive "cannot be right".

By a margin of 15 votes - made possible by 26 Liberal Democrat peers rebelling - Parliament's Upper House backed an amendment to the Welfare Reform Bill excluding child benefit from the package.

The bishop and his supporters say this will ensure vulnerable young people do not suffer from spending cuts.

But ministers warn that it will render any benefit limits so high they are "pointless".

And the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Carey, has weighed in on the government's side, saying the Lords Spiritual "cannot lay claim to the moral high-ground" because the level of public debt was partially caused by the welfare bill.

A battle of wills between the Commons and Lords looks set to ensue, with the bishops at the heart of it.

'No restrictions'

But is it right that unelected men of England's established faith should seek to change the law?

A Church of England spokesman told the BBC: "Bishops are members of the House and have the same rights and entitlements and duties as the others.

"There are no restrictions placed on bishops in terms of how they participate, no bar on them getting involved in process."

He added: "If you look back through history, they haven't had a self-denying ordinance on important issues."

The Lords Spiritual - not affiliated to any political party - date back to the 14th Century and, apart from a few years after the English Civil War, have been ever-present in the chamber.

In 1847 their number was restricted to 26.

With 44 dioceses in the Church of England, this means that places are reserved for the archbishops of Canterbury and York, and the bishops Durham, London and Winchester.

The other 21 go to the remaining bishops who have served the longest time in office.

A "duty bishop" - worked out on a rota system - leads daily prayers in the chamber.

'Spiritual insight'

The Church of England's website says of the Lords Spiritual: "Like other members of the Lords, they do not represent a parliamentary constituency, although their work is often closely informed by their diocesan role."

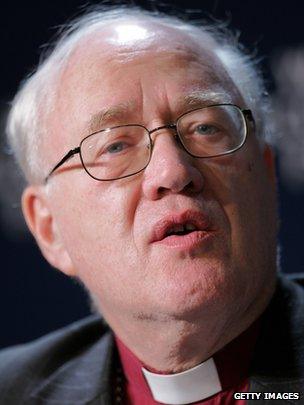

Lord Carey said the moral argument was in favour of the government's changes

It adds: "Their presence in the Lords is an extension of their general vocation as bishops to preach God's word and to lead people in prayer."

They "provide an important independent voice and spiritual insight to the work of the Upper House and, while they make no claims to direct representation, they seek to be a voice for all people of faith, not just Christians".

Some other faiths might disagree with the last point, while secular groups dislike the mingling of faith and politics.

And there are constitutional arguments against the Lords Spiritual, who leave the House when they retire, by the age of 70.

Some, like Lord Carey, are later given life peerages.

A spokesman for the group Unlock Democracy, which campaigns for political change, said: "People who sit in Parliament shouldn't be there as a result of holding another position.

"That particularly applies to religious groupings. But at least I can see the argument of why an expert in a subject should be there, rather than someone representing a religion."

Unlock Democracy argues that this merely exemplifies a cultural dominance of Anglicanism out of proportion to its true - rather than official - national role.

'Status'

The spokesman said: "There are also better ways of representing religion, ways that looks at a wider range of groups.

"I have some sympathy for the position the bishops are taking over benefits, but it isn't really worth all the extra status that they are given."

However, the Church of England says it is an advocate - not an opponent - of diversity.

A spokesman said: "We would quite like to see representatives from other faiths in the House. That's been part of our official position for at least a decade."

The bishops deny they represent a sort of "Christian party" in the Lords and Lord Carey's comments - so at odds with those of his former colleagues - are a reminder of this.

Elizabeth Hunter, of the religious think-tank Theos, thinks the benefits debate is a "difficult issue - morally and technically".

She said: "There's no settled Christian position. [Work and Pensions Secretary] Iain Duncan Smith is also a Christian and well known to be passionate about relieving poverty, but the bishops are motivated by what they feel is a special duty of their office to look to the wellbeing of the most vulnerable.

"They have a real pastoral duty in their parishes. There's legitimate disagreement, therefore, on achieving what everybody wants."

'Not beholden'

She added: "They haven't overstepped any mark, constitutionally speaking. The House of Lords is doing exactly what it should do: scrutinising legislation and encouraging the government to think again where necessary.

"There's no doubt that the cap is a popular measure, and the bishops' position wouldn't command broad support. But it is important that we have a House that's not so beholden to public opinion, so peers can do and say unpopular things."

What of the suggestion that they are more representative of localities across England than their fancily titled life and hereditary peer colleagues, who often have little connection with the places are which they are named?

An Unlock Democracy spokesman said: "It's certainly the case that they have their dioceses and, in that way, they represent their areas. I would agree that that's a desirable thing.

"In plans for an elected second chamber we are talking about some kind of constituency element, at a regional or lower level. But these have to be elected to be properly representative."

The government wants to cut the number of peers to 300, with most being elected and 12 or so Lords Spiritual remaining in place.

This - like welfare reform - is still up for debate.

The Lords Spiritual are involved in two of the most divisive subjects known to man: religion and politics.

The last week has not made their position any less controversial.

- Published25 January 2012

- Published24 January 2012