UK to end financial aid to India by 2015

- Published

- comments

International Development Secretary, Justine Greening: "India is very successfully developing as an economy"

The UK is to end financial aid to India by 2015, international development secretary Justine Greening has said, external.

Support worth about £200m ($319m) will be phased out between now and 2015 and the UK's focus will then shift to offering technical assistance.

Ms Greening said the move, which will be popular with Tory MPs, reflected India's economic progress and status.

Giving his reaction, India's foreign minister Salman Khurshid said: "Aid is the past and trade is the future."

But charities described the move as "premature" and warned it would be the poorest who suffered.

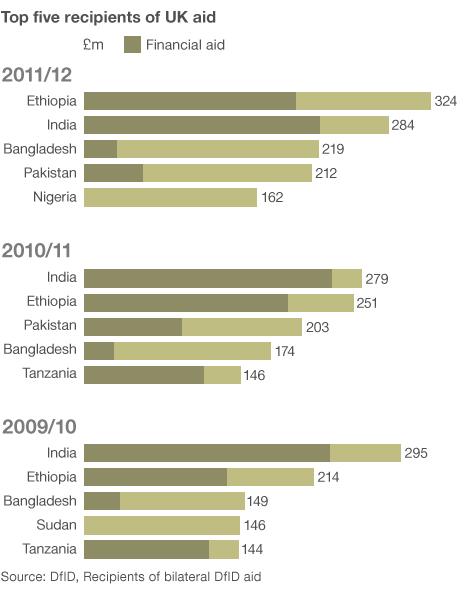

Until last year, when it was overtaken by Ethiopia, India was the biggest recipient of bilateral aid from the UK, receiving an average of £227m a year in direct financial support over the past three years.

But the UK's support for India, one of the world's fastest-growing economies, has been a cause of concern among Conservative MPs, many of whom believed that the UK should not be giving money to a country which has a multi-million pound space programme.

Ministers have defended the level of financial help in the past on the basis of the extreme poverty that remains in rural areas and historical colonial ties between the two countries.

Ms Greening has been conducting a review of all financial aid budgets since taking over the role in September and visited India earlier in the week to discuss existing arrangements.

'Changing place'

She said the visit confirmed the "tremendous progress" that India was making and reinforced her view that the basis of the UK's support needed to shift from direct aid to technical assistance in future.

"After reviewing the programme and holding discussions with the government of India, we agreed that now is the time to move to a relationship focusing on skillsharing rather than aid," she said.

"India is successfully developing and our own bilateral relationship has to keep up with 21st Century India.

"It is time to recognise India's changing place in the world."

Although all existing financial grants will be honoured, the UK will not sign off any new programmes from now on.

Last year the UK gave India about £250m in bilateral aid as well as £29m in technical co-operation.

By focusing post-2015 support on trade, skills and assisting private sector anti-poverty projects which can generate a return on investment, the UK estimates its overall contribution will be one-tenth of the current figure.

In making the decision, the UK is citing the progress India has made in tackling poverty in recent years. It says 60 million people have been lifted out of poverty as a result of the doubling of spending on health and education since 2006.

India spends £70bn on its social welfare budget, compared with £2.2bn on defence and £780m on space exploration.

'Premature'

From 2015, development experts will continue to work alongside the Foreign Office and UK Trade and Investment but focus on sharing advice on poverty reduction, private sector projects and global partnerships in food security, climate change and disease prevention.

Emma Seery, Oxfam: "A third of the world's poorest people live there [in India]"

Save the Children said it believed the decision to end financial aid was "premature".

"Despite India's impressive economic progress, 1.6 million children died in India last year - a quarter of all global child deaths," Kitty Arie, its director of advocacy, said.

"We agree that in the longer term, aid to India should be phased out as the country continues to develop, but we believe that the poorest children will need our ongoing help."

After 2015, the UK should also support Indian non-government organisations to tackle child mortality and improve health provision, it urged.

'Hitting the vulnerable'

Labour MP Keith Vaz, a former chair of the Indian-British parliamentary group, said the government needed to reassure its Indian counterpart that their bilateral relationship was still a priority.

"Although undoubtedly India has progressed in the past 20 years, there are still an estimated 360 million people surviving on less than 35 pence per day," he said.

"In withdrawing our aid to India, which will clearly only affect the most vulnerable, we need to see the minister's plan for how she will work with other organisations to make sure the gaps we are creating will be filled."

War on Want, which campaigns to end global poverty, said aid should not just stop because India had become a middle-income country.

Financial support needed to be "smarter" and geared towards supporting "progressive movements" capable of bringing about political change and tackling growing inequality, the pressure group said.

The UK government is increasing the overall overseas development budget to meet a longstanding international commitment to spend 0.7% of national income on aid.

At the same time, it wants to re-align its expenditure to focus on the poorest countries and those scarred by recent conflict.

- Published1 March 2011

- Published7 March 2012

- Published12 April 2011