Nudge theory trials 'are working' say officials

- Published

Officials believe 'nudge theory" can help recover more tax

Trials suggest millions of pounds could be saved by using "nudge theory" about how people behave to encourage them to pay taxes and fines, officials say.

Trials organised by a special government unit suggest so-called "nudge theory" could play a "key role" in reducing fraud, error and debt.

Using simpler language in letters, highlighting key messages and stressing "social norms" have boosted compliance.

In one case, a local authority saved £240,000 on false council tax claims.

Nudge theory is seen as a way of producing positive economic and social outcomes without resorting to bans or increased regulation.

The Cabinet Office established a "behaviour insights team" after the 2010 general election and the unit has published details, external of some of the work it has been doing in the past eighteen months.

'Minor changes'

It says eight trials carried out in partnership with government departments and agencies have shown that "relatively minor changes to processes, forms and language can have a significant positive impact on behaviour".

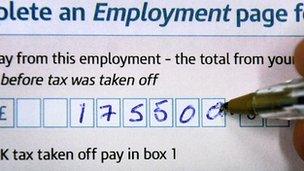

In one six-week exercise, 140,000 people were sent a variety of letters by Revenue and Customs.

One was a standard communication stressing the need to pay outstanding taxes while others contained statements such as "nine out of 10 people in Britain pay their tax on time" or stressed other people living in the same area had already complied.

Letters emphasising such "social norms" produced a 15% higher response rate than the standard letter. Revenue and Customs believe this could help it to collect £160m extra tax revenues a year if borne out across the country.

A new approach to collecting council tax could bring "significant savings" to town halls, the Cabinet Office report suggests.

In a trial conducted in November, Manchester City Council saved £240,000 by using a different tone in letters to people claiming a single person discount on their council tax bills.

While it previously just required people to fill out a form saying their circumstances had not changed, it is now asking them to state directly that they are still eligible.

This method - which also downplayed references to the size of the discount and warned that knowingly providing false information was an act of fraud - resulted in a 6% fall in people claiming the rebate.

The change of approach was based on the theory that people are less likely to lie if they are forced to "actively provide" false information rather than simply not updating their details.

'Different incentives'

In another trial, doctors and dentists with outstanding tax liabilities were told that their failure to pay in the past was regarded as an oversight but if they did not respond in future it would be seen as a conscious decision.

The letter - which also warned that third-party information could be used to prove they were defrauding the exchequer - resulted in a 14% higher response rate and prompted £1 million in voluntary disclosures.

Officials said other initiatives, such as sending personalised text messages urging people to pay fines and including images of untaxed vehicles in demands for payment of duties - had proved initially successful.

Other ideas worth considering in future, they added, included highlighting key information in bold or "strong" colours, using lotteries or prize draws as an incentive for prompt payment of taxes and sending "thank you" letters to people.

'Incentives'

The Cabinet Office said the trials showed the importance of "understanding better how people respond to different contexts and incentives" in framing communications.

"We are confident that results like these could be achieved across a range of areas by applying the insights set out. Indeed, if trialled on a national scale, we expect that these interventions will save hundreds of millions of pounds."

However, it stressed that not all approaches had worked - asking people to sign a letter at the start rather than the end did not increase responses - and methods used had to be properly tested and adapted.

Critics of nudge theory argue that it can only achieve limited goals.

The House of Lords science and technology committee said last year that plans to get people to adopt healthier lifestyles would not work unless the government is more prepared to use legislation.

And a senior official at the Department of Health said behavioural insights were not a "silver bullet" and it could take up to 40 years to tell whether they had had any impact on issues such as child obesity.

- Published19 July 2011

- Published9 November 2010

- Published15 September 2011