Prime ministers' speeches on Europe

- Published

David Cameron is giving a speech on Wednesday outlining his plans for the UK's place in the European Union. How have some previous prime ministers addressed the issue, asks Justin Parkinson.

Winston Churchill, Zurich, 19 September 1946

Just over a year after losing the 1945 general election, the former Conservative prime minister, who was to regain office in 1951, turned his attention to conflict-ravaged Europe's future.

His speech, in Zurich University, Switzerland, called for the creation of a "kind of United States of Europe" to ensure "peace, safety and freedom".

Churchill said he envisaged a "sense of enlarged patriotism and common citizenship to the distracted peoples of this mighty continent".

The speech was recently cited in a video produced to mark the Nobel Peace Prize being awarded to the European Union.

But Churchill was not speaking about the EU's precursor, the European Economic Community, which was not established until 1957, although moves towards it were already afoot.

His address was in praise of the separate Council of Europe, which had been established earlier in 1949 in the Treaty of London. Its main role is to ensure that its 47 member states abide by the European Convention on Human Rights.

Churchill called for a "partnership" between France and Germany, with France regaining the "moral and cultural leadership of Europe". His aim appeared squarely to be ensuring peace among European nations.

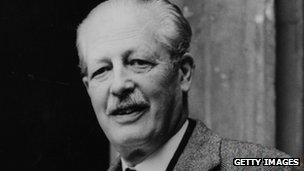

Harold Macmillan, House of Commons, 2 August 1961

The Conservative prime minister was pushing for the UK to join the European Economic Community, which had been established by "The Six" - Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands - in the Treaty of Rome four years earlier.

Macmillan was keen to strike an emollient tone with MPs. He stressed the use of the word "economic" in the EEC's title, adding that the founding Treaty of Rome "does not deal with defence" and "does not deal with foreign policy".

The prime minister appealed to practical, rather than "moral", considerations of membership, despite emphasising the recent "reconciliation of France and Germany" as a mark of it success.

Much of this could be explained by the "remarkable economic progress in recent years", he argued.

To counter fears that the UK's relationship with Commonwealth countries, which had done so much during the Second World War to help liberate Europe, would be weakened and damaged, Macmillan said that this and EEC membership would be "complementary".

He proclaimed: "I believe that our right place is in the vanguard of the movement towards the greater unity of the free world, and that we can lead better from within than outside. At any rate, I am persuaded that we ought to try."

Two years later, in 1963, French President Charles de Gaulle vetoed UK membership of the EEC. He did the same again in 1967.

Edward Heath, Brussels, 22 January 1972

Edward Heath had just realised his dream of getting the UK to join the European Economic Community. After signing the Treaty of Accession in Brussels, he said the ceremony marked "an end and a beginning" and demanded "clear thinking and a strong effort of the imagination".

In the short speech, the Conservative spoke of a "common European heritage", but added that he valued "national identity".

In contrast to Macmillan, with whom he had worked closely as a cabinet minister, he did not describe the Commonwealth and the EEC as being separate but complementary.

Rather, Heath suggested that the UK's leading role in a major international grouping provided the experience to "contribute to the universal nature of Europe's responsibilities".

Looking ahead, he predicted that the EEC could help improve relations with countries under the control of the Soviet Union.

Heath praised the founders of the EEC for their "originality" in devising collective institutions, but warned: "It is too early to say how far they will meet the needs of the enlarged community."

Margaret Thatcher, Bruges, 20 September 1988

The Conservative prime minister's famous critique of the European Economic Community emphasised a vision of Europe working to help its member states, rather than the other way around. The EEC was "not an end in itself" and power should not be concentrated in Brussels, at the expense of nationhood.

Thatcher warned an audience at the College of Europe, in the Belgian city of Bruges, against creating an "identikit European personality".

Unlike Heath - who saw the EEC as a bulwark against communism and a possible source of weakening Moscow's influence - Thatcher likened its role to that of the Soviet Union, as a force for centralisation and excessive state control.

"We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels," she exclaimed.

Thatcher also argued against the idea that Europe's economic prosperity, facilitated by free markets and integration, had been the major reason for peace since the war. She credited Nato for this instead. Thatcher urged Nato's member states to "strive to maintain" the US's commitment to ensuring transatlantic defence against common enemies.

She urged EEC states not to give up border controls, to prevent the spread of terrorism, drugs, crime and illegal migration.

The overall effect of the "Bruges speech", often cited today by those who want the UK to withdraw from the EU, was to push to re-establish the idea of a free trade, rather than a political, alliance.

Yet Thatcher was at pains to demand a reappraisal of the relationship, rather than a severance, stating: "Britain does not dream of some cosy, isolated existence on the fringes of the European Community. Our destiny is in Europe, as part of the Community."

John Major, London, 15 April 1991

At the end of a long speech outlining his political beliefs to the Conservative Central Council, Major, who had been prime minister for four months, said: "It is because we care for lasting principles that I want to place Britain at the heart of Europe."

In an effort to assuage Eurosceptics, he added that "partnership in Europe will never mean passive acceptance of all that is put to us". He reassured his audience that the UK would maintain its national identity and would be able to "inspire and shape" the European project.

Major promised to "fight" for change "from the inside, where we will win".

His detractors accused him of being over-compliant with Brussels - even of voicing proto-federalist ideas, which he and his advisers fiercely denied. The speech came a few months before the Maastricht summit, at which the creation of the European Union was agreed. Tensions were high.

The EEC became the European Union at the beginning of 1993. In another speech, to the Conservative Group for Europe in April that year, Major explicitly contradicted Thatcher's point about Nato being the true cause of peace in Europe, saying the EEC and EU had brought "this gift to our age".

His rhetoric also became less placatory: "Many who fear and oppose Europe are like the fat boy in 'Pickwick'. They want to make your flesh creep. They think we are always going to lose the argument in Europe. That is defeatist and wrong. We learnt to swim in that sea long ago."

The issue of Europe, including the Conservative Party's internal arguments over the ratification of Maastricht, dogged Major's premiership until he lost power in 1997.

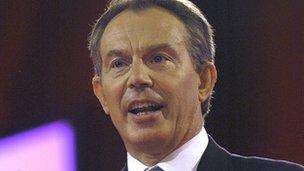

Tony Blair, Brussels, 23 June 2005

Shortly after the UK took on the six-month presidency of the European Union, the Labour prime minister addressed Members of the European Parliament.

The speech also followed the rejection of the European Constitution - proposing a full-time president of the European Council and a common defence policy - by voters in France and the Netherlands.

Blair's tone was distinctly different to Thatcher's and Macmillan's in stressing the explicit "political project" of the European Union.

He said: "This is a union of values, of solidarity between nations and people, of not just a common market in which we trade but a common political space in which we live as citizens."

He described the EU as vital in dealing with growing "globalisation", saying the group had to "modernise" by focusing less on farm subsidies and enlarge its membership to include more former Eastern Bloc countries.

Blair also advocated the "social model" for the EU. This meant investing more in job creation and a knowledge-based economy.

"It's time to give ourselves a reality check, to receive a wake-up call," he said.

Five years earlier, in February 2000, Blair voiced his unhappiness with the sentiments expressed by Thatcher, saying: "My disagreement is that the response to those criticisms was for Britain to withdraw into its shell, to opt out.

"We should be leading the way in Europe, shaping the direction of Europe, participating in debates and working in partnership with the others for a more prosperous economy for our people."

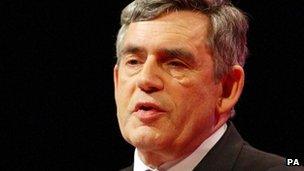

Gordon Brown, London, 14 January 2008

After the European Constitution was discarded, its successor - the Treaty of Lisbon - was in the process of being ratified by member states when Labour's Gordon Brown gave a speech to UK business leaders. It also came in the context of the global economic crisis which had begun a few months earlier.

The prime minister repeated Blair's argument that the EU would help deal with the challenges of globalisation, by focusing on promoting "its skills, its innovation and its creative talents".

He added: "In this way the enlarged Europe moves forward from its original objective of preserving the peace to its future achievement - widening and deepening opportunity and prosperity not just for some but for all."

Brown stressed the EU's role in ensuring free trade among its members, as an antidote to protectionism and economic decline.

He called for a "more competitive" Europe, which must "face outwards if it is to be open for business".