The truth behind UK migration figures

- Published

- comments

Ever wondered how many people are moving to, and leaving, the UK? If so, you're not the only one - the official figures are said by some experts to be based on not much more than guesswork.

Yes, despite few issues mattering more to politicians and the public than migration, the UK still does not have an accurate system for counting people in and out.

The e-borders scheme - which was meant to do this job - is still a work in progress, and despite government assurances to the contrary, there are some who fear it might stay that way.

Instead the government relies on the answers given by a sample of travellers who agree to be stopped and questioned by a team of social survey interviewers at Heathrow and other main air, sea and rail points of entry to the UK.

And despite the increasingly high hurdles to jump through to get a visa to come to the UK, it seems there is no way of knowing if someone is still in the country when it expires.

Keith Vaz, chairman of the influential home affairs committee says he finds it incredible that a supermarket loyalty scheme can collect and store details on the shopping habits of millions of people, yet a similar database can not be set up to record arrivals and departures.

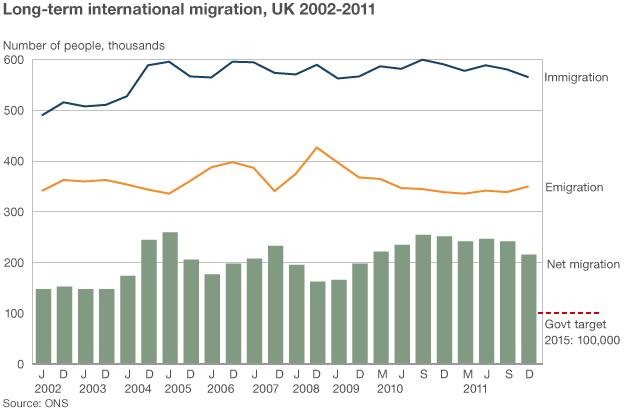

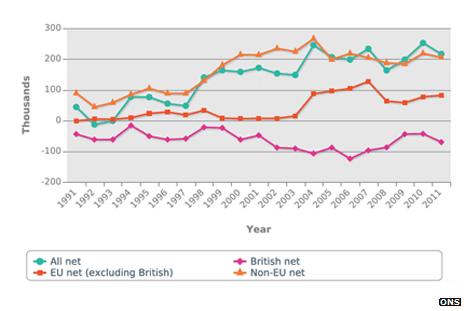

Particularly when the coalition government sets such store by reducing "net migration" - the difference between the number of people entering and leaving the country.

So if Britain does not count everybody in as they arrive, and count them out again as they depart, where exactly do the net migration figures announced each quarter by the government come from?

The main source is the International Passenger Survey (IPS), which was designed in the early 1960s to find out how much foreign tourists were spending in the UK - something it is still used for today.

It works something like this: There are about 240 IPS officials stationed at major airports and ports around the country.

They pick out every 10th, 20th or 30th passenger streaming through arrivals or departures, depending on how busy they are that day, and ask if they wouldn't mind taking part in a short survey.

"There may be times when, owing to a particular flood of passengers, you just cannot keep an accurate count. Do not panic if this happens but keep counting as best you can," advises the Office for National Statistics training manual.

'Hopelessly inadequate'

The ONS takes the raw IPS data and adds information about asylum seekers and migration statistics from Northern Ireland, as well as figures for people who have entered the country on short-term visas and decided to ask to extend their stay, before arriving at a final immigration figure.

About 300,000 people are interviewed each year by IPS officials - about 0.2% of the 200 million who enter and leave the UK over the same period.

The IPS has been considerably beefed up in the past three years, after it came in for stinging criticism from senior figures, including Bank of England governor Mervyn King, who branded it "hopelessly inadequate".

The ONS admits the survey is still not perfect but points out that 800,000 people are sampled to find the 300,000 interviewees and it has cast its net wider than Heathrow, where most interviewers were based, to other airports around the country and ferry terminals at Dover and Portsmouth it says 95% of travellers now "have a chance" of being interviewed.

It also has the virtue of being long established and relatively cheap.

But it is entirely voluntary and despite the training manual's advice to interviewers to be cheerful at all times - "no one wants to be interviewed by an unsmiling person with a dreary monotonous voice". Although the response rate is 78%, the ONS says that only 2% of people approached refuse to take part in it.

Passengers travelling at night, when interviews are suspended, or on smaller, low volume routes also slip through the net.

The one thing the IPS has over other sources of data on immigration - such as the number of non-EU passengers passing through border control, new NHS registrations or new National Insurance numbers - is that it records how long migrants say they intend to stay in the country.

How accurate are the official net migration figures?

But its major flaw, according to experts, is when it comes to measuring how many people are leaving the country.

IPS emigration estimates are based on interviews with just 2,000 people (who, the ONS point out, are found from interviews with about 400,000 interviews) - and there is currently no alternative source of data to measure them against.

This matters because the coalition government has promised to reduce net migration - the difference between those entering and leaving the country - to "tens of thousands" by 2015.

'Difficult'

Home Secretary Theresa May hailed "the first significant falls in net migration since the 1990s" in her keynote speech to the Conservative Party conference.

What she failed to mention was that when that "significant fall", from 252,000 to 216,000, was announced, the margin of error was also revealed for the first time.

This showed that the main source of these figures was only accurate to within plus or minus 35,000 people.

In other words, according to the ONS, the fall was not yet statistically significant.

This does not mean, of course, that net migration has not fallen, just that, according to some experts, the government's main method of measuring its progress is little better than a rough guess.

"It is very difficult to assess how well the government is progressing toward its target of reducing net-migration to the 'tens of thousands', or to evaluate the effects of specific policy changes," says Dr Martin Ruhs, Director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford.

"In simple terms the government could miss the 'tens of thousands' target by many tens of thousands and still appear to have hit it - conversely the government could hit, or even exceed its target and still appear to have missed it."

The government denies that the IPS is a faulty instrument for measuring its progress on migration.

In a statement to the BBC, Immigration Minister Mark Harper said: "The International Passenger Survey already provides the ONS with a reliable method of measuring net migration.

"By 2015, we aim to reintroduce exit checks using the e-borders system, which will allow us to build an even more accurate picture of the number of people entering and leaving the country."

A brainchild of the Tony Blair era, when it seemed as if there was no problem that could not be solved by a multi-billion pound IT project, e-borders was meant to replace the old paper-based embarkation system, which was scrapped in the 1990s.

Since then departures from the UK have not been officially recorded.

So it is possible for migrants to enter on short-term visas and - unless they notify the authorities of their intention to stay longer or are really, really unlucky and are picked up in a Border Force raid - stay in the UK or leave the country years later without showing up in the official records.

It was one of the justifications Mr Blair made - and is still making - for the introduction of an identity card system.

E-borders which was primarily meant to improve security, when combined with a biometric identity card scheme, began collecting details of passenger and crews for inbound flights from outside the EU at nine airports in March.

The plan now is to extend it to ports and railway stations by 2014 and to passengers from within the EU by 2015.

But that will depend on persuading all EU countries to share passenger and crew list information - quite a number of them regard this as illegal under European free movement laws.

High hopes

And there are some, such as Keith Vaz and Sir Andrew Green, of think tank Migration Watch, who fear the project, which was meant to be up and running in time for the Olympics, may have stalled altogether.

"The government will rightly be held to account if they fail to achieve a steady and substantial reduction in net migration, whatever the technical details," said Sir Andrew.

"But it is time we were told more about the purpose and progress of the e-borders programme."

The statisticians at the ONS still have high hopes that e-borders will one day be able to provide reliable migration statistics.

But they say it will be 2018 at the earliest before they can even start incorporating data from the programme into their estimates - and there are no plans to replace the IPS as the main source of migration data.

So until the Home Office can be persuaded to come up with a different method - the men and women of the IPS will continue to put on their best smiles and try not to panic as they scan the arrivals halls of Britain's ports and airports.

And net migration statistics should continue to be taken with a major dose of salt.

- Published16 July 2012

- Published5 July 2012

- Published30 August 2012

- Published6 September 2012

- Published21 September 2012

- Published17 September 2012